По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

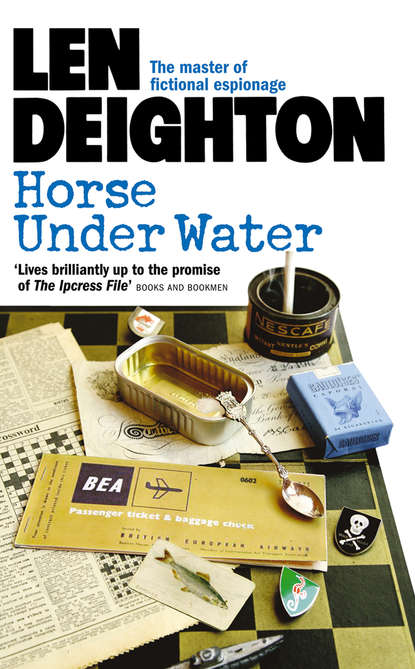

Horse Under Water

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Dawlish was a tall, grey-haired civil servant with eyes like the far end of a long tunnel. Dawlish always tended to placate other departments when they asked us to do something difficult or stupid. I saw each job in terms of the people who would have to do the dirty work. That’s the way I saw this job, but Dawlish was my master.

On the small, antique writing-desk that Dawlish had brought with him when he took over the department – W.O.O.C.(P) – was a bundle of papers tied with the pink ribbon of officialdom. He riffled quickly through them. ‘This Portuguese revolutionary movement …’ Dawlish began; he paused.

‘Vós não vedes,’ I supplied.

‘Yes, V.N.V. – that’s “they do not see”, isn’t it?’

‘“Vós” is the same as “vous” in French,’ I said; ‘it’s “you do not see”.’

‘Quite so,’ said Dawlish, ‘well this V.N.V. want the F.O. to put up quite a lump sum of money in advance.’

‘Yes,’ I said, ‘that’s the trouble with easy payment plans.’

Dawlish said, ‘Suppose we could do it for nothing.’ I didn’t answer. He went on, ‘Off the coast of Portugal there is a boat full of money. It’s money that the Nazis counterfeited during the war. English and American paper money.’

I said, ‘Then the idea is that the V.N.V. boys get the money from the sunken boat and use it to finance their revolution?’

‘Not quite,’ said Dawlish. He probed the hot pipe-embers with a match. ‘The idea is that we get the money from the sunken boat for them.’

‘Oh no!’ I said. ‘You surely haven’t agreed to that. What do F.O. Intelligence Unit

get paid for?’

‘I sometimes wonder,’ agreed Dawlish, ‘but I suppose the F.O. have their troubles too.’

‘Don’t tell me about them,’ I said, ‘it might break me up emotionally.’

Dawlish nodded, removed his spectacles and dabbed at his dark eye-sockets with a crisp handkerchief. Behind him on the window ledge the sun was rolling dusty documents into brandy snaps.

In the street below a man with a twin horn was dissatisfied with the existing disposition of traffic.

‘V.N.V. say that off the Portuguese coast there is a wrecked ship.’

Dawlish could never tell you anything without drawing a diagram. He drew a small formalized ship on the notepad with a gold pencil. ‘It was a German naval vessel en route to South America in March 1945. Inside it there is a considerable amount of excellent counterfeit currency, sterling five-pound notes, fifty-dollar bills and some genuine Swedish stuff. It was for high-ranking Nazis seeking exile, of course.’ I said nothing. Dawlish dabbed his eyes and I heard the traffic outside begin to move again.

‘The V.N.V. want us to help them retrieve these items. For “help them retrieve” you can read “present them with”. F.O. see this as a way of supporting what they think is an inevitable change of power, without implicating us too deeply, or costing any money. Comment?’

I said, ‘You mean the Portuguese revolutionaries are to use the counterfeit U.S. money and the genuine Swedish stuff to buy guns and generally finance a political Paul Jones, but the English money they can’t use because the design of the fiver has been changed.’

‘Quite so,’ said Dawlish.

I said, ‘I’m cynical. Do you have the name of the ship, charted position of the wreck and German bills of lading from Admiralty Historical Department?’

‘Not yet,’ said Dawlish, ‘but I have confirmed that there have been a fair number of counterfeit fivers in that region. They may have come from a wreck. Also V.N.V. have a local fisherman who is confident about locating it.’

‘Item 2,’ I continued, ‘the idea is that we mount a subversive operation in Portugal, which is a dictatorship whichever side of the dispatch box you rest your feet. This in itself is a tricky enterprise, but we are going to do it, in cooperation with, or on behalf of, this group of citizens whose openly avowed aim it is to overthrow the government. This you tell me is going to cause H.M.G. less embarrassment than planting a few hundred thousand into a bank account for them.’

Dawlish pulled a face.

