По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

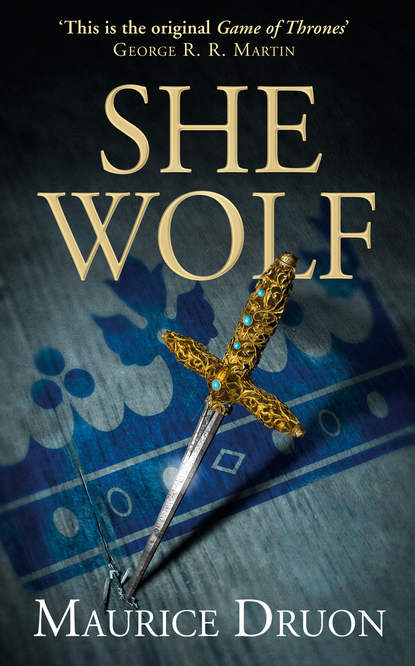

The She-Wolf

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Tolomei listened and watched his two visitors. They both seemed to him very young. How old was Robert of Artois? Thirty-five, thirty-six? And the Englishman seemed much the same age. Everyone under sixty seemed to him astonishingly young. How much they still had to do, how many emotions still to suffer, battles to fight and ambitions to realize. How many mornings they would see that he would never know. How often these two men would awaken and breathe the air of a new day, when he himself was under the ground.

And what kind of man was Lord Mortimer? The clear-cut face, the thick eyebrows, the straight line of the eyelids across the flint-coloured eyes, the sombre clothes, the way he crossed his arms, the silent, haughty assurance of a man who had sat on the pinnacle of power and intended to preserve all his dignity in exile, even the automatic gesture with which Mortimer ran his finger across the short white scar on his lip, all pleased the old Sienese. And Tolomei felt he would like this lord to recover his happiness. For some time past, Tolomei had acquired almost a taste for thinking of others.

‘Are the regulations concerning the export of currency to be promulgated in the near future, Monseigneur?’ he asked.

Robert of Artois hesitated before replying.

‘Oh, of course, I don’t suppose you’ve been told yet …’ Tolomei added.

‘Of course, naturally I’ve been told. You very well know that nothing is done without my advice being asked by the King, and by Monseigneur of Valois above all. The order will be sealed in two days’ time. No one will be permitted to export gold or silver currency stamped with the die of France from the kingdom. Only pilgrims will be allowed to provide themselves with a few small coins.’

The banker pretended to attach no greater importance to this piece of news than he had to the price of candles or the adulteration of jam. But he was already thinking: ‘That means foreign currency will alone be permitted to be taken out of the kingdom; as a result, it will increase in value … What a help these blabbers are to us in our profession. How the boasters give us for so little the information they could sell so dear.’

‘So, my lord,’ he went on, turning to Mortimer, ‘you intend to establish yourself in France? What can I provide?’

It was Robert who replied.

‘What a great Lord needs to maintain his rank. You’re accustomed enough to that, Tolomei.’

The banker rang a handbell. He told the servant to bring his great book, and added: ‘If Messer Boccaccio has not left, ask him to wait till I’m free.’

The book was brought, a thick volume covered in black leather, smooth from much handling, and its vellum leaves held together by adjustable fastenings so that more leaves could be added as desired. This device enabled Messer Tolomei to keep the accounts of his important clients in alphabetical order and not to have to search for scattered pages. The banker placed the volume on his knees, and opened it with some ceremony.

‘You’ll find yourself in good company, my lord,’ he said. ‘Look, honour where honour is due, my book begins with the Count of Artois. You’ve a great many pages, Monseigneur,’ he added with a little laugh, looking at Robert. ‘Here’s the Count de Bouville for his missions to the Pope and to Naples. And here’s Madame the Queen Clémence …’

The banker inclined his head in deference.

‘Oh, she gave us a lot of anxiety after the death of Louis X: it was as if mourning put her in a frenzy of spending. The Holy Father himself exhorted her to moderation in a special letter, and she had to pawn her jewels with me to pay off her debts. Now she’s living in the Palace of the Templars which she exchanged against the Castle of Vincennes; she gets her dowry and seems to have found peace.’

