По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

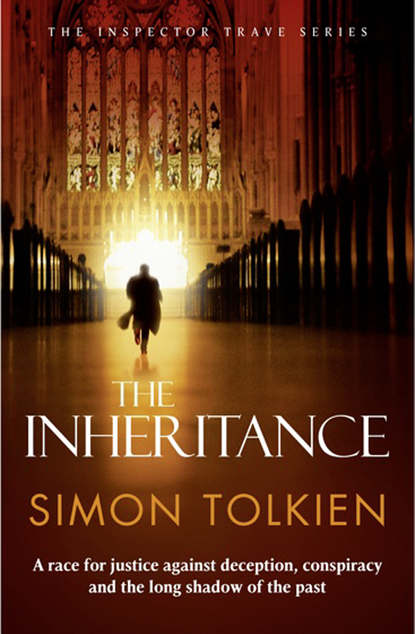

The Inheritance

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘That’s up to you. It’s your house. Perhaps you don’t want me there any more either.’

‘No, I do. Really I do.’

Silas cursed himself for raising the possibility of Sasha’s departure, and he turned round towards her to add emphasis to his words, taking his eye off the road as he did so.

‘Look out,’ Sasha shouted, and Silas was only just in time to slam his foot down on the brake and bring the car to a shuddering halt, inches away from an old woman crossing the road in front of them. His arm shot out across Sasha to prevent her being thrown forward, and he felt her breast against his hand for a moment, before she pushed him away.

‘You’re an idiot, Silas,’ she said angrily. ‘You could have killed that old woman, and us too.’

Silas said nothing. Instead he bent down to help Sasha, who was busy picking up the papers and books that had fallen out of her bag onto the floor. There was one yellowed document that caught his attention. It was covered with a spidery handwriting that Silas didn’t recognize. He noticed the date 1936 in the top corner and a name, John of Rome. It seemed to be a translation of some kind, but Silas had no chance to read any more before Sasha snatched the paper out of his hand.

‘Its part of our work on the catalogue,’ she said, even though Silas had not asked for any explanation. ‘Your father would have wanted me to finish it.’

They drove on into Oxford in silence, passing Silas’s little photographic shop and studio on the Cowley Road. He had spent hardly any time there since the murder, and he made a mental note to give the landlord notice at the end of the month. His inheritance at least meant that he wouldn’t need to earn his living as a humble portrait photographer any longer.

Sasha got out of the car almost without warning at a traffic light in Holywell and hurried away down a side street, clutching her shoulder bag tight to her side. Silas pulled over, half onto the pavement, and left the car unlocked as he ran after her. But she was already out of sight by the time he got to the first corner, and after a minute or two he gave up looking for her and went home.

CHAPTER 5

Sasha stepped out from behind the back gate of New College and looked around. Silas was nowhere in sight. She’d known instinctively that he’d try to follow her, although she still couldn’t understand his apparent infatuation. It repelled her, and she wished she could leave the manor house and never see its new owner again. Perhaps she should. In truth she was close to giving up on finding the codex. In the last five months, she’d turned the leaves of every manuscript that John Cade owned, but nothing had fallen out. She’d stared into every recess, tapped every wall, and found nothing – only the diary secreted in the hollow base of the study bookcase that she’d discovered two days ago.

Sasha held the book close to her as she hurried through a network of narrow cobbled lanes, turning left and right, apparently at random. She remembered her excitement when she first found it. The study had been dark apart from her torch, and for a moment she felt as if Cade was there, watching her from the armchair where he used to sit, slowly rotating his thick tongue around his thin lips as he turned vellum pages one by one. Sasha had never been a superstitious person, but still she’d shivered and hurried away with the book to study it in the privacy of her room. Pausing for a moment to take a key out of her pocket, Sasha remembered the disappointment she’d felt as the first grey light had filtered through her window and she’d realized that the diary had taken her no nearer to the object of her search. She felt certain now that the old bastard had had the codex, but she still had no idea where it was. It was a secret that he’d taken with him to the grave. Unless her father could help. He was her last chance.

Sasha had stopped outside a tall old house that had clearly seen better days. The paint was cracked and dirty, and a row of bells by the door pointed to multiple occupation. But she didn’t press any of them. Instead she used her key to unlock the door, and then climbed four flights of a steep, uncarpeted staircase to the very top of the house, knocked lightly, and went in.

A white-haired man in a threadbare cardigan sat in the very middle of a battered leather sofa in the centre of the room. He looked at least ten years older than his real age of sixty-seven. His whole body was painfully thin, his face was deeply lined, and he sat very still except for the hands that trembled constantly in his lap. In the corner, a violin concerto that Sasha didn’t recognize was playing on a gramophone balanced precariously on two towers of books. Everywhere in the room were similar piles, and Sasha had to navigate a careful path between them to reach her father. She arrived just in time to stop his getting to his feet. Instead, she kissed him awkwardly on the crown of his head and then went over to a rudimentary kitchen area beside the single dirty window and began making tea.

‘How have you been?’ she asked.

‘Not bad,’ said the old man just like he always did, speaking in the hoarse whisper that represented all that was left of his voice after the throat cancer he had fought off three years before. Now it was Parkinson’s disease that he was up against, and Sasha wondered how long his ravaged frame would hold out. She loved her father and constantly wished that he would allow her to do more, but he was obstinate, holding on fiercely to what was left of his independence.

