По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

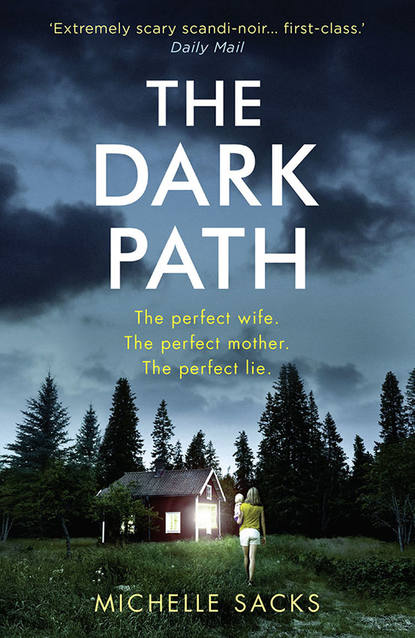

The Dark Path: The dark, shocking thriller that everyone is talking about

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

After we said our goodbyes, I closed the door and pulled Merry to me.

That was fun, I said.

Yes, she said.

Aren’t they like wax models, those two?

Yes, she said. Elsa is flawless.

I made a mental note to take Karl up on his offer to go hunting, while Merry went to finish the last of the cleaning up, packing dishes into the dishwasher, wiping down the countertops, gathering the crumbs into her hand.

I lifted Conor off the rug and into my arms. He smelled of Elsa’s perfume. And shit.

I handed him over to Merry. Looks like it’s time for a diaper change, I said.

Merry (#ulink_28739f8a-132c-5039-84b9-858c9e20256e)

I watch the baby through the bars of his crib. A little prison, to keep him safely inside. He watches me. He does not smile. I do not bring him joy.

Well. The feeling is mutual.

I look at his face. I watch closely for signs of change. They tell you that they transform all the time. They are supposed to resemble their father first, then their mother, then back again. But he is only me. All me. Too much of me.

His eyes stare, a constant reproach. Accusatory. Remember, they say, remember what you have done. I’m sorry, I whisper, and look away.

My bars are not bars. They are glass and trees. The glass cage that is our house, the huge glass windows all around that Ida’s father installed to maximize light and space. The ancient tall pines that block off the light. My island exile, all escapes closed off, all outside life shut out. Just us.

Sam and me and the baby.

All we need, Sam says.

Is it? I say. Doesn’t it feel like we’re the last three survivors of a plane crash?

Oh … He laughs at my silliness.

He was off in Stockholm or Uppsala today – I forget which – playing his show reel for ad executives and producers. He is trying hard to make this work. He really is doing his best. He always does. Family, he says: nothing matters more. This is why we moved here, a new start, the very best place to raise a family. How he loves the baby. How he adores every part of him and every little thing he does. Once, he looked at me like this, as though I were a wonder of nature, a rare being to worship and adore.

Ba-ba. Ma-ma. Pa-pa.

Everything we say is broken into two syllables.

Bird-ee.

Hors-ee.

Hous-ie.

The baby eats some of the time but not always. Often I make him food and eat it myself, letting him watch as I spoon it into my mouth.

See? No mess.

I offer him the spoon and he shakes his head.

The baby cries a lot but forms no words. He rocks on his belly but does not yet know how to crawl. There are milestones that I am surely supposed to be checking and am not. The copy Sam bought me of The Ultimate Guide to Baby’s First Year lies unopened next to the bed, under a tube of organic rose hand cream that sends five percent of its profits to the preservation of the rain forest.

You read it, right?

Of course, I lie. It was terrifically informative.

The baby. My baby. He has a name, but somehow I can’t bring myself to say it out loud. Conor Jacob Hurley. Naturally, Sam named him. Conor Jacob, he said, Jacob after his best friend from high school who was lost at sea on a round-the-world sailing trip. Conor in deference to Sam’s vaguely Irish roots. Conor Jacob. Conor Jacob Hurley. It was decided, written down on the tag on his tiny wrist. I read it. I mouthed the words of my son’s name. Conor Jacob Hurley.

The balloons next to the hospital bed were baby blue. One had already burst, its deflated remains drifting forlornly among the rest.

Would you like to hold your son? the nurse offered.

If Sam was out of the room, I would shake my head.

He believes I am a good mother, the very best kind. Devoted and all-nurturing and selfless. Without a self. Perhaps he is right about the last part. Sometimes I wonder myself: Where am I? Or: Was there anyone there to begin with?