He went on turning over the pages which rustled under his hand.

‘And now I’m boasting,’ he thought. ‘But one must do something to emphasize the importance of the services one renders, and to show that one’s not dazzled by a new borrower.’

He had a clever way of letting them see the names while concealing the figures with his arm. He was only being half-indiscreet. And, after all, he had to admit that his whole life was contained in this book, and that he enjoyed every opportunity of looking through it. Each name, each figure evoked so many memories, so many intrigues, so many secrets of which he had been the recipient, and so many entreaties by which he had been able to measure his power. Each figure commemorated a visit, a letter, a clever deal, a feeling of sympathy or one of harshness towards a negligent debtor. It was nearly fifty years since Spinello Tolomei, on his arrival from Siena, had begun by doing the rounds of the fairs of Champagne, and then come to live here, in the Rue des Lombards, to keep a bank.

Another page, and another, which caught in his broken nails. A black line was drawn through a name.

‘Here’s Messer Dante Alighieri, the poet, but only for a small sum, when he came to Paris to visit Queen Clémence after she had become a widow. He was a great friend of hers, as he had been of King Charles of Hungary, Madame Clémence’s father. I remember him sitting in your chair, my lord. A man without a spark of kindness. He was the son of a money-changer; and he talked to me for a whole hour with great contempt of the financier’s trade. But he could afford to be ill-natured and go off and get drunk with women in houses of ill-fame, while talking of his pure love for the Lady Beatrice. He made our language sing as no one before him has ever done. And how he described the Inferno, my lord! You have not read it? Oh, you must have it translated. One trembles to think that it may perhaps be like that. Do you know that in Ravenna, where Messer Dante spent his last years, the people used to scatter from his path in fear because they thought he really had gone down into Hell? And, even now, many people refuse to believe that he died two years ago, for they say he was a magician and could not die. He certainly didn’t like banking, nor indeed Monseigneur of Valois who exiled him from Florence.’

The whole time he was talking of Dante, Tolomei was putting out his two fingers again and touching the wood of his chair.

‘There, that’s where you’ll be, my lord,’ he went on, making a mark in his big book; ‘immediately after Monseigneur de Marigny; but be reassured, not the one who was hanged and whom Monseigneur of Artois mentioned a little while ago. No, his brother, the Bishop of Beauvais. From today you have a credit with me of ten thousand livres. You can draw on it at your convenience, and look on my modest house as your own. Cloth, arms, jewels, you will find every kind of goods you may require at my counters and can charge them against this credit.’

He was carrying on his trade by habit; lending people the wherewithal to buy what he sold.

‘And what about your lawsuit against your aunt, Monseigneur? Are you thinking of taking it up again, now that you’re so powerful?’ he asked Robert of Artois.

‘I most certainly shall, but at the right time,’ the giant replied, getting to his feet. ‘There’s no hurry, and I’ve learnt that too much haste is a bad thing. I’m letting my dear aunt grow older; I’m leaving her to exhaust herself in small lawsuits against her vassals, make new enemies every day by her chicanery, and put her castles, which I treated a bit roughly on my last visit to her lands – which are really mine – into order again. She’s beginning to realize what it costs her to hold on to my property. She had to lend Monseigneur of Valois fifty thousand livres which she’ll never see again, for they went to make up my wife’s dowry, and incidentally enabled me to pay you off. So, you see, she’s not quite so noxious a woman as people say, the bitch! I merely take care not to see too much of her, she’s so fond of me she might spoil me with one of those sweet dishes from which so many people in her entourage have died. But I shall have my county, banker, I shall have it, you can be sure of that. And on that day, as I’ve promised you, you shall become my treasurer.’

Messer Tolomei showed his visitors out, walking down the stairs behind them with some prudence, and accompanied them to the door that gave on to the Rue des Lombards. When Roger Mortimer asked him what interest he was charging on the money he was lending him, the banker waved the question aside.

‘Merely do me the pleasure,’ he said, ‘of coming up to see me when you have business with the bank. I am sure there is much in which you can instruct me, my lord.’

A smile accompanied the words, and the left eyelid rose a little to reveal a brief glance that implied: ‘We’ll talk alone, not in front of blabbers.’