‘You’ve brought something,’ he said, looking down at the bag that Sasha had left on the sofa.

‘Yes, it’s Cade’s diary. I found it hidden in his study. It’s only for five years though. From 1935 through to 1940. Nothing after that. I don’t know whether he stopped writing it or whether the next one’s hidden somewhere else.’

‘It was the war,’ said the old man. ‘Professor Cade became Colonel Cade, remember? No more time for autobiography.’

‘You’re probably right. The book’s pretty interesting, though. Except that there’s nothing in it about what he did to you. Look, here.’ Sasha opened the book and pointed to a series of entries dating from late 1937. ‘Anyone reading this would think that he won that professorship on merit. It’s vile. He called himself a historian, and yet he spent his whole life falsifying history. He knew you were going to win, and so he fabricated that story about you and that student.’

‘Higgins. He wasn’t very attractive.’ Andrew Blayne smiled, trying to defuse his daughter’s anger.

‘I thought I could get you back your good name.’

‘I know you did. But it doesn’t matter now. It’s all ancient history.’

‘It matters to me.’ Sasha’s voice rose as her old sense of outrage took over. She felt her father’s humiliation like it had happened only yesterday. Cade had persuaded one of his rival’s pupils to allege a homosexual relationship and the mud had stuck. Andrew Blayne had lost the contest for the chair in medieval art history and had then been forced by his college to resign his fellowship. Since then he had supported himself through poorly paid private tutoring and temporary lecturing jobs at provincial universities, until ill health had put a stop even to that.

His wife, Sasha’s mother, was a strict Roman Catholic and had chosen to believe every one of the scurrilous allegations against her husband. She’d left him in his hour of need, taking their five-year-old daughter with her, and had then stopped the girl from seeing her father for most of her childhood. Sasha had always found this cruelty harder to forgive than all her mother’s neglect, and Andrew Blayne had remained the most important man in his daughter’s life.

‘Clearing my name wasn’t the main reason why you ignored all my objections and went to work for that man, was it, Sasha?’ said Andrew reflectively, as he stirred the tea in his chipped mug. He noticed how Sasha had filled it only halfway to the top to avoid the risk of his spilling hot tea on his trousers. It suddenly made him feel like an old man.

‘You wanted to find the Marjean codex. Just like I did years ago. Because you thought it would lead you to St Peter’s cross,’ he went on when she did not answer. ‘You should be careful, my dear. You’re not the first to have followed that trail. Look what happened to John Cade.’

‘That’s got nothing to do with the codex,’ said Sasha, sounding almost annoyed. ‘Cade’s son killed him. He’s on trial at the Old Bailey right now, and I’ve got to give evidence next week. Don’t you ever read the newspapers?’

‘Not if I can avoid it. And plenty of innocent people get put on trial for crimes they didn’t commit, Sasha. They get convicted too.’

‘Not this one. The evidence is overwhelming. But look, I didn’t come here to talk about Stephen Cade’s trial.’

‘You came here to talk about the codex.’

‘Yes.’ Sasha’s voice was suddenly flat, full of her disappointment over all her fruitless searches of the last few weeks.

‘I’ll tell you again. I think you should leave it alone.’

‘I can’t.’

‘Why not?’

‘Because the codex, the cross – they should be yours. He stole everything from you.’

‘No, he didn’t, Sasha. I could have looked for the cross if I’d wanted to, but I didn’t. I chose not to.’

‘With no money?’ said Sasha passionately. ‘What could you do after he’d taken your livelihood away?’

The old man didn’t answer. He looked up at his daughter and smiled, before using both hands to contrive a sip of tea from his mug. But Sasha wouldn’t let it go.

‘I want to make it all up to you, Dad. Can’t you see that?’

‘I know you do, Sasha. But can’t you see that I don’t need objects? They mean nothing to me any more.’

‘I don’t believe you. Not this object.’

Not for the first time her father’s quiet stoicism grated on Sasha. It was beyond her comprehension that he could be so indifferent to what had been taken from him. Did he know more than he was saying? about Cade’s death? about the codex? and the cross? Suspicion creased her brow.

‘Look, I can’t even hold a cup of tea properly in my hand,’ said Blayne, gesturing with his shaking hand.

‘I know,’ she said. ‘I know.’ She felt foolish for a moment, ashamed of herself, looking down at her father’s ravaged body. She felt as if her long, fruitless search for codex and cross had started to make her see shadows in even the brightest corners.

‘I just want to have you and for you to be happy. That’s all,’ said Blayne.

It was hard to resist the appeal in his quavering voice or the tears glistening in his eyes, but Sasha’s face hardened, and she turned away from her father. Her jaw was set, and her lips folded in on themselves. She looked almost ugly.

‘I have to find it,’ she said quietly. ‘I’ve gone too far to stop now.’

Father and daughter looked deep into each other’s eyes for a moment before Andrew Blayne let go of Sasha’s sleeve and allowed his head to fall back against the sofa. He seemed to concentrate all his attention on a stain on the corner of the ceiling, and he kept his gaze fixed there even when he started speaking again.

‘Perhaps you’re wasting your time,’ he said. ‘Perhaps Cade never even had the codex.’