По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

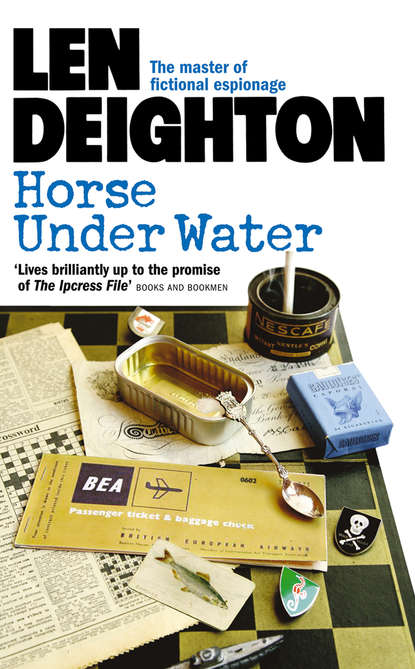

Horse Under Water

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘She’s the cipher clerk,’ Joe said. ‘I was chatting her up the other day when I noticed a clip-board with carbons of all the messages I’ve sent from here to London over the last two months. They all had BXJ in the corner. I’d never heard of that priority before, so I asked her what it was.’ He dragged on the cigarette. ‘They are sending all our signals traffic to somebody in London for analysis.’ Joe looked at me quizzically.

‘Who?’ I said.

‘She’s only the clerk,’ Joe said, ‘it’s the signals officer that redirects them, but she …’ He tailed off.

‘Go on.’

‘She’s not sure.’

‘So she’s not sure.’

‘But she thinks it goes to somebody c/o the House of Commons.’

I signalled for some more coffee and the Spanish waitress brought us a big jug. ‘Have some coffee,’ I said, ‘and relax; it’ll all work out.’

He gave me a shy Li’l Abner smile. ‘I wanted to tell you,’ he said, ‘but it sounds so unlikely.’ We went down to Andalusian Cars in City Mill Lane to pick up a grey Vauxhall Victor for me and a Simca for Joe. He started out for Albufeira and would be there before evening. I had some things to attend to in Gibraltar and my journey would be in two hops.

It was still the same squalid town that I remembered from wartime. Huge barrack-like bars with everything breakable long since removed or broken. Accordion music and drunken singing, red-necked military policemen bullying fat soldiers, thin-lipped army wives weaving among the avaricious Indian shopkeepers on the sun-bright pavement. The secret of enjoying Gibraltar, a ship’s doctor had once told me, is not to get off the boat.

8 I hit it (#ulink_c595d339-29d3-5fb1-90a2-1a856edf9a0e)

Wednesday morning

The end of Gibraltar’s High Street is Spain. Grey-suited frontier guards nodded, looked for transistor radios and watches, then nodded again. I drove through a couple of hundred yards of dead ground, then through the second control post. The road winds back through Algeciras, and looking across Algeciras Bay one sees the whole of Gib. lying there like a wedge of stale cheese; from the heights where the apes stare down to the airport, to the south where the Ponta de Europa drops away to the sea.

After Algeciras the road began to climb. At first it was dry as burnt toast, but soon white steamy cloud twined through the wheels or sat in heaps on the quiet road. To the left a cliff top was as jagged as a picnic tin. The road descended and followed the beaches northward. It was 3 p.m. The sky was as blue as the Wilton diptych and the warm air drew the smog from my lungs.

Sucking nourishment from the Seville highway, Los Palacios is a huge, gangling village that would be a town if it could afford the paving stones. Great loops of underpowered electric bulbs stared fish-eyed into the twilight as I drove in. One café had a new Seat

1400 outside it. The name EL DESEMBARCO was painted in gaunt letters, deep set into the dark doorway. I put my foot softly on to the brake. A big diesel lorry hooted behind me as I pulled off the roadway. The lorry parked too and the driver and his mate went inside. I locked up and followed.

There were about thirty customers in one huge barn-like room. Smoked hams and bottles were strung across the walls, and large mirrors with gold advertisements hung from the wall and gave curious sloping dimensions to the reflected drinkers. A glittering Espresso machine roared and pounded. On the black matt counter-top bills were chalked and computed by boys with damp white faces who darted between the gigantic barrels, stopping only to wring out their aprons in gestures of despair, and shout plaintive entreaties to the kitchen in high waiters’ Spanish that cut through the clouds of smoke and talk.

I girded up my conversation.

‘Deme un vaso de cerveza,’ and the waiter brought me a bottle of beer, a glass and a small oval plate of freshly boiled shrimps, moist and delicious. I asked him about rooms. He slipped his white apron over his head and hung it on a hook under the Jayne Mansfield calendar. I hate to think what it might have been advertising. The boy led me out through the rear door. To my right I saw the flare of the kitchen and caught the piquant smell of Spanish olive oil. It was almost dark.