The cold November wind blowing in from the street made the old man shiver a little. Then, as soon as the door was closed, Tolomei went behind his counters into a little waiting-room where he found Boccaccio, the travelling representative of the Bardi Company.

‘Friend Boccaccio,’ he said, ‘today and tomorrow buy all the English, Dutch and Spanish currency you can, all the Italian florins, doubloons, ducats, and foreign money you can find; offer a denier, even two deniers, above the present rate of exchange. Within three days they’ll have increased in value by a quarter. Every traveller will have to come to us for foreign currency, since they’ll be forbidden to export French gold. I’ll go halves with you on the profits.’

Having a pretty good idea of how much foreign gold was available and adding it to what he already had in his coffers, Tolomei calculated that the operation would make him a profit of from fifteen to twenty thousand livres. He had just lent ten thousand and would therefore make about double his loan. With the profits he could make further loans. Mere routine.

When Boccaccio congratulated him on his ability and, turning the compliment in his thin-lipped, bourgeois, Florentine way, said that it was not in vain that the Lombard companies in Paris had chosen Messer Spinello Tolomei for their Captain-General, the old man replied: ‘Oh, after fifty years in the business, I no longer deserve any credit for it; it’s simply second nature. If I were really clever, do you know what I would have done? I’d have bought up your reserves of florins and kept all the profit for myself. But when you come to think of it, what use would it be to me? You’ll learn, Boccaccio, you’re still very young …’

Boccaccio had sons who were already grey at the temples.

‘You reach an age when you have a feeling of working to no purpose if you’re merely working for yourself. I miss my nephew. And yet his difficulties are more or less resolved; I’m sure that he’d be running no risk if he came back now. But that young devil of a Guccio refuses to come; he’s being stubborn, from pride I think. And, in the evening, when the clerks have left and the servants gone to bed, this big house seems very empty. I sometimes regret Siena.’

‘Your nephew ought to have done what I did, Spinello,’ said Boccaccio, ‘when I found myself in a similar difficulty with a woman of Paris. I removed my son and took him to Italy.’

Messer Tolomei shook his head and thought how melancholy a house was without children. Guccio’s son must be seven by now; and Tolomei had never seen him. The mother refused to allow it.

The banker rubbed his right leg which felt heavy and cold; he had pins and needles in it. Over the years, death began to catch up with you, little by little, taking you by the feet. Presently, before going to bed, he would send for a basin of hot water and put his leg in it.

4 (#ulink_b95e41d3-bc20-5ce5-8518-8ba87888f6f2)

The False Crusade (#ulink_b95e41d3-bc20-5ce5-8518-8ba87888f6f2)

‘MONSEIGNEUR OF MORTIMER, I shall have great need of brave and gallant knights such as you for my crusade,’ declared Charles of Valois. ‘You will think me very vain to say my crusade when in truth it is Our Lord’s, but I must confess, and everyone will recognize the fact, that if this vast enterprise, the greatest and most glorious to which the Christian nations can be summoned, takes place, it will be because I shall have organized it with my own hands. And so, Monseigneur of Mortimer, I ask you straight out, and with that frankness you will learn to recognize as natural to me: will you join me?’

Roger Mortimer sat up straight in his chair; he frowned a little and lowered his lids over his flint-coloured eyes. Was he being merely offered the command of a banner of twenty knights, like some little country noble or some soldier of fortune stranded here by the mischances of fate? The proposal was mere charity.

It was the first time Mortimer had been received by the Count of Valois, who till now had always been busy with his duties in Council, or receiving foreign ambassadors, or travelling about the kingdom. But now, at last, Mortimer was face to face with the man who ruled France, who had that very day appointed one of his protégés, Jean de Cherchemont, as the new Chancellor,

and on whom his own fate depended. For Mortimer’s situation, undoubtedly enviable for a man who had been condemned to prison for life, though painful for a great lord, was that of an exile who had nothing to offer and was reduced to begging and hoping.

