По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

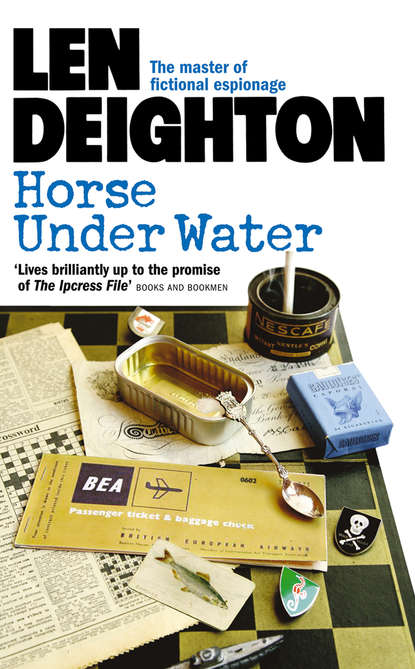

Horse Under Water

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘The MS 29 is a fine echo-recorder system. I work with her before. I tell you, is a big big U-boat. You will see.’

I certainly hoped it would all become clearer to me.

‘Yes,’ I said, ‘I will see.’ Ahead I could see the roofs of Ayamonte, in the Sector de Sevilla entrusted to Brigada MCVIL.

The River Guadiana forms the frontier between Spain and Portugal. Splashed along its Spanish bank is the little white cubist town of Ayamonte.

I let the car roll down a cobbled side street until the slow-moving river lay in front. I turned and drove along the quayside, negotiating the litter of nets, broken packing-cases and rusty oil-drums. Señor Olivettini produced a U.N. passport and we both went into the tired old building that houses the officials. They looked at our passports and stamped them. On the wall was a vignetted photo of a dark-shirted officer. It was signed in a big looping signature and dated a year before the outbreak of the civil war. One man looked inside the car and I was worried about the pistol. That was just the sort of thing that would cause Dawlish to do his nut. The guard said something to Giorgio and hitched his automatic rifle higher on his shoulder. Giorgio spoke rapidly in Spanish and the brittle face of the guard splintered into loud laughter. By the time I reached the car the guard was inhaling on one of Giorgio’s cheroots.

I drove down the sloping jetty on to a splintered boat. The weight of the car strained the ropes on the hand-made bollard and the water sagged under the burden. The boat grumbled across the oily grey water as the little white buildings floated slowly away. Getting the car on to the land of Portugal is a job for at least twelve helpers, all shouting ‘Back, left-hand down, a bit more,’ etc., in fluent Portuguese. I told Giorgio to get out and make sure they had the narrow planks correctly placed under the wheels. I wasn’t keen to learn the Portuguese for ‘too far’. The car wasn’t square on the boat, and as the rear wheels rolled on to them, one of the planks shot away like a bullet. I let the clutch right in and punched the acceleration. The car leapt forward and hurtled up the steep corrugated ramp like ten thimbles across a washboard. I waited for Giorgio. He walked up the ramp smacking imaginary dust from his impeccable trousers. He looked into the window of the car, his hands nervously engaged in twisting his gold rings. He smiled briefly, took his small, new briefcase from under his arm and put it into the car. I hadn’t noticed him remove it.

‘Valuable,’ he said.

Portugal is a semi-tropical land; cared-for, cultivated, and geometrical. This is not Spain, with leather-hatted civil guards brandishing their nicely oiled automatic rifles every few scorched yards. It’s a subtle land, without sign of Salazar on poster or postage stamp.

‘What about equipment?’ I said. ‘If you are going to look at this submarine do you think you can operate in forty metres?’

‘The first, Mr MacIntosh is bringing for me; the second, yes, I can operate in forty metres. I will use compressed air, it is simple. I am a great expert in the underwater working. Sixty metres I could do.’

The westbound Estrada Principal Numero 125 out of Loule continues the descent the road has been making since S. Braz. A small police-truck hooted twice and sped past us. The road south from this junction leads only to the fishing town of Albufeira; we turned left and headed past the canning factory.

Albufeira is a town built on a ramp. The streets slope steeply uphill and the sound of low gears engaging is constantly heard. The houses that lie along the top of the ramp have their white backs inset into the top of eighty-foot cliffs.

Number 12 Praca Miguel Bombarda is one of the few houses that have private steps leading down to the beach. From the large patio at the rear of the house one can see a couple of hundred yards to the west, and the other way perhaps two miles to Cape Santa Maria, where at night the lighthouse flashes. From the front of the house the little low window – set as deep as a cupboard into the thick stone wall – looks across a triangle of cobbled space at a bent tree and an upright lamp-post. As I parked the car under the tree Joe MacIntosh looked out of the door. The church bell was striking 9 p.m. Thursday.

The night air pressed its damp nose to the window pane. Ocean sand and water were thrashing together in endless permutations, and somewhere in the depths beyond was the sunken wreck that had brought us here.

11 Help (#ulink_5bf11687-5946-5442-8c7b-7a6a496749f5)

On Friday morning an old black Citroën came down from the embassy in Lisbon. Driving it was a clean-cut fair-haired lad, wearing knee-length shorts and a cream Aertex shirt. He knocked at the door. I answered.

‘Lieutenant Clive Singleton. Assistant Naval Attaché, British Embassy, Lisbon.’

‘O.K.,’ I said, ‘no need to use a loud hailer, I’m only eighteen inches away. What’s biting them?’

‘My information is for the ears of your Commandant.’

‘I’ve got news for you, Errol Flynn, I’m my own Commandant. Now weigh anchor and cast off.’ I began to close the door.

‘Look here, sir, here,’ he said through the crack, his big blue eyes wet with anxiety. ‘It’s about the …’ He paused and hissed the word ‘sub’. By now the door was so nearly closed that he was playing it like a woodwind. ‘You must retrieve the log book.’