The days Sam isn’t home always feel like a vacation. The baby and I have no audience to impress. Usually, I don’t shower. I don’t change out of my nightgown. I sit on the couch watching reality TV, my dirty little habit (one of many, I should add). I cannot get enough. Plastic women devouring each other, housewives and teen mothers. How they play at being real, when really it’s all for the cameras. Still, everyone pretends not to know. The conspiracy is a success.

Most days, I eat wedges of butter to stave off my sugar cravings and keep my weight down, but when Sam’s away, I unpack my hidden stash from the barrel of the washing machine and indulge in whole bags of crisps and cookies, which I smuggle home from the grocery store under packs of diapers and organic detergent. I am vile. Terrifically unladylike. I pick at my toenails and squeeze out the ingrown hairs from my legs. Sam would shudder if ever he saw me like this. Sometimes I shudder myself, at this version of me. Well, she will need to be banished once Frank arrives. There will be no such escapes for a while.

Some days, I think it would be nice to go out, to leave our little island territory, but of course Sam has the car. It’s an hour on foot to get anywhere from here, and forty minutes’ walk to the nearest bus station. Sam bought himself a mountain bike for the trails, but it’s been ruled out for me. Too dangerous, he said, with a baby.

That leaves us stuck. Just us. Mother and child, with nothing to do but revel in domestic duties. I suspect Sam likes it. No, I know he does. My lack of distraction. My utter focus. Actually, it surprises me how encouraging he’s being about Frank’s visit. In New York, I was always hearing complaints about any outside interests or distractions. The parts of me that weren’t entirely consumed with Sam. Sam’s favorite music, Sam’s current reading list, Sam’s teaching materials, his new eating habits, or his latest workout. Sam’s everything. And now Sam’s baby.

The baby. The baby we made. The baby we let into the world. I remember how I felt that day, standing in the pokey beige bathroom of our apartment which always smelled of the deep fryer from the Indian restaurant downstairs, looking at the two lines faint on the stick, the lines of life, imminent and incontrovertible. It was the second test. Whoopsie daisy. A whoopsie baby.

The door burst open, Sam home early and unexpectedly.

Is that? he asked, looking at me, caught red-handed. I did not miss a beat. Yes, Sam, I cried. Isn’t it the very best news.

The origin of the word suffer is “to bear.” You are not supposed to overcome it. You are only supposed to endure. I am free to leave, this is what anyone would say to me, but the question is how, and with what, and to where. These have never been questions I could answer. They have never seemed like my decisions to make. In this world, I have no one but Sam. He knows this. It is surely part of the allure. That and how I am no good on my own. I would not know where to begin.

There are sleepless nights and nights that don’t end. I wake sometimes and find the baby in my arms, yet I have no recollection of fetching him. He screams himself awake and I go to his crib, watching him turn red and fuming, tears streaming down his face, cries catching violently in his throat. Feral, raging changeling from the wild. I am reluctant to pick him up, loath to offer him comfort, even though this is all he wants from me, all he asks. I cannot give it. I can only stand and watch, silent and unmoving, until he is all cried out and too exhausted for more.

Sleep training, I’ll explain to Sam, if he complains about the crying. I’ll quote a reputable pediatric authority, because I like to show him how seriously I take our child’s development. Still, he’ll find things to point out that I am doing wrong. He’ll offer wisdom and advice – minor improvements, he calls them, and there’s always room for these. Yes. He does love to educate me. He is very good at it. Filling in the blanks. I think perhaps he considers me to be one of the blanks, too, and slowly he is filling me in. Do this, wear that. Now you should quit your job. Now we should marry. Now we should breed.

Over the years he has shown me what to appreciate and what to disavow. Italian opera, classical Russian pianists. Experimental jazz. Korean food. French wine.

Is it Dvořák? I ask him, as though I don’t know. As though I wasn’t the one raised in the oceanfront house in Santa Monica, lavished with education and private lessons beyond anything I wanted or deserved.

Husband. Hūsbonda. Master of the house.

I suppose he only tells me things I don’t know myself. What I need. What I want. Who I am. And in return for this, I give it my all. I give Sam the exact woman he wants me to be. A faultless performance. Nothing else would do.

The men before Sam wanted to rescue me, kiss away the boo-boos. Sam wanted to make me over from scratch. And I hate to disappoint him, because disappointing Sam is the worst feeling in the world. It is the end of the world, actually, and the return of the hopeless, relentless, gnawing vacancy inside.