По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

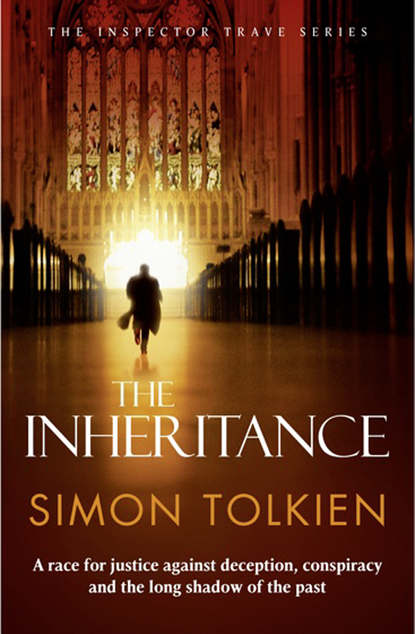

The Inheritance

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The Inheritance

Simon Tolkien

When an eminent art historian is found dead in his study, all the evidence points to his estranged son, Stephen. With his fingerprints on the murder weapon, Stephen’s guilt seems undeniable.As the police begin to question five other people who were in the house at the time, it is revealed that Stephen’s father was involved at the end of World War II in a deadly hunt for a priceless relic in northern France, and the case begins to unravel.As Stephen’s trial unfolds at the Old Bailey, Inspector Trave of the Oxford police decides he must go to France and find out what really happened in 1944. What artefact could be so valuable it would be worth killing for? But Trave has very little time – the race is on to save Stephen from the gallows.

SIMON TOLKIEN

The Inheritance

For my mother, Faith Tolkien

Table of Contents

Title Page (#ue67090c1-be8f-5103-b321-d840a0b0ff33)

Dedication (#ud84e509b-9bd8-5db9-9e0a-d1908f218894)

Introductory Note (#u20d02b94-4852-58ff-8611-0a6474a89b44)

Prologue: Normandy 1944 (#uf4dcabd8-76c1-5786-827d-76b195a16996)

Part One: 1959 (#u43c43a05-fca1-5058-9cd5-8d36d3102fc9)

Chapter 1 (#u49392414-234e-53a4-a2eb-d4117f675c9b)

Chapter 2 (#u17135194-6c3f-59d0-9974-6b090d7662b3)

Chapter 3 (#ua3af3623-dadc-575d-ba50-51987b902333)

Chapter 4 (#u3a46043b-d5a1-52ce-af22-691ac9db459e)

Chapter 5 (#u32835063-7cb5-531c-8551-50516ceebac6)

Chapter 6 (#u751f91f2-8ee2-561e-9937-c5296c9eeced)

Chapter 7 (#uf7eb23ed-6ce8-59c4-8aa6-bce7ed02cdb8)

Chapter 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Simon Tolkien (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

INTRODUCTORY NOTE

The controversial executions of Derek Bentley and Ruth Ellis in the 1950s increased public pressure in the United Kingdom for the abolition of hanging, and this was answered in part by the passing of the Homicide Act in 1957, which limited the imposition of the death penalty to five specific categories of murder. Henceforward only those convicted of killing police officers or prison guards and those who had committed a murder by shooting or in the furtherance of theft or when resisting arrest could suffer the ultimate punishment. The effect of this unsatisfactory legislation was that a poisoner or strangler acting with premeditation would escape the rope, whereas a man who shot another in a fit of rage might not. This anomaly no doubt helped the campaign for outright abolition, which finally reached fruition with the passage of the Murder (Abolition of Death Penalty) Act in 1965.

Death sentences were carried out far more quickly in England in the 1950s than they are in the United States today. A single appeal against the conviction but not the sentence was allowed, and, if it failed, the Home Secretary made a final decision on whether to exercise the royal prerogative of mercy on behalf of the Queen, marking the file ‘the law must take its course’ if there were to be no reprieve. There was often no more than a month’s interval between conviction and execution. Ruth Ellis, for example, spent just three weeks and three days in the condemned cell at Holloway Prison in 1955 before she was hanged by Albert Pierrepoint for the crime of shooting her boyfriend.

Simon Tolkien

When an eminent art historian is found dead in his study, all the evidence points to his estranged son, Stephen. With his fingerprints on the murder weapon, Stephen’s guilt seems undeniable.As the police begin to question five other people who were in the house at the time, it is revealed that Stephen’s father was involved at the end of World War II in a deadly hunt for a priceless relic in northern France, and the case begins to unravel.As Stephen’s trial unfolds at the Old Bailey, Inspector Trave of the Oxford police decides he must go to France and find out what really happened in 1944. What artefact could be so valuable it would be worth killing for? But Trave has very little time – the race is on to save Stephen from the gallows.

SIMON TOLKIEN

The Inheritance

For my mother, Faith Tolkien

Table of Contents

Title Page (#ue67090c1-be8f-5103-b321-d840a0b0ff33)

Dedication (#ud84e509b-9bd8-5db9-9e0a-d1908f218894)

Introductory Note (#u20d02b94-4852-58ff-8611-0a6474a89b44)

Prologue: Normandy 1944 (#uf4dcabd8-76c1-5786-827d-76b195a16996)

Part One: 1959 (#u43c43a05-fca1-5058-9cd5-8d36d3102fc9)

Chapter 1 (#u49392414-234e-53a4-a2eb-d4117f675c9b)

Chapter 2 (#u17135194-6c3f-59d0-9974-6b090d7662b3)

Chapter 3 (#ua3af3623-dadc-575d-ba50-51987b902333)

Chapter 4 (#u3a46043b-d5a1-52ce-af22-691ac9db459e)

Chapter 5 (#u32835063-7cb5-531c-8551-50516ceebac6)

Chapter 6 (#u751f91f2-8ee2-561e-9937-c5296c9eeced)

Chapter 7 (#uf7eb23ed-6ce8-59c4-8aa6-bce7ed02cdb8)

Chapter 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Simon Tolkien (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

INTRODUCTORY NOTE

The controversial executions of Derek Bentley and Ruth Ellis in the 1950s increased public pressure in the United Kingdom for the abolition of hanging, and this was answered in part by the passing of the Homicide Act in 1957, which limited the imposition of the death penalty to five specific categories of murder. Henceforward only those convicted of killing police officers or prison guards and those who had committed a murder by shooting or in the furtherance of theft or when resisting arrest could suffer the ultimate punishment. The effect of this unsatisfactory legislation was that a poisoner or strangler acting with premeditation would escape the rope, whereas a man who shot another in a fit of rage might not. This anomaly no doubt helped the campaign for outright abolition, which finally reached fruition with the passage of the Murder (Abolition of Death Penalty) Act in 1965.

Death sentences were carried out far more quickly in England in the 1950s than they are in the United States today. A single appeal against the conviction but not the sentence was allowed, and, if it failed, the Home Secretary made a final decision on whether to exercise the royal prerogative of mercy on behalf of the Queen, marking the file ‘the law must take its course’ if there were to be no reprieve. There was often no more than a month’s interval between conviction and execution. Ruth Ellis, for example, spent just three weeks and three days in the condemned cell at Holloway Prison in 1955 before she was hanged by Albert Pierrepoint for the crime of shooting her boyfriend.