There was a sandy courtyard at the back, partly covered with bamboo from which hung rusting neon lights. Down one side of the courtyard a glassed-in stone corridor gave access to small, cell-like rooms. I negotiated a pram and a Lambretta motor scooter and entered my room. It contained an iron bedstead with crisp clean sheets, a table and a cupboard for a chamber-pot.

‘Veinte y cinco – precios fijos si v gusta,’ said the waiter. A fixed price of twenty-five pesetas seemed O.K. to me. I dumped my overnight bag, gave a Gauloise to the waiter, lit both our cigarettes and went back to the noisy restaurant.

The waiters were serving wine, coffee, sherry, and beer as fast as they could go – putting a squirt of soda into a glass from a distance of two feet, slamming down little plates of smoked ham, salt biscuits or shrimps, arguing with the drunks while adroitly serving the sober. The big tent of sound throbbed against the rafters and hammered down again.

All through the fish soup and omelette I waited for my contact. I asked who owned the new car outside. The boss owned it. I had more Tio Pepes and watched the lorry driver who had hooted me doing a card trick. At 10.30 I wandered out front. Three men in overalls sat on the unpaved ground drinking from a flagon of red wine, two children without shoes were throwing stones at the big diesel truck and some men were arguing quietly about the market value of a used motor-cycle tyre.

I unlocked the door of the car and reached under the dashboard for the .38 Smith & Wesson hammerless 6-shot. The grips were powerful magnets. I pulled it away from the car body, folded it into the car documents, locked up and walked back to my room.

My overnight bag still had my used match lying on it, but before going to sleep I opened the little cupboard and put my gun under the chamber-pot.

9 I sit on it (#ulink_e02ea630-6a16-5bc5-a074-41901b07a5d7)

The sun was scorching the courtyard in which I took Thursday’s breakfast. Potted geraniums surrounded the well, and pink convolvulus climbed along the bamboo roofing. Half concealed by the limp washing, a large pockmarked Coca-Cola advert was bleached faint pink by the sun, and the church tower from which nine dull clanks came was toylike in the distance.

‘A friend of Mr MacIntosh, is it not, yes?’

Standing beyond my tin pot of coffee was a squat muscular man, about five feet six. His head was wide, his hair dark and waved. His face was tanned enough to emphasize the whiteness of his smile. He carried his arms in front of his body and continually plucked at his shirt cuffs. He flicked his fingers across a large area of green silk pocket-handkerchief and tapped three fingers of his right hand against his forehead with an audible tap.

‘I have the message for you which your friend request I should deliver in person.’

His manner of speaking had a strange, jerky rhythm and his voice seldom became lower at the end of each sentence, which led one to expect a few more words to appear any moment. ‘Conversion,’ he said. I knew that the real code word was ‘conversation’.

He reached inside his short pin-stripe jacket and produced a hide wallet as lumpy as a razor blade, and from it slid a business card. He replaced the wallet, smoothed his dark shirt, ran fingers slowly down his silver tie. His hands were short-fingered, powerful, and curiously pale. He offered me the card from his carefully manicured hand. I read it.

S. Giorgio Olivettini

Underwater Surveyor

MILAN VENICE

I shook the card a couple of times and he sat down.

‘You had breakfast?’

‘Thank you, I have already consumed breakfast, you permit?’

Señor Olivettini had produced a small packet of cigars. I nodded and shook my head at appropriate intervals and he lit one up and put the rest back into his pocket. ‘Conversation,’ he said suddenly, and gave a vast smile. He seemed to be my passenger to Albufeira.

I went into my room, put the gun into my trouser pocket, picked up my bag and fixed the bill. Señor Olivettini was waiting by the Victor polishing his two-tone shoes with a bright yellow duster.

For about thirty kilometres I drove in silence and Señor Olivettini smoked and contentedly filed and buffed his nails.

My pistol had worked its way under my thigh. It was an uncomfortable thing to sit on. I let the car lose speed.

‘You have planned to stop?’ said Señor Olivettini.

‘Yes, I am sitting on my gun,’ I said. Señor Olivettini smiled politely. ‘I know,’ he said.

10 Sort of boat (#ulink_54cadaf2-deff-5eb0-a939-574a5ea5f21b)

This was Giorgio Olivettini, the man who had thrown Gibraltar into a panic during the war when as an Italian naval frogman he had operated across Algeciras Bay from a secret base in an old ship.

‘We are to take cargo from a U-boat, huh?’ Giorgio asked.

‘Not a U-boat,’ I corrected gently.

‘Oh yes,’ said Giorgio confidently. ‘Your Mr Joe MacIntosh send me Kelvin Hughes echo-charts of the wreck. She is a U-boat.’

‘You’re sure?’ I asked.