По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

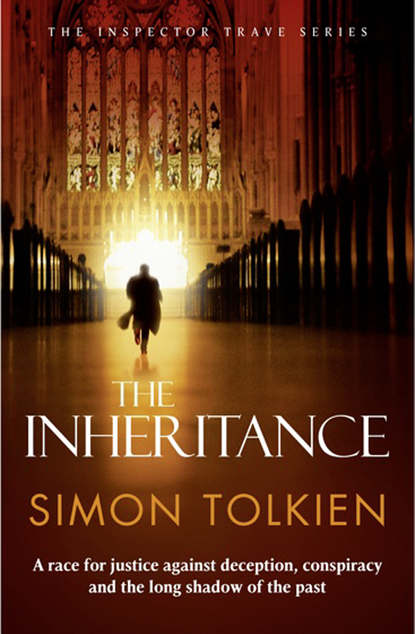

The Inheritance

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘But I know he did,’ said Sasha passionately. ‘That’s why this diary is so important. Look, let me show it to you. You remember that he supposedly hired me to help him with research for his book on illuminated manuscripts?’

‘The magnum opus.’

‘Exactly. But he didn’t really care about that at all. He was obsessed with St Peter’s cross. He kept sending me to this library and that, looking for clues. But it was a wild-goose chase, and I think he half-knew that deep down. He was like a man who’s followed a trail to its logical end and found nothing there. He goes back, taking every side turn that he passed before but without any faith that they’ll lead anywhere.’

‘And he needed you because he couldn’t do his own research. Because he wouldn’t go out.’

‘Yes, he was always frightened,’ said Sasha. ‘But the interesting part was that he was always looking for the cross in any place except the one where it ought to be.’

‘In Marjean?’

‘Yes. It was like he already knew it wasn’t there. I tested him once. I showed him the John of Rome letter. It was a risk that he’d connect me with you, but I don’t think he did. I said that I’d found a copy in the Bodleian Library. But he wasn’t interested. He said it was a false trail. A waste of time.’

‘I remember you telling me that,’ said the old man, becoming increasingly interested in spite of himself. ‘I was the one who showed him the letter back in 1936 when I thought we were friends. He pretended not to be interested then too.’

‘Except that he was,’ said Sasha excitedly, pointing to an entry in the diary. ‘Here it is. 13 May, 1936. He’s copied out the whole of your translation, word for word.’ Sasha held up the yellowed document covered with spidery blue handwriting that she’d snatched from Silas in the car. ‘Here’s your copy and that’s his. They’re the same.’

Blayne took the manuscript in his trembling hand and began to read it aloud. The hoarseness seemed to go out of his voice, and Sasha felt herself transported back five hundred years, out of her father’s disordered attic room in Oxford to a wood-panelled library in the Vatican.

Another old man in a black monk’s habit was writing a letter, dipping his quill in the inkwell at the top of his sloping mahogany desk. The sunshine sparkled on the Tiber and illuminated the parchment across which his old bony hand was moving steadily from side to side.

My dear brother in Christ,

Let me tell you then what I know of the cross of Saint Peter. It has long been lost, but is perhaps not destroyed. Perhaps you will one day see what I have never found.

Certain it is that the cross was made from a fragment of the true cross on which Our Lord suffered. Blessed Saint Peter, our first Holy Father, wore it when he took ship and crossed the great sea to spread the word of God. And he gave it to Tiberius Maximus, a citizen of this town and a good Christian before he, Peter, suffered death at the hands of the unbelievers. The people of God kept the holy relic safe through centuries of war and persecution, until it passed out of recorded history at the time of the invasions from the North, when this holy city was sacked by the barbarians.

Yet I have long believed that the cross survived and that it is the same as the famous jewelled cross that the great king Charlemagne kept in his royal chapel at Aachen in the eighth century. Many years ago I was working in the French king’s library in the city of Paris when I came upon an inventory of Charlemagne’s treasury made by a Frankish scribe. I attach a copy, and you will see that he speaks of the cross of Charlemagne as being the holy rood of Saint Peter made from the wood of the true cross.

It was adorned with gems, the like of which the world has never seen before or since. The great diamond at the centre of the cross was said to be the same white stone that Caesar once gave to Cleopatra, Queen of Egypt, to seal their illicit union, and the four red rubies were taken from the iron crown of Alexander the Great. The Franks believed that the cross had magical powers. Charlemagne used it on feast days to heal his sick subjects. It was truly one of the wonders of the world.

My brother, I have travelled in many lands during my long life, and I have never found any other written record of the cross of Saint Peter. I had thought that perhaps it was lost when the pagans came into France four hundred years ago, but I do not now believe this to be true. There are men that I have spoken to in the city of Rouen who say that the monks of Marjean kept the cross of Charlemagne in a reliquary behind the high altar of the abbey church for generations, until an unsuccessful attempt was made to steal it and the cross was hidden.

