По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

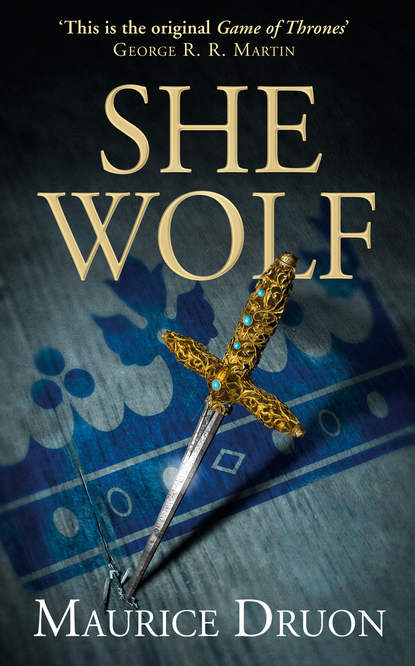

The She-Wolf

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘My lord,’ he said in a calm voice, ‘I feel sure that Seagrave is in no way to blame.’

‘He’s to blame for negligence and laziness; he’s to blame for allowing himself to be made a fool of; he’s to blame for not suspecting that a plot was being hatched under his nose; he’s to blame perhaps for his bad luck. And I never forgive bad luck. Though Seagrave is one of your protégés, Winchester, he shall be punished; and people will no longer be able to say that I’m unfair and that my favours are lavished only on your creatures. Seagrave will take Mortimer’s place in prison; and perhaps his successor will take care to keep a better watch. That, my son, is how you rule,’ the King added, coming to a halt in front of the heir to the throne.

The boy raised his eyes to him and immediately lowered them again.

Hugh the Younger, who knew how to turn Edward’s anger aside, threw back his head and, gazing up at the beams of the ceiling, said: ‘It’s the other criminal, dear Sire, who’s defying you most contemptuously. Bishop Orleton organized the whole thing himself and seems to fear you so little that he has not even taken the trouble to fly or go into hiding.’

Edward looked at Hugh the Younger with gratitude and admiration. How could one not be moved by that profile, by the fine attitudes he struck when speaking, by that high, well-modulated voice, and that way, at once so tender and respectful, of saying ‘dear Sire’, in the French manner, as sweet Gaveston, whom the barons and bishops had killed, used to do? But Edward had learned from experience, he knew how wicked men were and that you never won by coming to terms. He was determined never to be separated from Hugh, and all who opposed him would be pitilessly struck down, one after the other.

‘I announce to you, my lords, that Bishop Orleton will be brought before my Parliament to be tried and sentenced.’

Edward crossed his arms and looked round to see the effect of his words. The Archdeacon-Chancellor and the Bishop-Treasurer, though they were Orleton’s worst enemies, looked disapproving for they could not help standing by members of the cloth.

Henry Crouchback, who was by nature a wise and moderate man, could not help making an effort to bring the King back to the path of reason. He observed calmly that a bishop could be brought only before an ecclesiastical court consisting of his peers.

‘Everything has to have a beginning, Leicester. Conspiracy against Kings is not, so far as I know, taught by the Holy Gospels. Since Orleton has forgotten what should be rendered to Caesar, Caesar will remind him of it. Another favour I owe your family, Madame,’ the King went on, addressing Isabella, ‘since it was your brother Philippe V who, against my will, had Adam Orleton provided to the see of Hereford by his French Pope. Very well. He shall be the first prelate to be sentenced by the royal judiciary and his punishment shall be exemplary.’

‘Orleton was not originally hostile to you, Cousin,’ argued Crouchback, ‘nor would he have had any reason to become so if you had not opposed, or if your Council had not opposed, the Holy Father’s giving him the mitre. He is a man of great learning and strength of character. And you might even now perhaps, precisely because he is guilty, rally him to your support more easily by an act of clemency than by a trial at law which, among all your other difficulties, will draw upon you the anger of the clergy.’

‘Clemency, forbearance! Every time I’m scorned, provoked or betrayed, that’s all you have to say, Leicester. I was implored to spare the Baron of Wigmore, and how wrong I was to listen to that advice. You must admit that had I dealt with him as I did with your brother, the rebel would not be fleeing down the roads today.’

Crouchback shrugged his heavy shoulder and closed his eyes with an expression of weariness. How very irritating was Edward’s habit, which he considered royal, of calling the members of his family and his principal councillors by the names of their counties, addressing his cousin-german by shouting ‘Leicester’ instead of simply saying ‘my cousin’, as did everyone else including the Queen herself. And his bad taste in mentioning the execution of Thomas on every possible occasion, as if he gloried in it. Oh, what a strange man he was and what a bad king. To imagine you could behead your nearest relations and that no one resented it, to believe that mourning could be effaced by an embrace, to demand devotion from those you had wronged, and expect loyalty from everyone while you yourself were so cruelly inconstant.

‘No doubt you’re right, my lord,’ said Crouchback, ‘and since you’ve now reigned for sixteen years you must know the consequences of your actions. Hail your bishop before Parliament. I won’t stand in your way.’

And, muttering between his teeth so that no one should hear but the young Earl of Norfolk, he added: ‘My head may be set askew on my shoulders, but I’d rather keep it where it is.’

‘You must admit,’ Edward went on, his hand fluttering, ‘that it’s simply snapping his fingers at me to escape by piercing the walls of a tower I built myself especially so that no one should escape from it.’

‘Perhaps, Sire my Husband,’ the Queen said, ‘when it was building you were more preoccupied with the charms of the masons than with the solidity of the stonework.’

