По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

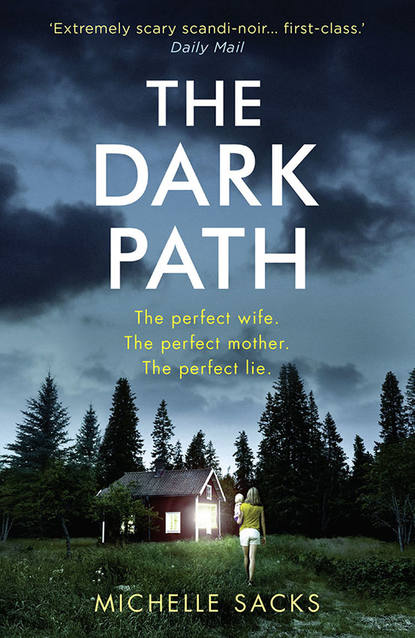

The Dark Path: The dark, shocking thriller that everyone is talking about

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

He’s good like that. Proactive. I admire that quality in a person, the ability to decide and do, to set plans in motion. It has never been something I’m particularly good at. I often wonder what my life might look like if I was.

On my knees in the bathroom, I started with the bath. Scrubbing and shining the taps till I could see myself reflected back, distorted and inverted, pulling our week of collective shed hair out of the drain in a single swampy ball. The toilet next, finicky work, head in the bowl. What would my mother say if she could see me now? In the mirror, I looked at myself. Unkempt, that’s what my mother would say. Or, more likely, hideous. Unwashed, no makeup, skin slicked in oil. A thin trickle of sweat pooling down my T-shirt. I sniffed under my armpits.

Then I smiled into the mirror, dazzling and wide. I opened my arms in a gesture of gracious welcome.

Welcome to our home, I said aloud. Welcome to our lives.

The woman in the mirror looked happy. Convincing.

There was a phone call earlier this morning from Frank. She woke the baby.

I’m coming to Sweden, she said.

What?

I’m coming to visit!

I’ve said it to her again and again in the year we’ve been here, at the end of every email and phone call. You must visit, it’s wonderful; we’d love to have you.

And now she is coming. She will be here in a few weeks.

Your best friend, Sam said when I told him. That’s great news.

Yes, isn’t it, I said, smiling.

I’d emailed her just a few days ago. Another missive about my wonderful Swedish life, with photographs as proof. Something home-baked, a smiling child, a shirtless husband. She replied almost immediately, informing me of her new promotion, a sparkling new penthouse in Battersea. She attached a photograph of herself from a recent break to the Maldives. Frank in a pineapple-print bikini, sun-kissed and oiled, the lapping Indian Ocean in the background, a coconut cocktail in her hand.

I wonder what she’ll make of all this. The picture of my life, when she sees it in the flesh.

I wiped the mirror and opened the windows to air the room of the stench of vinegar. In the kitchen, I moved the dishwasher and cleaned the dirt gathered against the wall. I scoured the oven of fat and grease, climbed up on the ladder to clean the top of the refrigerator. Sometimes I like to carve out messages in the dust. HELP, I wrote this morning, for no particular reason.

The baby woke up and began to cry just as I was halfway through bottling the last of the excess vegetables in brine. Pickling is another of my newfound skills. It’s very rewarding. I went into the baby’s room and stared at him in his crib.

Boiling over, face red with rage at his neglect. Spit foaming out of his mouth as he cried. He saw me and frowned, held out his arms, rocked on his haunches to try to propel himself up and out.

I watched him. With all my heart, I tried to summon it. Please, I thought, please.

Instincts, they call them, but for me they are the very furthest thing. Buried somewhere deep inside under too many layers, or altogether missing.

Please, I urged again, I coaxed, I begged. But inside, like always, there was only emptiness. Cold and hollow. The great void within.

I could do nothing but stand and watch.

The baby’s cries grew more urgent, his face twisted with hot and vicious need. Almost purple. I stood helpless, rooted to the spot. I turned my head away so he would stop appealing to my eyes, imploring me to alleviate his rage. Unable to comprehend that I could not do it.

I looked around his room, filled with books and stuffed toys. A map of the world on the wall, along with stenciled illustrations of Arctic mammals. Polar bear. Moose. Fox. Wolf. I’d done it myself, the last month of pregnancy, balancing a paint box on the mound of my belly. The whole world, just for him. And still it is not enough. I am not enough.

And he is too much.

In the noise, I tried to find my breath, to feel the beating of my heart. It was pounding today, loud with upsets of its own; an angry fist in a cage.

I edged closer to the crib and peered down at the hysterical child. My child. I shook my head.

I’m sorry, I said at last. Mommy is not in the mood.

I left the room and closed the door behind me.

Sam (#ulink_d9d72f63-6384-5f40-98f0-f049f6d50bb8)

Karl and I sat outside while the women finished up the salads in the kitchen. He and his wife, Elsa, are our neighbors from across the field, good solid Swedes, wholesome and hardworking. She’s in adult education; he runs a start-up that converts heating systems into more energy-efficient models. They invited us to their midsummer party last year right after we moved in, and this is how long it’s taken us to have them over.

New baby, I apologized, and Karl shrugged. Of course.

Their daughter, Freja, was sitting on the lawn playing with Conor. Karl and I were talking, and I was trying not to stare at him too intently. It’s hard to look away. His startling blue eyes, the height and spread of him. A full-blooded Viking. He’d brought over a gift of vacuum-sealed elk meat.

You’ll have to join me for a hunt one day, he said. All the Swedes do it.

So, remind me, Karl said, what is it you do.

I shifted. I’m trying to get into film, I said. Documentary film.

You were doing that before?

No, I said. Before, I was an academic. Associate professor of anthropology. Columbia University.

He raised his eyebrows. Interesting. What was your area of study?

I smiled. The transformative masks of ritual and ceremony in West Africa, particularly the Ivory Coast. How’s that for useless information?

It’s very interesting, I’m sure.

It was, actually. The masks are fascinating, I said. The way they enable such fluidity of identity and power in these tribes, the way they depend on masking and performance for their—

I stopped myself from continuing. From remembering what

I missed.

Onward, onward and up.

Anyway, it was time for a change, I said.

I finished the last of the beer in my glass, thought back to the final meeting with that brittle spinster Nicole from Human Resources. Sign here, initial this. A swift and unceremonious dismissal that took almost two decades of work – all the successes and accolades and titles – and vanished it into the ether.

But they haven’t even heard my side, I said.

They know more than enough already, she replied coolly.

So you moved here for a new job, Karl said.