По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

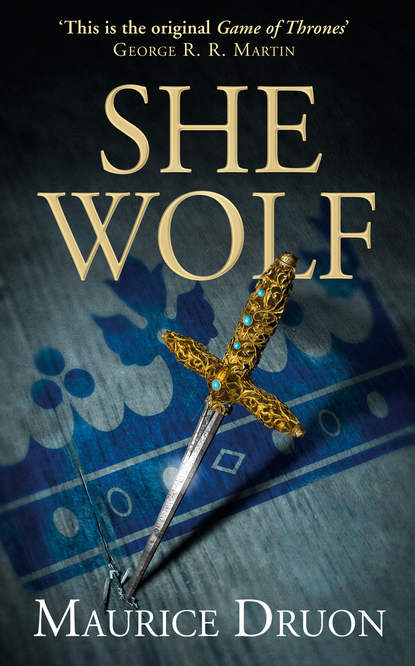

The She-Wolf

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Madame,’ replied Lady Jeanne, ‘you do more to sustain my courage than I do to maintain yours. And you’ve taken a great risk in keeping me with you when my husband is in prison.’

They all three went on talking in low voices, for the whisper and the aside had become necessary habits in that Court where you were never alone and the Queen lived amid enmity.

In a corner of the room three maidservants were embroidering a counterpane for Lady Alienor Despenser, the favourite’s wife, who was playing chess by an open window with the heir-apparent. A little farther off, the Queen’s second son, who had had his seventh birthday three weeks earlier, was making a bow from hazel switch; while the two little girls, Jane and Alienor, respectively five and two, were sitting on the floor, playing with rag dolls.

Even as she moved the pieces over the ivory chess-board, Lady Despenser never for a moment stopped watching the Queen and trying to hear what she was saying. Her forehead was smooth but curiously narrow, her eyes were bright but too close together, her mouth was sarcastic; without being altogether hideous, there was nevertheless apparent that quality of ugliness which is imprinted by a wicked nature. A descendant of the Clare family, she had had a strange career, for she had been sister-in-law to the King’s previous lover, Piers Gaveston, whom the barons under Thomas of Lancaster had executed eleven years before, and she was now the wife of the King’s current lover. She derived a morbid pleasure from assisting male amours, partly to satisfy her love of money and partly to gratify her lust of power. But she was a fool. She was prepared to lose her game of chess for the mere pleasure of saying provocatively: ‘Check to the Queen! Check to the Queen!’

Edward, the heir-apparent, was a boy of eleven; he had a rather long, thin face, and was by nature reserved rather than timid, though he nearly always kept his eyes on the ground; at the moment he was taking advantage of his opponent’s mistake to do his best to win.

The August breeze was blowing gusts of warm dust through the narrow, arched window; but, when the sun sank, it would turn cool and damp again within the thick, dark walls of ancient Kirkham Priory.

There was a sound of many voices from the Chapter House where the King was holding his itinerant Council.

‘Madame,’ said the Count de Bouville, ‘I would willingly dedicate all the remainder of my days to your service, could they be useful to you. It would be a pleasure to me, I assure you. What is there for me to do here below, since I am a widower and my sons are out in the world, except to use the last of my strength to serve the descendants of the King who was my benefactor? And it is with you, Madame, that I feel myself nearest to him. You have all his strength of character, the way of talking he had, when he felt so disposed, and all his beauty which was so impervious to time. When he died, at the age of forty-six, he looked barely more than thirty. It will be the same with you. No one would ever guess you have had four children.’

The Queen’s face brightened into a smile. Surrounded, as she was, by so much hatred, she was grateful to be offered this devotion; and, her feelings as a woman continually humiliated, it was sweet to hear her beauty praised, even if the compliment was from a fat old man with white hair and spaniel’s eyes.

‘I am already thirty-one,’ she said, ‘of which fifteen years have been spent as you see. It may not mark my face; but my spirit bears the wrinkles. Indeed, Bouville, I would willingly keep you with me, were it possible.’

‘Alas, Madame, I foresee the end of my mission, and it has not had much success. King Edward has already twice indicated his surprise, since he has already delivered the Lombard up to the High Court of the King of France, that I should still be here.’

For the official pretext for Bouville’s embassy was a demand for the extradition of a certain Thomas Henry, a member of the important Scali company of Florence; the banker had leased certain lands from the Crown of France, had pocketed the considerable revenues, failed to pay what he owed to the French Treasury, and had ultimately taken refuge in England. The affair was serious enough, of course, but it could easily have been dealt with by letter, or by sending a magistrate, and most certainly had not required the presence of an ex-Great Chamberlain, who sat in the Privy Council. In fact, Bouville had been charged with another and more difficult diplomatic negotiation.

