По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

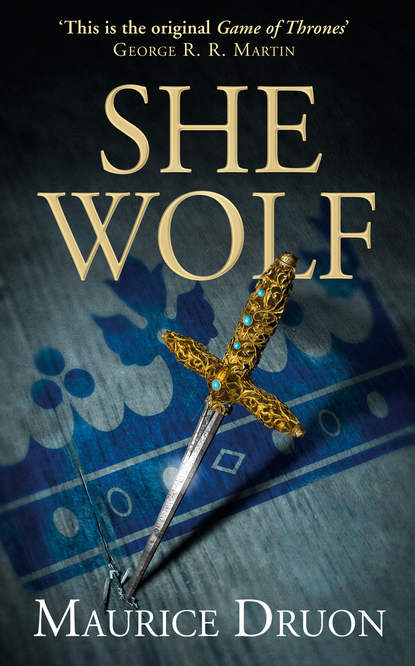

The She-Wolf

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Alspaye?’ Mortimer whispered.

‘He’ll go with us,’ the barber replied, attending to the other side of Mortimer’s face.

‘The Bishop?’ the prisoner asked again.

‘He’ll be waiting for you outside, after dark,’ said the barber, who began at once to talk again at the top of his voice of the heat, the parade that was to take place that morning, and the games that would fill the afternoon.

The shaving done, Roger Mortimer rinsed his face and dried it with a towel. He did not even feel its rough contact.

When barber Ogle had gone with the turnkey, the prisoner put both hands to his chest and took a deep breath. With difficulty, he prevented himself shouting aloud: ‘Be ready tonight!’ The words were ringing through his head. Could it really be true that it was for tonight, at last?

He went to the pallet bed on which his companion in prison was sleeping.

‘Uncle,’ he said, ‘it’s tonight.’

The old Lord of Chirk turned over with a groan, looked at his nephew with his pale eyes that shone with a green glow in the shadowy dungeon and replied wearily: ‘No one ever escapes from the Tower of London, my boy, no one. Neither tonight, nor ever.’

Young Mortimer showed his irritation. Why should a man who, at worst, had so comparatively little of life to lose, be so obstinately discouraging and refuse to take any risks whatever? He did not reply so as not to lose his temper. Though they spoke French together, as did the Court and the nobility of Norman origin, while servants, soldiers and the common people spoke English, they were still afraid of being overheard.

He went back to the narrow window and looked out at the parade, which he could see only from ground-level, with the happy feeling that he was perhaps watching it for the last time.

The soldiers’ leggings passed to and fro at eye-level; their thick leather boots stamped the paving. Roger Mortimer could not but admire the precision of the archers’ drill, those wonderful English archers who were the best in Europe and could shoot as many as twelve arrows a minute.

In the centre of the Green, Alspaye, the Lieutenant, standing rigid as a post, was shouting orders at the top of his voice. He then reported the guard to the Constable. At first sight, it was difficult to understand why this tall, pink and white young man, who was so attentive to his duty and so clearly concerned to do the right thing, should have agreed to betray his charge. There could be no doubt that he had been persuaded to it for other reasons than mere money. Gerard de Alspaye, the Lieutenant of the Tower of London, wished, as did many officers, sheriffs, bishops and lords, to see England freed from the bad ministers surrounding the King; in his youthful way he was dreaming of a great career; and, what was more, he loathed and despised his immediate superior, the Constable, Seagrave.

The Constable, a one-eyed, flabby-cheeked and incompetent drunkard, owed his high position in fact to the protection of those bad ministers. Overtly indulging in the very practices King Edward displayed before his Court, the Constable was inclined to use the garrison of the Tower as a harem. He liked tall, fair young men; and Lieutenant Alspaye’s life had become a hell, for he was religious and had no vicious tendencies. Alspaye had indeed repelled the Constable’s advances and, as a result, had become the object of his relentless persecution. From sheer vengeance Seagrave seized every opportunity to plague and vex him. Slothful though he was, this one-eyed man found the leisure to be cruel. And now, as he inspected the men, he mocked and insulted his second-in-command over the merest trifles: a fault in the men’s dressing, a spot of rust on the blade of a dagger, a minute tear in the leather of a quiver. His single eye searched only for faults.

Though it was a Feast Day, on which punishments were generally remitted, the Constable, faulting their equipment, ordered three soldiers to be whipped on the spot. They happened to be three of the best archers. A sergeant was sent to fetch the rods. The men who were to be punished had to take their breeches down in front of the ranks of their comrades. The Constable seemed much amused at the sight.

‘If the guard’s no better turned out next time, Alspaye, it’ll be you,’ he said.

Then the whole garrison, with the exception of the sentries on the gates and ramparts, gathered in the Chapel to hear Mass and sing canticles.

Listening at his window, the prisoner could hear their rough, untuneful voices. ‘Be ready tonight, my lord …’ The ex-Lieutenant of the King in Ireland could think of nothing except that he might perhaps be free this very night. But there was a whole day in which to wait, hope, and indeed fear: fear that Ogle would make some silly mistake in executing the agreed plan, fear that Alspaye would succumb to a sense of duty at the last moment. There was a whole day in which to dwell on all the obstacles, all the hazards that might prejudice his escape.

‘It’s better not even to think of it,’ he thought, ‘and take it for granted that all will go well. It’s always something you’ve never even considered that goes wrong. Nevertheless, it’s also the stronger will that triumphs.’ And yet his mind, inevitably, returned again and again to the same anxieties. ‘In any event, there’ll still be the sentries on the walls …’

He jumped quickly back from the window. The raven had approached stealthily along the wall, and this time it was a near thing that it did not get the prisoner’s eye.

