По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

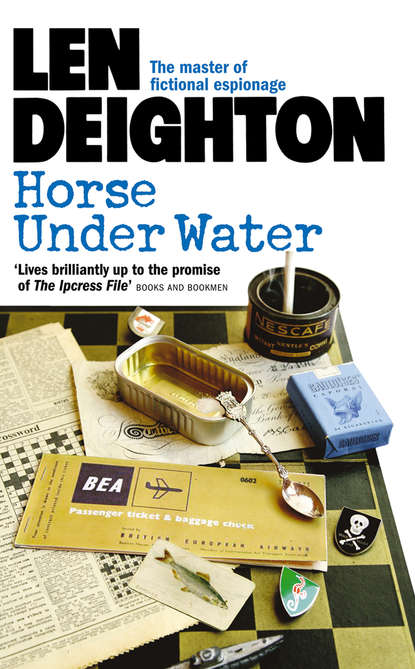

Horse Under Water

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Security, old chap, don’t want those career-mad Admiralty people to know all our little secrets.’

I nodded. ‘Look,’ I said, ‘I’ll need your signature if I am to draw a pistol from War Office armoury.’ There was a long silence, broken only by the sound of Dawlish blinking.

‘Pistol?’ said Dawlish. ‘Are you going out of your mind?’

‘Just into my second childhood,’ I said.

‘That’s right,’ said Dawlish, ‘they are nasty, noisy, dangerous toys. How would I feel if you jammed your finger in the mechanism or something?’

I picked up the air ticket and underwater-gear inventory and walked to the door.

‘West London 9.40,’ he said; ‘try to have the Strutton report ready before you leave, and …’ He removed his glasses and began to polish them carefully. ‘You have a pistol of your own that I am not supposed to know about. Don’t take it with you, there’s a good chap.’

‘Not a chance,’ I said, ‘I can’t afford the ammunition.’

That day I completed my report for the Cabinet on the Strutton Plan. The plan was to have a new espionage network of people feeding information back to London. All of them would be telephone, cable, telex operators or repair engineers working in embassies or foreign government departments. It meant setting up employment agencies abroad which would specialize in this type of employee. As well as describing the new idea my report had to outline the operations side, i.e. planning, communications, cut-outs,

post boxes

and a superimposed system

and, most important as far as the Cabinet report was concerned, costing.

Jean finished typing the report by 8.30 p.m. I locked it into the steel ‘out’ box, switched on the infra-red burglar-alarm system and set the special phone system to ‘record’. Next door was our telephone exchange: Ghost, used in the same way that the Government used Federal exchange. Anyone dialling one of our numbers by mistake heard about a minute and a half of the ‘number obtainable’ signal before it began ringing. After that the night operators next door challenged the caller, then our phone rang. There were advantages; I could for instance call a number on Ghost from any phone and have the operator connect me to anywhere in the world without attracting attention.

Jean put the typewriter ribbons into the safe. We said good night to George the night man and I put my tickets for B.E.A. 062 into my overcoat.

Jean told me about the carpet she’d bought for her flat and promised to fix me dinner when I returned. I told her not to leave the Strutton Plan report with O’Brien, suggested at least three different excuses she could give him, and promised to look out for a green suede jacket in Spain, size 36.

6 Ugly rock (#ulink_ab3ccea2-791e-5ba3-9e64-c3854dc4dae5)

The airport bus dredged through the sludge of traffic as sodium-arc lamps jaundiced our way towards Slough. Cold passengers clasped their five-shilling tickets and one or two tried to read newspapers in the glimmer. Cars flicked lights, shook their woolly dollies at us and flashed by, followed by ghost cars of white spray.

At the airport everything was closed and half the lighting switched off to save the cost of the electricity we had paid seven and six airport tax for. A long thin line of passengers shuffled down the centre of the draughty customs hall while Immigration men snapped passports in their faces with impartial xenophobia. In the lounge a blonde with smudged mascara played us a gay tune on her teeth with a ballpoint pen before we were sealed into the big, shiny, aluminium pod.

Sitting near the front of the aircraft was a plump man in a plastic raincoat. His red face was familiar to me and I tried to remember in what connexion. He was bellowing loudly about the air conditioning.

The surrounding airport was twittering with Klee-like coloured lights and signs. Inside the cabin the strongest had fought for and won their window seats, sick bags were ready and cabin temperature control set at ‘Roast’. Starters whined, dipped the cabin lights to half strength and heaved at the propeller blades. The big motors pounded the wet air, settled into a roar and dragged us up the black ramp of night.

