По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

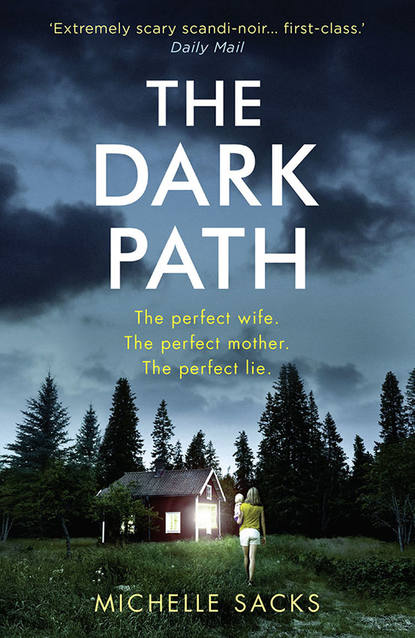

The Dark Path: The dark, shocking thriller that everyone is talking about

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Or sometimes: I used to be, before you came along.

There were many things for which I was accused and held accountable. The loss of her figure. The thinning of her hair. The sagging of her skin. The absence of my father’s attention.

He never told her to stop the surgeries. Perhaps this was how he punished her.

Sam likes me natural, he says. This means slim. Groomed. Depilated. Scrubbed and lotioned, smooth like a piece of ripe fruit.

He shaved me once, early on in our relationship; made me stand over him in the bath while he took a razor between my legs and slowly carved away. There, he said, that’s how I want you.

I had looked down at my new self with delight. Beloved, I thought, this is what it feels like to be beloved.

Six years in and still, in the early hours of the morning, while Sam lies and dreams, I clean my teeth and shine my face and comb my hair. I shape my eyebrows and tint my lashes and pluck away the stray hairs that plant themselves on my upper lip; I trim my cuticles and buff the dead skin from my heels, I paint my nails to match the seasons. I shave and moisturize and soften my skin, I spray perfume and roll deodorant and use special intimate wipes to make me smell like flowers instead of a woman. All this I do so that when he wakes, I am transformed, when he wants me, I am ready. All yours, I say. I am all yours.

It is a lie; a small part I keep for myself.

It must have been around noon when I realized I was hungry. I left the café and strolled around the cobbled back streets in the glare of the sun. It’s a pleasant city, I suppose. Charming, contained in a way that New York is not, and never can be. Here there is none of that current in the air, the pulse of lust and need and ruthlessness. Of longing and secrets.

Around Götgatan I spied a café with a neat little row of quiches sitting in the window. I went inside and ordered at the counter, sat down at a small table in the corner. The waitress brought over my food and laid down cutlery and a napkin. Tack, I said, and she smiled sweetly. The quiche was delicate, not too heavy. It felt strange and delicious to eat alone; a forbidden delight from another life.

I ordered a coffee after I finished, not wanting it to end just yet. The café was filling up with people; I saw the waitress glance over at me. She came up to the table.

Would you mind? she said. This man would like to eat something.

It was the same man from earlier.

May I? He indicated the free chair opposite me.

I smiled. Of course.

You are American, he said, as he sat.

Yes, I said. Sorry about that.

He laughed. I tried to recall the movements of the woman from earlier, the way she touched her lips, delicate and deliberate. I brushed my fingers against my mouth. I watched him watch me.

What are you doing here, he said, business or pleasure?

Oh. I smiled. Always pleasure.

Again my fingers went to my lips.

You remind me of someone, he said.

Yes, I said, I hear that all the time.

You’re on vacation? he asked.

I hesitated. There was something I had to take care of here, I said.

I wanted to sound enigmatic and mysterious. The kind of woman a man like him aches for. I took a sip of coffee, I touched my lips. I smiled sadly and looked suddenly toward the street, into the middle distance, as though recalling some dark secret or heartache within.

Yes, I had it. I watched him watch me and shift in his seat.

In New York, there were countless days like this. It’s easy in a city that size. You never see the same person twice. Never have to be the same person. Sitting in the park, strolling through the Met, whiling away a few hours in the public library. I was the woman in the red dress, or the blue coat, or the scarf with red lips printed all across it. I was a lawyer, a grad student, a midwife, an anthropologist, a gallerist; I was Dominique or Anna or Lena or Francesca. I was all of these women. Everyone but Merry. It was always a rush, a moment belonging only to me; a spectacle for my own entertainment. My own secret pleasure. Only occasionally did it go too far.

Even as a child, I loved nothing better than to perform in front of the bathroom mirror. Sometimes I’d steal one of my mother’s lipsticks or some of her jewelry. I’d pretend to be a model or an actress, sometimes a lovesick girlfriend or a wife betrayed. I liked to watch myself, the transformation into someone else. I’d try out different voices and accents, different expressions on my face. I could play out scenes for hours on end. It never grew dull. It still doesn’t. Perhaps this is my gift. The ability to slip in and out of selves, as though they were dresses hanging in a wardrobe, waiting to be tried on and twirled about.

I’m Lars, by the way, the man said.

He extended his hand and I let it linger in mine. While he ate his lunch, I entertained him with stories from my recent trip to the Maldives.

Can you imagine, I laughed, two weeks on a tropical island with only the winter wardrobe of Mr. Oleg Karpalov in my possession!

Which island? he asked.

I tried to recall Frank’s email and couldn’t. I glanced at my watch.

I have to go, I said.

He grabbed my wrist.

Wait, he said. Give me your number.

He took his phone from his pocket and wrote down the digits I offered.

I smiled.

I had won.

It was late and I had to hurry to Drottninggatan to find a department store. I needed to be Merry again. In the baby section, I threw piles of clothes over my arm. T-shirts, miniature chinos, cargo shorts with dinosaurs on the pockets, little track pants and pajama bottoms.

The phone rang and my heart sank.

Where are you? Sam asked. I thought you’d be back by now. He sounded irritated.

I apologized profusely. I had a hard time finding what I was looking for, I explained. You know I always get lost here, in the city.

Well, come back soon, he said.

Yes, Sam, I said, apologizing once more before I hung up the phone.

I paid for the baby clothes and slipped into the restroom. In front of the mirror, I wet a wad of paper and wiped off the remnants of my makeup under the bright white light. Inside one of the stalls, a woman was retching. Probably an eating disorder, I thought, though it could have been anything.

I made my way back to the car and did find myself lost – the cobbled lanes, the tasteful storefronts, the quaint boutiques and antiques shops – all of them blend into the same tepid view: spotless streets, polite pedestrians, the too-orderly flow of people and traffic. The heady freedom of earlier was already in retreat. My chest was constricting, the streets narrowing in parallel, closing me in, squeezing it all back down to size. I hate to upset Sam. It fills me with terror, any time he has a reason to find me lacking.

At last I found the parking lot. An old Roma woman sat begging at the entrance. She looked at me, sucked her teeth, and wagged a finger. A witch casting a curse.

I drove home too fast. When I got back, Sam handed me the baby.