По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

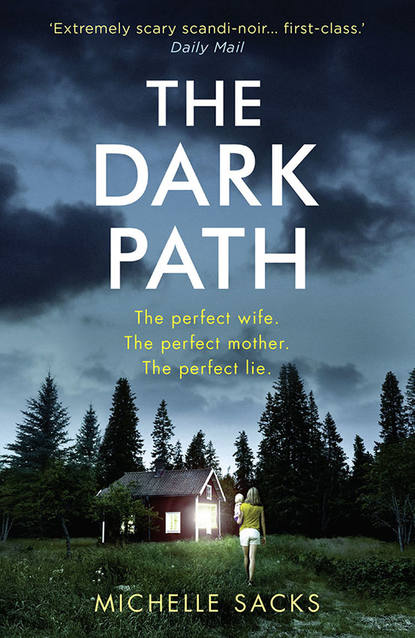

The Dark Path: The dark, shocking thriller that everyone is talking about

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

I sipped an espresso from a mint green cup.

This is great, the creative director commented, very dynamic.

I reckon I have a fresh perspective, I said. With my background.

It wasn’t so difficult, all this self-promotion. Fake it till you make it and all.

It says here you taught at Columbia?

Yes, I said.

Why the career change?

I gave a wry smile. Well, after enough years teaching young people, you realize you’ve got it in reverse. They know it all and you’re just a dinosaur with a piece of chalk.

Oh, and I was fired. I guess I could have added that.

They laughed. A good answer. Endearing, not too cocky. I’ve got it down to an art.

So you did a lot of filmmaking as an anthropologist?

Some, yes. Mostly in the early days of my career, the time I spent doing fieldwork in Africa. But film was always what I really wanted to do. That’s why I’ve returned to documentary now.

They looked at me and I smiled. Not one of them a day over thirty, and all of them so effortlessly self-possessed you’d think they were Fortune 500 CEOs.

Snow tires. The shoot is for a company that makes snow tires.

Great, I said. Sounds interesting.

A mobile phone rang and the producer got up to take the call. Before he left the room, he slipped a business card onto the table in front of me.

Sorry, the creative director said, we’re busy with a big project at the moment; everyone’s a little distracted.

It was my cue to leave. I shut my laptop and stood up, knocking the chair back as I did.

He shook my hand. We’ll let you know.

How was your meeting? Merry asked when I got back home.

It was good, I said, really good.

She beamed. Wonderful.

She had Conor in her arms, freshly bathed and ready for bed.

His eyes were red, like he’d been crying.

Did you two have a good day? I asked.

Oh, for sure, she said. The best.

Merry (#ulink_b338684c-4fc4-52d8-91b1-ab5cfdf0dbc2)

Domestic chores aren’t usually Sam’s department, but last night he volunteered to bathe the baby. He emerged from the bathroom afterward holding him in a towel.

Hey, he said, what’s this over here?

He lifted the towel and showed me the child’s thighs. My face flushed. I had not noticed the marks, four little blue bruises against his skin.

That is strange, I said. I swallowed.

I wonder, Sam said, could his clothes be too tight? Could that be it?

Yes, I said, more than likely. I should have bought him the next size up by now.

Sam nodded. Well, you should take care of that in the morning.

Absolutely, I said, first thing.

And so, in the name of new baby clothes, I was permitted the car for today. Sam took the baby and I headed into Stockholm, music blaring, windows open to the warm midsummer air. Exhilarating, the heady feeling of freedom, of leaving the island behind. I had dressed up, a light floral summer skirt, a sleeveless blouse.

In Stockholm, I parked the car and checked my face in the mirror. I loosened my hair and shook it out. I painted on mascara and lined my lips with color. Transformed. I walked a short way to a café in Södermalm I’d read about.

Sometimes I do this, page through travel magazines and imagine all the alternative lives I might be living. Drinks at the newest gin bar in Barcelona, a night in Rome’s best boutique hotel.

I picked up an English newspaper from the counter and sat at a table by the window, pretending to read. I love to peoplewatch in the city. Everyone is so beautiful. Clear skin and bright eyes, hair shining, bodies taut and well proportioned. There is no excess. Nothing bulging out or hanging over or straining at the seams. Even their clothes seem immune to crumpling. It isn’t just Karl and Elsa next door: it’s a whole country of them.

Immaculate Elsa. I should probably invite her over for fika, try to make friends. We could discuss pie recipes and childrearing; I might ask her about her skincare routine. Only I’ve never been very good at it. Female friendships. Well, apart from Frank, I suppose.

Sam keeps asking if I’m excited for her visit. I try to be enthusiastic. I do look forward to it, I think. Showing off our lives, showing her everything I have accomplished. Showing her who is ahead.

But there is another part of me that feels deep unease. Something about the way Frank always sees more than she should. She likes to think she knows me better than anyone – maybe even myself. She considers this a triumph. So she pokes at my life like a child with a stick, prodding at a dead seal washed up on the shore. Waiting to see what crawls out. Peekaboo, I see you!

She is always digging, digging, trying to go beyond the surface. The real you, she says, I know the real Merry. Whatever that means.

At the table across from me, I watched a young woman. She must have been in her early twenties, blond and slim and well dressed. She was eating a cinnamon bun, forking small bites of pastry into her mouth. She kept brushing a finger gently to her lips. She talked with an older man, perhaps in his forties, dressed in a gray cashmere sweater and dark jeans. Like me, he watched her movements closely, followed her fork with his eyes into her mouth; followed her fingers as they danced on those red lips. At one point she touched his arm, casual and friendly and innocent of all desire, but for him I could see it was electrifying.

She was showing him something on a laptop screen, pointing with her long fingers. She wore no wedding band, just a thin gold ring on her index finger, set with a small topaz stone in the center. He nodded intently as she spoke; she wrote something down in a notebook that lay open next to her cup. He watched her take a sip, the way she licked her lips to make sure that no foam lingered. Love or infatuation, who could ever tell.

An older woman walked in alone, ordered a coffee and a sandwich from the barista, and sat down at a table near the window. She was flawless. White trousers, neat leather pumps, pearl earrings. She must have been sixty or more, glowing and beautiful, without anything surgically pulled or plumped. It is a mystery here, how their women are permitted to age with such grace.

I thought of my own mother, her freakish final face and all the ones in between. So many years she spent obsessively trying to ward off the inevitabilities of aging. Every few months, something new. Eyes ironed out at the corners, extra skin pulled back and sewn high into the temples. Fatty deposits sucked out and reassigned, either to cheeks or lips. Breasts lifted, stomach fat suctioned through a pump.

As a child, I loved to watch her getting herself ready to go out. My father was always coming home with invitations to galas and balls; charity dinners or openings of new wings at the hospital. It was an elaborate performance, painting on a face, torturing her hair into some elegant updo, squeezing into a dress two sizes too small and two decades too young.

You’re so pretty, I’d say.

I’m not pretty enough, she always replied.