‘Come in.’

I let him into the tiled hallway. Enough light filtered through the two thicknesses of lace curtain for me to take stock of him. About twenty-six, lank fair hair, wiry figure, five foot eleven, leather sandals, blue Austin Reed socks, a black document case with a crest on it. This boy was blue-blazer-with-a-badge-on-it material.

‘O.K.,’ I said, ‘you’re in – what’s your message?’

He spoke very rapidly. ‘I’m seconded to work with you, sir, on account of my skin-diving experience. I’ve brought my equipment in the car … .’

‘I can see you have,’ I said. Sitting in the car was a young blonde.

‘Yes sir.’ He ran his hand through his hair and smiled nervously. ‘Charlotte Lucas-Mountford – Admiral Lucas-Mountford’s daughter.’ I said nothing. ‘London told us that we should send someone with underwater experience and someone to look after the household. Charlotte speaks fluent Portuguese and I have the …’

I closed the door and slowed him to a standstill with my eyes. I took a long time lighting a cigarette and I didn’t offer them.

‘Sit down, sonny,’ I said, ‘sit down and dust off your mind. You think you’re on a ripping little fun-jaunt, don’t you?’

‘I’m a Clearance Diver, sir, R.N. certificate. You’ll need an underwater expert for this job.’

‘I will, will I?’ I said. ‘Well, I don’t know what you call “expert”, but the man we already recruited spent nearly four years as an Italian frogman. He once spent a night standing in pitch darkness on the floor of Gibraltar Harbour mending a timing device while the Navy threw every grenade they could find into the harbour. They only stopped in the morning because they calculated no one could be alive down there. Then he swam up under the North Mole, fixed a charge weighing 550 lb. to a tanker and swam back to Algeciras. He did that twenty years ago when you were wearing a Mickey Mouse gas-mask and saving your coupons for a Mars bar. If you are going to work here there’s not going to be any half-way for ladies and it’ll mean being a lot smarter than you’ve been so far. Why do you think London sent that message in code to the embassy? Why do you think Lisbon couldn’t send me a wire? They trusted you with it because they wanted to make sure it didn’t get intercepted, and yet as soon as I bend a little muscle at you you broadcast it.’ I waved down his explanations. ‘Go and get your equipment,’ I said.

Giorgio made some quiet remarks about Clive’s bright-green undersea gear, but it was much more professional than I feared it might be. As for Charlotte, I’d never seen her before, but there were two things about her one could never forget. However, she set to work in the kitchen in a way that surprised me. They were both dying to prove how efficient and tough they were.

After breakfast we had a conference. Joe spread the linen Admiralty charts across the table and showed us the way the U-boat was lying. The echo-sounder charts were strips of electrolytic paper about seven inches wide. Down each was a thick black uneven band (the ocean floor) and a thin black uneven band, separated by a quarter-inch of white. The thinner of the two bands was fish or objects lying along the ocean floor. On one chart a shape could be interpreted. I was prepared to take an expert’s word that it resembled a U-boat.

According to Singleton, Naval Intelligence were very keen to get the log of the U-boat as it was of a new type about which they had very little information. I asked Giorgio and Joe what the chances were.

Joe said, ‘If the log wasn’t dumped overboard before the sub. sank, it’s easy.’

‘You know where to find the log book? I can ask London about stowage procedures.’

Giorgio said, ‘It will not, I think, prove necessary. I have encountered some experience of the life aboard the German craft.’ We exchanged thin grins.

‘And if they did jettison it?’

‘In that case it depends upon: one,’ Giorgio tapped his index finger, ‘how far the boat traversed between the jettison and sinking, and two, if the Kelvin Hughes apparatus will encounter such a small flat objective which will likely submerge into the mud, and three,’ the gold ring on his finger flashed in the bright sunlight, ‘if the boat has been moved much distance by means of the underwater currents which I suspect are strong.’

After that Giorgio asked Joe about tidal movement at surface, absolute slack-water times and slack-water duration, and they discussed ways of setting out a diving timetable in order to use those facts to advantage.

Charlotte brought in a large tin pot of coffee and a plate of black figs. She said, ‘After I’ve drunk my coffee I’ll go and do the bedroom.’ There was a moment or two in which we were all alone with our thoughts.

There was no point in getting the boat into position so late in the day. I told everyone to relax that afternoon, we’d have another briefing that night and go out on the morning tide for a reconnaissance.

Dawlish had cleverly realized that the way to prevent someone deserting from a situation was to put him in charge of it.

The sea was kicking idly at the beach that Friday afternoon. Charlotte was nearly inside a white bathing suit, Giorgio was doing handstands that had her oo-ing and clapping her brittle little hands together, and Singleton was jumping in and out of the water like a yo-yo. I told Giorgio to swim out to sea with Singleton and let me know what sort of endurance he had.

‘Go out about two hundred and fifty yards and come in again. Don’t hurry him, but let him know you’re watching him.’

‘Yes, it is understood,’ said Giorgio, and went to tell Singleton.

I watched them run across the soft damp sand lengthening the curved imprints that marry space and time in huge dotted arabesques. Then Joe talked about the echo-sounder.

‘I put the sounder in when we first got a whisper of this job three – no, nearly four – weeks ago; we’ve used it for fishing ever since. It’s deadly efficient and some of the fishermen have been talking about buying them for themselves.’

‘Isn’t there a possibility that they’ll follow us out to locate the fish?’

‘No, I disconnected it yesterday and I told the old man to say it had gone wrong.’ He paused, carefully designing a sentence that wouldn’t sound impertinent. ‘Why doesn’t London do this operation through official channels – and get local cooperation?’