The automatic pilot took control; white plastic cups danced and shuddered across the little stage clipped before me, shedding plastic spoons and large wrapped sugar segments.

I could see the back of the plump man’s head. He was shouting. I tried to remember everyone who had been involved in the ice-melting file transaction, and wondered if Dawlish had checked this passenger list.

Eight thousand feet. Beneath us green veins of street-lighting X-rayed Weymouth on to the night. Then only the dark sea.

Thin damp triangles of bread clung helpless across the pliable plate. I ate one. The steward poured hot coffee from the battered metal pots in appreciation. Constellations of city lights merged with icicles of stars suspended in the cavern of the sky.

I dozed until – Plonk Plonk – the undercarriage came down and cabin lighting was turned fully bright to open sleep-moted eyes. As the plane rumbled to a halt anxious holidaymakers clasped last year’s straw hats and groped towards the exit door.

‘Goodnightsirandthankyou … goodnightsirandthankyou … goodnightsirandthankyou …’ The stewardess bestowed a low communion upon departing passengers.

The plump man edged his way along the plane towards me. ‘Number 24,’ he said.

‘What?’ I said nervously.

‘You are number 24,’ he said loudly. ‘I never forget a face.’

‘Who are you?’ I asked.

His face bent into a rueful smile. ‘You know who I am,’ he shouted. ‘You are the man in flat number twenty-four and I am Charlie the milkman.’

‘Oh yes,’ I said weakly. It was the milkman with the deaf horse. ‘Have a good holiday, Charlie. I’ll settle up when you get back.’

‘Coaches for Costa del Sol,’ the loudspeakers were saying. The Customs and Immigration gave a perfunctory sleepy nod and stamped ‘30 days’ on the passport.

I could see a square, solid, British figure fighting through the Costa del Sols. ‘Welcome to Gibraltar,’ said Joe MacIntosh, our man in Iberia.

7 Short talk (#ulink_c393107d-e0a1-5f62-bd63-3b8b43f97efa)

Joe MacIntosh drove me out to one of the married-officer accommodations along Europa Road past the military hospital. It was 3.45 a.m. The streets were almost empty. Two sailors in white were vomiting their agonizing way to the Wharf and another was sitting on the pavement near Queen’s Hotel.

‘Blood, vomit and alcohol,’ I said to Joe, ‘it should be on the coat of arms.’

‘It’s on just about everything else,’ he said sourly.

After we’d had a drink Joe promised to brief me in the morning before he went on ahead. I slept.

We had breakfast in the mess and the water supply wasn’t quite as salty as I remembered it. Joe filled in some of the details.

‘We have been hearing about this counterfeit paper money for some years; it’s being washed up out of the sea.’

I nodded.

‘I’ve made a little sketch map.’

Joe opened his wallet and pulled out a page of a school exercise book. On it was drawn a shaky tracing of the south-western quarter of the Iberian peninsula. The Straits of Gibraltar were in the bottom right-hand corner. Lisbon was near the top left. Small mapping-pen crosses had been inked in along the coastline. The 100-kilometre stretch between Sagres (on the extreme south-western tip) and Faro curved, in a 100-kilometre-long bay. Trapped into the curve like bubbles were most of Joe’s little marks.

Joe began to tell me the arrangements he had made. ‘The nearest town to the wreck is Albufeira, here …’ Joe hadn’t changed much from the tall, muscular, Intelligence Corps lieutenant who came to Lisbon as my assistant in 1942. ‘… This is a list of all the wrecks that have happened between Sagres and Huelva and …’ Scores of young Intelligence Officers came to Lisbon in ’41 and ’42, all anxious to spend one strenuous week bringing the Axis to its knees. Mostly they fell prey to the simplest little security traps we set or they got into arguments with Germans in cafés. We hooked their new boys and they hooked ours, and old timers (anyone who had spent more than three months there) exchanged sardonic smiles with their enemy opposite number over thimbles of black coffee. ‘… using an Italian civilian frogman with whom I have worked before. He is perhaps the best frogman in Europe today. If you stop overnight in the town I have marked I’ll phone him to meet you there. Code word: conversation. I’ll be going by another route.’

‘Joe,’ I said. Through the window I could just see Mount Hacho on the North African mainland across the clear air and sunny water of the Straits. ‘What have you been told about this operation?’

Joe slowly brought a packet of cigarettes from his pocket, took one and offered them.

‘No thanks,’ I said. He lit his own and then put away his matches. His hands moved very slowly but I knew his mind was working like lightning.

He said, ‘You know the Wren with the rather large …’

‘I know the one,’ I said.