По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

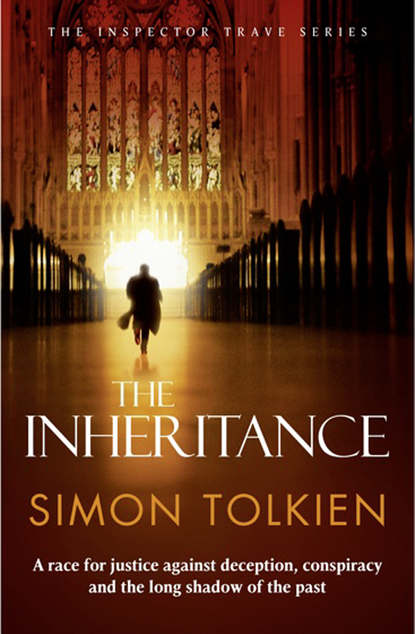

The Inheritance

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Well, for a start, we can’t explain how he could’ve entered the house. He can’t have come through the gate because you closed it on him when you went up there before seeing your father, and any other route of entry is scotched by this damn security system. I’m sorry to have to tell you all this, Stephen, but it’s no use denying facts. I know you think everything’s related to the blackmail letter and what happened in France fifteen years ago. But it’s all just too tenuous. We did what you asked us to. I sent an investigator over to Rouen, and the records office told him there were no close living relatives of the murdered family or their servants.’

‘Maybe he didn’t look hard enough?’

‘No, he did. I promise you he did. He went to Marjean as well, but the place is a ruin and everyone in the village said the same thing: no survivors. Same with the local police.’

‘Why couldn’t you go yourself?’

‘Because that’s not what I do,’ said Swift, trying to keep the exasperation out of his voice. ‘I’m in court almost every day, and I can’t do two different jobs even if I wanted to. The man we sent is one of the best. You can take my word for it.’

‘But didn’t you tell me before that some of the records got destroyed when the Germans invaded?’ asked Stephen, unwilling to leave the subject.

‘Only for the two years up to 1940, which aren’t relevant. The rest were in secure archives. Monsieur Rocard was an only child. His wife was from Marseille and had a couple of brothers, but they were killed in the war. They married late and didn’t have any children. End of story. We did what you asked us to do, and it’s not really taken us anywhere, Stephen. We need something more than that your father had a murky past.’

‘Like what?’

‘Like an alternative suspect to you. Somebody real. Somebody the jury can believe in. Not some phantom foreigner who’s run away from a speeding ticket.’

‘Well, there isn’t anybody else,’ said Stephen.

‘Yes, there is. Your brother Silas had just as much of a motive to kill your father as you did. You heard what the solicitor said. He was going to be disinherited too.’

‘No,’ insisted Stephen, suddenly angry again. ‘My brother wouldn’t kill anyone. He always got on better with our father than I did, for God’s sake.’

‘Perhaps he was better at concealing his true feelings than you were.’

‘No. I know him.’

‘Do you, Stephen? How can you be so sure? He’s not your blood brother, is he?’

Stephen’s brow was creased with thought but he didn’t respond, and after a moment Swift got up, noticing the gaoler waiting impatiently outside the glass door of the interview room. Then, as Stephen was being handcuffed, Swift made one last effort to get through to his client. ‘Silas will be in the witness box the day after tomorrow, Stephen. If I’m to help you, I need you to help me.’

But Stephen didn’t reply. Instead he turned away from his barrister and allowed himself to be led away down the whitewashed corridor and out of sight.

Swift climbed up the stairs from the cells and found Stephen’s girlfriend, Mary, waiting for him in the foyer of the courthouse. She was clearly agitated, and her cheeks were flushed. It made her seem even prettier than he remembered.

‘Have you seen him?’ she asked.

‘Yes. Just now. Down in the cells.’

‘How is he?’

‘All right. I’d say he’s bearing up pretty well, all things considered. There’s a long way to go yet.’

‘He’s going to get off, isn’t he?’ she asked. ‘He’s going to be all right.’