The fate of the community at Marjean was no different than that of so many of the other monasteries of France. The great plague that many called the Black Death came there out of the east in the year of our Lord 1352, and there appear to have been no survivors. Marjean is indeed a desolate place, and I have taken no pleasure from my visits there. Some of the monastic library was preserved in a château nearby, but I found no record of the cross there or anywhere else. Only this. I passed through the town once more last year and found an old man living in the ruins of the monastery. He said that his father’s uncle was one of those monks killed by the great plague and that his father had told him when he was a child that the hiding place of the cross had been recorded in a book made by the monks. I asked the old man many questions about the book, and I formed the opinion that he was speaking of the holy Gospel of Saint Luke. I now feel sure that he was referring to the famous Marjean codex of which you will have doubtless heard yourself. But it too is missing, and I am no nearer to finding the cross of Saint Peter, if it does indeed still exist.

I am old in years, and I must turn away from the love of this world and make myself ready for the next. I leave to you this account, which is all that I know of Saint Peter’s cross.

May God be with you.

Andrew finished reading and handed the paper back to his daughter.

‘I remember when I first read that,’ he said. ‘In Rome before the war. I had gone there with Cade for a conference, but he wasn’t in the library when I found it. There was this little room at the back, and I don’t even know why I went in there. It was more like a cupboard, really. Shelves of old dusty religious commentaries and John’s letter neatly folded between the leaves of one of them. God knows how it got there. All I know is that it had been there for a long, long time. I remember it was early evening and I sat at a table in the summer twilight and made this copy, and then I showed it to Cade back at the hotel. I was excited. The city was ablaze with fires. Mussolini had just conquered Abyssinia, and I had found John of Rome. But Cade made me lose belief. The cross was an old wives’ tale, he said. An invention of jewel-crazy adventurers. It was a waste of time to even think of it.’

‘But he was lying. You knew that already, Dad. After all, it was you who told me that he was in Marjean at the end of the war. You thought he’d gone after the cross.’

‘I said it was possible.’

‘Well, it was more than possible. That was what he was doing. This diary proves it.’

‘I thought you said that it stopped in 1940.’

‘It does. But by then he’d visited Marjean twice and was planning a third visit. The war stopped him, but then the end of it gave him the opportunity to take what he wanted by force. That was when he stole the codex.’

‘Who from?’

‘From a Frenchman called Henri Rocard, who was the owner of the château at Marjean up until 1944, when he and his family were all murdered. Allegedly by the Germans.’

‘But you say it was Cade who did it?’

‘Yes, I’m sure of it. Him and that man Ritter. Look, go back to John of Rome’s letter. See near the end, where he talks about visiting Marjean? He says that some of the monastic library was preserved in a château nearby.’

‘But he also says that he found no record of the cross there or anywhere else,’ countered Blayne, reading from the letter.

‘Perhaps he didn’t look in the right places,’ said Sasha. ‘Cade realized early on that that was the most important sentence in the whole document. He says so in his diary. The year after you found the letter he went to Marjean and visited the château there. Henri Rocard was away from home, but Cade spoke to the wife. He describes her as proud and rude.’

‘Is that all?’ asked Blayne, laughing.

‘Pretty much. She didn’t invite him in. Said she knew nothing about the codex. Cade didn’t believe her, of course.’

‘So what did he do?’

‘He went to the records office in Rouen and settled down to do some research.’

‘On the Rocard family.’

‘Yes. And he got lucky. Not to begin with, but he was persistent.’

‘Always one of the professor’s qualities.’

‘He had no qualities. Look, let me tell you what’s in the diary, Dad,’ said Sasha impatiently. ‘There was no reference to the codex in the first place he looked. Land deeds and wills and the like from before John of Rome’s time right up until the Revolution. But then in 1793 there was something. Robespierre and the Jacobins were in power in Paris, and it was the time of the Terror, soon after the king was guillotined. Government agents sent out from Paris arrested a Georges Rocard as a counter-revolutionary, and a record was made of a search of his château at Marjean. Cade copied part of the record into his diary. It says that the government agents found no trace of the valuable document known as the Marjean codex.’

‘Just like John of Rome, when he searched for it four centuries earlier,’ said Blayne, sounding unimpressed.

‘But that’s not the point,’ said Sasha. ‘What’s important is that there were people at the end of the eighteenth century who believed that the codex was in the château at Marjean. There must have been some basis for that.’

‘Maybe,’ said her father, still unconvinced. ‘What happened to Georges Rocard?’

‘He didn’t escape, I’m afraid. Almost no one did. He was guillotined in Rouen a few weeks after his arrest. But his family got away to England, and Georges’s eldest son returned to Marjean and the château when the monarchy was restored in 1815. After the Battle of Waterloo.’

‘And this Henri Rocard was a descendant of his?’

‘Yes. Cade went back to the château, and this time Henri Rocard was there in person.’

‘Proud and rude like his wife?’

‘Worse, apparently. Rocard told Cade that he knew nothing about the codex, and when Cade persisted, Rocard and his old manservant set the dogs on him.’

‘Did they bite?’