A sudden silence fell over the company. The insult was flagrant, and most unexpected. They all held their breath and stared, some with deference, some with hatred, at the rather fragile-looking woman who sat so upright and lonely in her chair, and held her own like this. Her lips drawn back a little and her mouth half-open, she was showing her fine little teeth; they were clenched, sharp, carnivorous. Isabella was clearly delighted with the blow she had dealt, whatever the consequences might be.

Hugh the Younger was blushing scarlet; Hugh the Elder made a pretence of not having heard.

Edward would certainly have his revenge. But what means would he adopt? The retort lagged. The Queen watched the drops of sweat pearling her husband’s brow. And nothing disgusts a woman more than the sweat of the man she has ceased to love.

‘Kent,’ cried the King, ‘I’ve made you Warden of the Cinque Ports and Governor of Dover. What are you doing here? Why aren’t you on the coast you’re supposed to be guarding and from which our felon must inevitably take ship?’

‘Sire my Brother,’ said the young Earl of Kent, somewhat taken aback, ‘it was you yourself who ordered me to accompany you on your journey …’

‘Well, now I’m giving you another. Go back to your county, have the towns and countryside searched for the fugitive, and see to it personally that every ship in port is visited.’

‘Send agents on board the ships and apprehend Mortimer, dead or alive, if he embarks,’ said Hugh the Younger.

‘Sound advice, Gloucester,’ Edward approved. ‘As for you, Stapledon …’

The Bishop of Exeter stopped gnawing at his thumbnail and murmured: ‘My lord …’

‘You will make haste to London and go immediately to the Tower on the pretext of checking the Treasure, which is in your charge. Then, furnished with an order under my seal, you will take command of the Tower and supervise it till a new constable is appointed. Baldock will make out the commissions at once, so that you will have the necessary powers.’

Henry Crouchback, his eyes turned towards the window and his ear propped on his shoulder, seemed to be dreaming. He was calculating that six days had elapsed since Mortimer’s escape,

that it would take at least eight days more before these orders could be executed, and that unless he was a fool, which Mortimer most certainly was not, he must already have left the kingdom. He congratulated himself on having joined with the greater part of the bishops and lords who, after Boroughbridge, had succeeded in obtaining a reprieve for the Baron of Wigmore. For now that Mortimer had escaped, the opposition to the Despensers might well find the leader it had lacked since the death of Thomas of Lancaster, and a stronger, cleverer, and more effective leader than Thomas had been.

The King’s back bent sinuously; Edward pirouetted on his heels and came face to face with his wife.

‘What’s more, Madame, I hold you entirely responsible. And, in the first place, let go that hand you’ve been holding ever since I came into the room. Let go Lady Jeanne’s hand!’ cried Edward, stamping his foot. ‘It’s going surety for a traitor to keep his wife so ostentatiously at your side. The people who helped Mortimer to escape well knew they had the Queen’s support. Besides, you can’t escape without money. Treason has to be paid for. Walls aren’t pierced without gold. But the conduit’s evident: the Queen to her lady-in-waiting, the lady-in-waiting to the bishop, the bishop to the rebel. I shall have to look more closely into your privy purse.’

‘Sire my Husband, I think my privy purse is already sufficiently controlled,’ said Isabella, indicating Lady Despenser.

Hugh the Younger seemed suddenly to have lost interest in the discussion. The King’s anger was turning at last, as indeed it usually did, against the Queen. Edward had found an object for his vengeance, and Hugh felt all the more triumphant. He picked up a book that was lying near by and which Lady Mortimer had been reading to the Queen before the Count de Bouville had come in. It was a collection of the lays of Marie of France; the silk marker signalled this passage:

En Lorraine ni en Bourgogne,

Ni en Anjou ni en Gascogne,

En ce temps ne pouvait trouver

Si bon ni si grand chevalier.

Sous ciel n’était dame ou pucelle,

Qui tant fût noble et tant fût belle

Qui n’en voulût amour avoir …

‘France, it’s always France. She never reads anything that doesn’t relate to that country,’ Hugh thought. ‘And who’s the knight they’re dreaming of in their thoughts? Mortimer, no doubt …’

‘My lord, I do not superintend the charities,’ said Alienor Despenser.

The favourite looked up and smiled. He would congratulate his wife on that remark.

‘I foresee I shall have to give up my charities too,’ said Isabella. ‘I shall soon have no queenly prerogative left, not even that of charity.’

‘And also, Madame, for the love you bear me, of which everyone is aware,’ Edward went on, ‘you must part with Lady Mortimer, for not a soul in the kingdom will understand her being near you now.’

And now the Queen turned pale and sank back a little in her chair. Lady Jeanne’s long pale hands were trembling.

‘A wife, Edward, cannot be held responsible for all her husband’s actions. I am an example of it myself. You must believe that Lady Mortimer has as little to do with her husband’s errors as I have with your sins, supposing you commit any.’

But this time the attack was unsuccessful.

‘Lady Jeanne will leave for Wigmore Castle, which from now on will be under the supervision of my brother of Kent, and will remain there until I have decided what to do with the property of a man whose name will never again be mentioned in my presence except to sentence him to death. I believe, Lady Jeanne, that you would prefer to go to your house of your own free will rather than be taken there by force.’

‘I see,’ said Isabella, ‘that you wish me to be left utterly alone.’

‘What do you mean by alone, Madame?’ cried Hugh the Younger in his fine, well-modulated voice. ‘Are we not all your loyal friends, being the King’s? And is not Madame Alienor, my devoted wife, a faithful companion to you? That’s a pretty book you have there,’ he added, pointing to the volume, ‘and beautifully illuminated; would you be kind enough to lend it to me?’