‘I certainly hope so,’ said Swift, inserting a note of optimism into his voice that he was far from feeling. His interview with Stephen in the cells had left him more downcast about the case than ever before. He smiled and turned to go, but Mary put her hand on his arm to detain him.

‘You don’t understand,’ she said. ‘I need to know. What are his chances?’

Swift paused, uncertain how to answer the girl. Was she looking for reassurance or an assessment of the evidence? Catching her eye, he decided the latter was more likely.

‘It’s an uphill struggle,’ he said. ‘It would help if there was somebody else in the frame.’

Mary nodded, pursing her lips.

‘Thank you, Mr Swift,’ she said. ‘That’s what I thought.’

CHAPTER 4

Moreton Manor in the morning was a pleasing sight. The dappled early autumn sunlight glistened on the dew covering the newly mown lawns and sparkled in the tall white-framed sash windows that ran in lines around the manor’s classical grey stone façade, which rose in elegant symmetry above the ebony-black front door to a slanting, tiled roof surmounted by tall brick chimneys. A single plume of white smoke was rising into a blue, cloudless sky, but otherwise there was no sign of life apart from a stray squirrel running in unexplained alarm across the Tarmac drive, which cut the lawns in half on its way down to the front gate. An ornamental fountain in the shape of an acanthus plant stood in the centre of the courtyard, but it was a long time since water had flowed down through its basin. The professor had found the sound of the fountain an unwanted distraction from his studies, and without it the silence in the courtyard seemed somehow solemn, almost oppressive.

Trave stood lost in thought, gazing up at the house. He’d been awake since before the dawn, restless and unable to sleep. He kept on turning over the events of the previous day in his mind: Stephen in his black suit looking half-ready for the undertakers; old Murdoch, angry and clever up on his dais; and the barristers in their wigs and gowns reducing a murder, the end of a man’s life, to a series of questions and answers, making the events fit a pattern neatly packaged for the waiting jury. But it was all too abstract: a post-mortem without a body. There was something missing. There had to be. Trave knew it in his bones.

And so he’d driven out to Moreton in the early light and now stood on the step outside the front door, hat in hand, waiting. It was Silas who answered, and once again Trave was struck by the contrast between Stephen and his brother. Silas was just too tall, just too thin. His sandy hair was too sparse and his long nose spoilt his pale face. But it wasn’t his physical appearance that predisposed Trave against the elder brother; it was the lack of expression in the young man’s face and his obvious aversion to eye contact that struck Trave as all wrong. Silas was concealing something. Trave was sure of it. God knows, he had as much motive for the murder as his brother. They were both going to be disinherited. But then Silas wasn’t the one in his father’s room with the gun. That was Stephen, the one who reminded Trave so forcibly of his own dead son.

‘Hello, Inspector. It’s a bit early, isn’t it?’ There was no note of welcome in the young man’s flat, expressionless voice.

‘Yes, I’m sorry, Mr Cade. I was just passing. On my way to London for the trial.’

Silas’s eyebrows went up, and Trave cursed himself for not thinking of a better excuse.

‘I just wanted to check a couple of things if it’s not inconvenient,’ he finished lamely.

‘Where?’ asked Silas.

‘Where what?’

‘Where do you want to check them?’

‘Oh, I’m sorry. In the study, the room where your father died.’

‘I know where my father died,’ said Silas, opening the door just enough to allow the policeman to pass by him and come inside.

The room was just the same as Trave had described it in court the day before. And yet there was something else, something he was missing. His eyes swept over the familiar objects: the ornate chess pieces on the table, the armchairs and the desk, the thick floor-length curtains. And now Silas, standing and watching him by the door, the door his brother had unlocked on the night of the murder.

‘Did you like your father?’ Trave asked, catching the young man’s eye for the first time.

‘No, not particularly. I loved him. It’s not the same thing.’

‘And what about your brother? How do you feel about him?’

‘I feel sorry for him. I wish he hadn’t killed my father.’

‘Your father?’

‘Our father. What difference does it make? What’s done is done.’

‘And now someone has to pay for it.’