Monseigneur Charles of Valois, the uncle both of the King of France and Queen Isabella, had taken it into his head the previous year to marry off his fifth daughter, Marie, to Prince Edward, the heir-apparent to the throne of England. Monseigneur of Valois – who was unaware of it in Europe? – had seven daughters whose marriages had been a continual source of anxiety to this turbulent, ambitious and prodigal prince, who inevitably used his children for the promotion of his vast intrigues. The seven daughters were by three different marriages for Monseigneur Charles, during the course of his restless life, had suffered the misfortune of twice becoming a widower.

You needed a clear mind not to lose your way amid this complicated family tree, to know, for instance, when Madame Jeanne of Valois was mentioned, whether the Countess of Hainaut was meant or the Countess of Beaumont, the wife of Robert of Artois. Just to help matters, the two girls had the same name. As for Catherine, heiress to the phantom throne of Constantinople, who was by the second marriage, she had wedded in the person of Philip of Tarantum, Prince of Achaia, an elder brother of her father’s first wife. It was, indeed, something of a puzzle!

And now Monseigneur Charles was proposing that the elder daughter of his third marriage should wed his great-nephew of England.

At the beginning of the year, Monseigneur of Valois had sent a mission consisting of Count Henry de Sully, Raoul Sevain de Jouy and Robert Bertrand, known as the ‘Knight of the Green Lion’. To curry favour with Edward II, these ambassadors had accompanied him on an expedition against the Scots; but, at the Battle of Blackmore, the English had fled and allowed the French ambassadors to fall into the hands of the enemy. Their freedom had had to be negotiated and their ransoms paid. When, at last after a number of unpleasant adventures, they had been released, Edward had replied, evasively and dilatorily, that his son’s marriage could not be decided on so quickly, that the matter was of such great importance that he could make no contract without the advice of his Parliament, and that Parliament would be summoned to discuss the matter in June. He wished to link this affair with the homage he was due to pay the King of France for the Duchy of Aquitaine. And then, when Parliament had at last been convoked, the question had not even been discussed.

In his impatience, Monseigneur of Valois had taken the first opportunity of sending over the Count de Bouville, whose devotion to the Capet family was undoubted and who, though lacking in genius, had considerable experience of similar missions. In the past, Bouville had negotiated in Naples, on the instructions of Valois himself, the second marriage of Louis X with Clémence of Hungary; he had been Curator of the Queen’s stomach after the Hutin’s death, but that was not a period he cared to recall. He had also carried out a number of negotiations in Avignon with the Holy See; and in matters concerning family relationships his memory was faultless, he knew all the infinitely complex inter-weavings that formed the web of the royal houses’ alliances. Honest Bouville was much vexed at having to go back this time with empty hands.

‘Monseigneur of Valois will be very angry indeed,’ he said, ‘since he has already asked the Holy Father for a licence for this marriage.’

‘I’ve done all I can, Bouville,’ the Queen said, ‘and you can judge from that what weight I carry here. But I do not regret it as much as you do; I do not want another princess of my family to suffer what I have suffered here.’

‘Madame,’ Bouville replied, lowering his voice still further, ‘do you doubt your son? He seems to take after you rather than after his father, thank God. I remember you at his age, in the garden of the Palace of the Cité, or at Fontainebleau …’

He was interrupted. The door opened to give entrance to the King of England. He hurried in; his head was thrown back and he was stroking his blond beard with a nervous gesture which, in him, was a sign of irritation. He was followed by his usual councillors, the two Despensers, father and son, Chancellor Baldock, the Earl of Arundel and the Bishop of Exeter. The King’s two half-brothers, the Earls of Kent and Norfolk, who had French blood since their mother was the sister of Philip the Fair, formed part of his entourage, but rather against their will so it seemed; and this was also true of Henry of Leicester. The last was a square-looking man, with bright, rather protruding eyes, who was nicknamed Crouchback owing to a malformation of the neck and shoulders which compelled him to hold his neck completely askew, and gave the armourers who had to forge his cuirasses a good deal of difficulty. A number of ecclesiastics and local dignitaries also pressed into the doorway.

‘Have you heard the news, Madame?’ cried King Edward, addressing the Queen. ‘It will doubtless please you. Your Mortimer has escaped from the Tower.’