‘Oh, Edward, Edward, that’s going too far,’ Mortimer said between clenched teeth. ‘If ever I’m going to succeed in strangling you, it must be today.’

The garrison was coming out of the Chapel and going into the refectory for the traditional feast.

The turnkey reappeared at the dungeon door, accompanied by a warder with the prisoners’ food. For once, the bean soup was accompanied by a slice of mutton.

‘Try to stand up, Uncle,’ Mortimer said.

‘They even deprive us of Mass, as if we were excommunicated,’ said the old Lord.

He insisted on eating on his pallet, and indeed scarcely touched his portion.

‘Have my share, you need it more than I,’ he said to his nephew.

The turnkey had gone. The prisoners would not be visited again till evening.

‘Have you really made up your mind not to go with me, Uncle?’ Mortimer asked.

‘Go with you where, my boy? No one ever escapes from the Tower. It has never been done. Nor does one rebel against one’s king. Edward’s not the best sovereign England’s had, indeed he’s not, and those two Despensers deserve to be here instead of us. But you don’t choose your king, you serve him. I should never have listened to you and Thomas of Lancaster, when you took up arms. Thomas has been beheaded, and look where we are.’

It was the hour at which his uncle, having swallowed a few mouthfuls of food, would sometimes talk in a monotonous, whining voice, recapitulating over and over again the same complaints his nephew had heard for the last eighteen months. At sixty-seven, the elder Mortimer was no longer recognizable as the handsome man and great lord he had been, famous for the fabulous tournament he had given at his castle of Kenilworth, which had been the talk of three generations. The nephew did his best to rekindle a few embers in the old man’s exhausted heart. He could see his white locks hanging lank in the shadows.

‘In any case my legs would fail me,’ the old man added.

‘Why not get out of bed and try them out a little? In any case, I’ll carry you. I’ve told you so.’

‘Oh, yes, I know! You’ll carry me over the walls and into the water though I can’t swim. You’ll carry my head to the block, that’s what you’ll do, and yours too. God may well be working for our deliverance, and you’ll spoil it all by this stubborn folly of yours. It’s always the same; there’s rebellion in the Mortimer blood. Remember the first Roger, the son of the bishop and the daughter of King Herfast of Denmark. He defeated the whole army of the King of France under the walls of his castle of Mortemer-en-Bray.

And yet he so greatly offended the Conqueror, our kinsman, that all his lands and possessions were taken from him.’

The younger Roger sat on a stool, crossed his arms, closed his eyes, and leaned backwards a little to support his shoulders against the wall. Every day he had to listen to an account of their ancestors, hear for the hundredth time how Ralph the Bearded, son of the first Roger, had landed in England in the train of Duke William, how he had received Wigmore in fief, and why the Mortimers had been powerful in four counties ever since.

In the refectory the soldiers had finished eating and were bawling drinking songs.

‘Please, Uncle,’ Mortimer said, ‘do leave our ancestors alone for a while. I’m in no such hurry to go to join them as you are. I know we’re descended from royal blood. But royal blood is of small account in prison. Will Herfast’s sword set us free? Where are our lands, and are we paid our revenues in this dungeon? And when you’ve repeated once again the names of all our female ancestors – Hadewige, Mélisinde, Mathilde the Mean, Walcheline de Ferrers, Gladousa de Braouse – am I to dream of no women but them till I draw my last breath?’

For a moment the old man was nonplussed and stared absent-mindedly at his swollen hands and their long, broken nails, then he said: ‘Everyone fills his prison life as best he can, old men with the lost past, young men with tomorrows they’ll never see. You believe the whole of England loves you and is working on your behalf, that Bishop Orleton is your faithful friend, that the Queen herself is doing her best to save you, and that in a few hours you’ll be setting out for France, Aquitaine, Provence or somewhere of the sort. And that the bells will ring out in welcome all along your road. But, you’ll see, no one will come tonight.’

With a weary gesture, he passed his hands across his eyes, then turned his face to the wall.

Young Mortimer went back to the window, put a hand out through the bars and let it lie as if dead in the dust.

‘Uncle will now doze till evening,’ he thought. ‘He’ll make up his mind to come at the last moment. But he won’t make it any easier; indeed, it may well fail because of him. Ah, there’s Edward!’

The raven stopped a little way from the motionless hand and wiped its big black beak against its foot.

‘If I strangle it, I shall succeed in escaping. If I miss it, I shall fail.’

It was no longer a game, but a wager with destiny. The prisoner needed to invent omens to pass the time of waiting and quiet his anxiety. He watched the raven with the eye of a hunter. But as if it realized the danger, the raven moved away.

The soldiers were coming out of the refectory, their faces all lit up. They dispersed over the courtyard in little groups for the games, races and wrestling that were a tradition of the Feast. For two hours, naked to the waist, they sweated under the sun, competing in throwing each other or in their skill in casting maces at a wooden picket.

Then he heard the Constable cry: ‘The King’s prize! Who wants to win a shilling?’

Then, as it drew towards evening, the soldiers went to wash in the cisterns and, noisier than in the morning, talking of their exploits or their defeats, they went back to the refectory to eat and drink once more. Anyone who was not drunk on the night of St Peter ad Vincula earned the contempt of his comrades. The prisoner could hear them getting down to the wine. Dusk fell over the courtyard, the blue dusk of a summer’s evening, and the stench of mud from the river-bank became perceptible once again.

Suddenly a long, fierce, hoarse croaking, the sort of animal cry that makes men uneasy, rent the air from beyond the window.

‘What’s that?’ the old Lord of Chirk asked from the far end of the dungeon.