The interview was taking place in what had once been the King of Sicily’s palace, which Charles of Valois had received from his first father-in-law, Charles the Lame of Naples, as a wedding present. There were some dozen people in the great audience chamber, equerries, courtiers, secretaries, all talking quietly in little groups, frequently turning their eyes towards their master, who was giving audience, like a real sovereign, seated on a sort of throne surmounted by a canopy. Monseigneur of Valois was dressed in a long indoor robe of blue velvet, embroidered with lilies and capital V’s, which parted in front to show a fur lining. His hands were laden with rings; he wore his private seal, which was carved from a precious stone, hanging from his belt by a gold chain; and on his head was a velvet cap of maintenance held in place by a chased circlet of gold, a sort of undress crown. Among his entourage were his eldest son, Philippe of Valois, a strapping fellow with a long nose, who was leaning on the back of the throne, and his son-in-law, Robert of Artois, who was sitting on a stool, his huge red-leather boots stretched out in front of him. A tree-trunk was burning on the hearth near by.

‘Monseigneur,’ Mortimer said slowly, ‘if the help of a man who is first among the barons of the Welsh Marches, who has governed the Kingdom of Ireland and has commanded in a number of battles, can be of help to you, I willingly give you my aid in defence of Christianity, and my blood is at your service from this moment.’

Valois realized that here was a proud man, who spoke of his fiefs in the Marches as if he still held them, and that he must treat him tactfully if he wished to make use of him.

‘I have the honour, my lord,’ he replied, ‘to see arrayed under the banner of the King of France, or rather mine, since it has been arranged that my nephew shall continue to govern the kingdom while I command the crusade, to see arrayed, I say, the leading sovereign princes of Europe: my cousin Jean of Luxemburg, King of Bohemia, my brother-in-law Robert of Naples and Sicily, my cousin Alfonso of Spain, as well as the Republics of Genoa and Venice who, at the Holy Father’s request, will give us the support of their galleys. You will be in no bad company, my lord, and I shall see to it that everyone gives you the respect and honour due to the great lord you are. France, from which your ancestors sprung and which gave birth to your mother, will make sure that your deserts are better recognized than they appear to be in England.’

Mortimer bowed in silence. Whatever this assurance might be worth, he would see that it came to more than mere words.

‘For it is fifty years and more,’ went on Monseigneur of Valois, ‘since anything of importance was done by Europe in the service of God; to be precise, since my grandfather Saint Louis who, if he won his way to Heaven by it, lost his life in the process. Encouraged by our absence, the Infidels have raised their heads and believe themselves masters everywhere; they ravage the coasts, pillage ships, hinder trade and, by their mere presence, profane the Holy Places. And what have we done? Year after year we have retreated from all our possessions and establishments; we have abandoned the castles we built and have neglected to defend the sacred rights we had acquired. And this has all happened as a result of the suppression of the Templars, of which my elder brother – peace to his soul, though in this I never approved him – was the instrument. But those times are past. At the beginning of this year, delegates from Lesser Armenia came to ask our help against the Turks. I give grateful thanks to my nephew, King Charles IV, for his understanding of the importance of this appeal and for giving his support to the steps I then took. Indeed, he now believes the idea to have been originally his. Anyway, it is most satisfactory that he should now have faith in it. And so, as soon as our own forces have been assembled, we shall go to attack the Saracens in their distant lands.’

Robert of Artois, who was listening to this speech for the hundredth time, nodded his head as if much impressed, while secretly amused at the enthusiasm his father-in-law displayed in explaining the greatness of his cause. Robert was well aware of what lay behind all this. He knew that, though it was indeed the intention to attack the Turks, the Christians were to be jostled a little on the way; for the Emperor Andronicos Paleologos, who reigned in Byzantium, was not so far as one knew the champion of Mahomet. No doubt his Church was not altogether the true one, and it made the sign of the Cross a bit askew; nevertheless, it did make the sign of the Cross. But Monseigneur of Valois was still pursuing his idea of reconstructing to his own advantage the fabulous Empire of Constantinople, which extended not only over the Byzantine territories, but over Cyprus, Rhodes, Armenia, and all the old kingdoms of the Courtenays and the Lusignans. And when Count Charles arrived there with all his banners, Andronicos Paleologos, from what one heard, would not be able to put up much of a defence. Monseigneur of Valois’s head was full of the dreams of a Caesar.