Lady Despenser, at the chess-board, gave a start and uttered an exclamation of indignation as if the Baron of Wigmore’s escape were a personal insult.

Queen Isabella gave no sign, either by altering her attitude or expression; only her eyelids blinked a little more rapidly over her beautiful blue eyes, and her hand, beneath the folds of her dress, furtively sought that of Lady Jeanne Mortimer, as if encouraging her to be strong and calm. Fat Bouville had got to his feet and moved a little apart, feeling himself unwanted in this matter which purely concerned the English Crown.

‘He is not my Mortimer, Sire,’ replied the Queen. ‘Lord Mortimer is your subject, I should have thought, rather than mine; and I am not accountable for the actions of your barons. You kept him in prison; he has escaped; it’s the common form.’

‘And that shows you approve him! Don’t restrain your joy, Madame. In the days when Mortimer deigned to appear at my Court, you had no eyes except for him; you were continually extolling his merits, and you have always put down the crimes he has committed against me to his greatness of soul.’

‘But was it not you, yourself, Sire my Husband, who taught me to love him at the time he was conquering, on your behalf and at the peril of his life, the Kingdom of Ireland, which indeed you had great difficulty in holding without him? Was that a crime?’

Put out of countenance by this attack, Edward looked spitefully at his wife and found some difficulty in replying.

‘Well, your friend’s on the run now, running hard towards your country no doubt!’

As he talked, the King was walking up and down the room, working off his useless agitation. The jewels hanging from his clothes quivered at every step he took. The rest of the company followed him with their eyes, turning their heads from side to side, as if they were watching a game of tennis. There was no doubt that King Edward was a fine-looking man, muscular, lithe and alert. He kept himself fit with games and exercises and had so far resisted any tendency to stoutness though his fortieth birthday was close at hand; he had an athlete’s constitution. But if you looked closer, you were struck by the fact that his forehead was utterly unlined, as if the anxieties of power had failed to mark him, by the pouches beginning to form beneath his eyes, by the uncertain line of the curve of the nostril, and by the long chin beneath the thin, curled beard. It was not an energetic or authoritative chin, nor even a really sensual one, but merely too big and too elongated a chin. There was twenty times more determination in the Queen’s little chin than there was in this ovoid jaw whose weakness the silky beard could not conceal. And the hand he passed from time to time across his face was flaccid; it fluttered aimlessly and then tugged at a pearl sewn to the embroidery of his tunic. His voice, which he hoped and believed was imperious, merely suggested lack of control. His back, which was wide enough, curved unpleasantly from the neck to the waist, as if the spine lacked substance. Edward had never forgiven his wife for having one day advised him to avoid showing his back if he wished to gain the respect of his barons. His knee was shapely and his leg well-turned; indeed, these were the best points of this man who was so little suited to his responsibilities, and to whom a crown had fallen by some curious inadvertence on the part of Fate.

‘Haven’t I enough worries and difficulties already?’ he went on. ‘The Scots are always threatening and invading my frontiers and, when I give battle, my armies run away. And how can I defeat them when my bishops treat with them without my permission, when there are so many traitors among my vassals, and when my barons of the Marches raise troops against me on the principle that they hold their lands by their swords, when some twenty-five years ago – have they forgotten? – it was determined and ordered otherwise by King Edward, my father. But they learned at Shrewsbury and Boroughbridge what it costs to rebel against me, didn’t they, Leicester?’

Henry of Leicester shook his great, crippled head; it was hardly a courteous way of reminding him of the death of his brother, Thomas of Lancaster, who had been beheaded sixteen months before, when twenty great lords had been hanged and as many more imprisoned.

‘Indeed, Sire my Husband, we have all noticed that the only battles you can win are against your own barons,’ Isabella said.

Once again Edward looked at her with hatred in his eyes. ‘What courage,’ Bouville thought, ‘what courage this noble Queen has!’

‘Nor is it altogether fair,’ she went on, ‘to say that they rebelled against you because they hold their rights by their swords. Was it not rather over the rights of the county of Gloucester which you wanted to give to Sir Hugh?’

The two Despensers drew closer together as if to make common front. Lady Despenser, the younger, sat up stiffly at the chess-board. She was the daughter of the late Earl of Gloucester. Edward II stamped his foot on the flagstones. Really, the Queen was impossible. She never opened her mouth except to tease him with his errors and mistakes of government.

‘I give the great fiefs to whom I will, Madame. I give them to those who love me and serve me,’ Edward cried, putting his hand on the younger Hugh’s shoulder. ‘On whom else can I rely? Where are my allies? What help, Madame, does your brother of France, who should behave to me as if he were mine, since after all it was in that hope I was persuaded to take you for wife, bring me? He demands that I go and pay him homage for Aquitaine, and that is all the help I get from him. And where does he send me his summons, to Guyenne? Not at all. He has it brought to me here in my Kingdom, as if he were contemptuous of feudal custom, or wished to offend me. One might almost think he believed himself also suzerain of England. Besides, I have paid this homage, indeed I have paid it too often, once to your father, when I was nearly burnt alive in the fire at Maubuisson, and then again to your brother Philippe, three years ago, when I went to Amiens. Considering the frequency with which the kings of your family die, Madame, I shall soon have to go to live on the Continent.’

The lords, bishops, and Yorkshire notables, who were standing at the back of the room, looked at each other, by no means afraid, but shocked rather at this impotent anger which strayed so far from its object, and revealed to them not only the difficulties of the kingdom, but also the character of the King. Was this the sovereign who asked them for subsidies for his Treasury, to whom they owed obedience in everything, and for whom they were to risk their lives when he summoned them to take part in his wars? Lord Mortimer must have had good reasons for rebellion.

Even the intimate councillors seemed ill at ease, though they well knew the King’s habit of recapitulating, even in his correspondence, all the troubles of his reign whenever a new difficulty arose.

Chancellor Baldock was mechanically rubbing his Adam’s apple above his archidiaconal robe. The Bishop of Exeter, the Lord Treasurer, was nervously biting his thumbnail and watching his neighbours out of the corner of his eye. Only Hugh Despenser the Younger, too curled, scented and overdressed for a man of thirty-three, showed satisfaction. The King’s hand resting on his shoulder made it clear to everyone how important and powerful he was.

He had a short, snub nose and a well-shaped mouth and was now raising and lowering his chin like a horse pawing the ground, as he approved every word Edward said with a little throaty murmur. His expression seemed to imply: ‘This time things have really gone too far; we shall have to take stern measures!’ He was thin, tall, rather narrow-chested and had a bad, spotty skin.

‘Messire de Bouville,’ King Edward said suddenly, turning to the ambassador, ‘you will reply to Monseigneur of Valois that the marriage he proposes, and of which we appreciate the honour, will most certainly not take place. We have other views for our eldest son. And we shall thus put a term to the deplorable custom by which the Kings of England take their wives from France, without ever deriving any benefit from it.’

Fat Bouville paled at the affront and bowed. He looked sadly at the Queen and went out.

The first and most unexpected consequence of Roger Mortimer’s escape was that the King of England was breaking his traditional alliance. By this outburst he had wanted to wound his wife; but he had also succeeded in wounding his half-brothers of Norfolk and Kent, whose mother was French. The two young men turned to their cousin Crouchback, who shrugged his heavy shoulder in resigned indifference. Without reflection, the King had casually alienated for ever the powerful Count of Valois who, as everyone knew, governed France in the name of his nephew Charles the Fair. Caprices such as this have sometimes lost kings both their thrones and their lives.

Young Prince Edward, still motionless by the window, was silently watching his mother and judging his father. After all, it was his marriage that was being discussed and he was allowed to have no say in it. But if he had been asked to choose between his English and French blood, he would have shown a preference for the latter.

The three younger children had stopped playing: the Queen signed to the maidservants to take them away.

And then, with the greatest calm, looking the King straight in the eye, she said: ‘When a husband hates his wife it is natural he should hold her responsible for everything.’

Edward was not the man to make a direct answer to that.

‘My whole Tower guard dead-drunk,’ he cried, ‘the Lieutenant in flight with that felon, and my Constable sick to death with the drug they gave him. Unless the traitor’s malingering to avoid the punishment he deserves. It was up to him to see my prisoner did not escape. Do you hear, Winchester?’

Hugh Despenser the Elder, who had been responsible for the appointment of Constable Seagrave, bowed to the storm. He was thin and narrow-shouldered, with a stoop that was in part natural and in part acquired during a long career as a courtier. His enemies had nicknamed him ‘the weasel’. Cupidity, envy, meanness, self-seeking, deceit, and all the gratifications these vices can procure for their possessor were manifest in the lines of his face and beneath his red eyelids. And yet he was not lacking in courage; but he had human feelings only for his son and a few rare friends, of which Seagrave indeed was one. You could better understand the son’s character when you had observed the father for a moment.