‘O.K.,’ I said, ‘so don’t let’s have any false ideas about motivation. It’s a way of saving money at a considerable risk – our risk. I can see the working of the P.S.T.’s

eager little mind. He is going to organize a revolution while the Americans have to finance it because there are so many counterfeit dollars turning up all over the world. But Treasury are wrong.’

Dawlish looked up sharply and began tapping his pencil on the desk diary. The twin horn had nearly reached Oxford Street. ‘You think so?’ he said.

‘I know so,’ I told him. ‘These Portuguese characters are tough guys. They have been around. They will get rid of the British stuff all right, then the Treasury will be all long faces and little pink memos.’

We sat in silence for a few minutes while Dawlish drew a choppy sea above his drawing of a boat. He swivelled his chair round so that he could see through the dingy windows, jutted his lower lip forward and beat it with his pencil. In between this he said ‘Ummm’ four times.

He turned his back to me and began to speak. ‘Six months ago O’Brien told me that he knew of one hundred and fifty experts on world currency. He said there were seven who knew all the answers about moving it, but when it came to moving and changing it illegally, O’Brien said that you would be his choice every time.’

‘I’m flattered,’ I said.

‘Perhaps,’ said Dawlish, who considered illegal talent a dubious virtue; ‘but Treasury may have second thoughts, if they know how strongly you are against it.’

‘Don’t sell tickets on the strength of it,’ I told him. ‘What F.S.T.

will pass up a chance of saving perhaps a million pounds sterling? He probably has the College of Heralds designing a coat of arms already.’

I was right. Within ten days I had a letter telling me to report to the R.N. Instructional Diving School (Shallow Dive Course No. 549) at H.M.S. Vernon. The F.S.T. was going to get an earldom and I would get an Admiralty diving certificate. As Dawlish said when I complained, ‘But you are the obvious choice, old boy.’ He inscribed the numeral ‘one’ on his notepad and said, ‘One, Lisbon 1940, many contacts, you speak a bit of the lingo. Two,’ he wrote ‘two’, ‘currency expert. Three,’ he wrote ‘three’, ‘you were in on the first contacts with the V.N.V. in Morocco last month.’

‘But do I have to go on this frogman course?’ I asked. ‘It will be wet and cold and it’ll all take place in the early hours of the morning.’

‘Physical comfort is just a state of mind, my boy, it will make you fighting fit; and besides,’ Dawlish leaned forward confidentially, ‘you’ll be in charge, you know, and you don’t want these blighters nipping below for a crafty smoke.’ Dawlish then uttered a curious polyphonic sound, rather high-pitched at first, ending in a vibrating palate and terminated by the distribution of tobacco ash throughout the room. I stared incredulously; Dawlish had laughed.

3 Undersea need (#ulink_fb5e30d3-c559-54fc-8ea5-092ad017588e)

There is a point on the A3 near Cosham at which the whole of Portsmouth Harbour comes suddenly into view. This expanse of inland water is a vast grey triangle pointing to the Solent. The edges are sharp serrated patterns of docks, jetties and hards enclosing the colourless water.

A penetrating drizzle had been leaking through the low cloud since I had joined the A3 at Kingston Vale about 6.45 a.m. Window display men were junking polystyrene Xmas trees and ordering gambolling lambs. On their way to work people were sneaking a look at shop windows to see how much their relatives had paid for the presents they had received.

The snow had been around a long time. Layer upon layer had crystallized and hardened into abstract shapes. Now it sat like a delinquent child glaring at passers-by and daring them to try moving it. The ground had absorbed so much cold that rain made a slippery layer on the ice. I slowed as crowds of factory and dockyard workers swarmed across the streets. I turned into the red-brick gate of H.M.S. Vernon. A rating stood there in oilskins that gleamed like patent leather. He waved me to a halt. I walked to the porch where half a dozen sailors in damp saggy raincoats sat huddled together, hands in pockets. From the brittle Tannoy came a message for the duty watch. I knocked at the counter.

A young rating looked up from the assorted parts of a bicycle bell that lay before him on the table.

‘Can I help you sir?’

‘Instructional Diving Section,’ I said.

He asked the operator for a number and sat, eye-glazed, waiting to be connected. On the notice board I read about the Q.M. of the watch being responsible for boilers when there were men in cells. Under it hung a copper bugle with highly polished dents. I signed into the visitors’ ledger ‘Time of arrival 08.05’, a drip of rain spattered on to the page. Inside the office were the highly polished lino and blancoed belts that go with military police systems everywhere in the world. A two-badge seaman took over the phone and clobbered the receiver rest a few times. A P.O. emerged, holding a brown enamel teapot. He looked at my Admiralty authority.

‘That’s all right – take him over to Diving.’ He disappeared still holding the teapot in both hands.

The rain hammered the concrete roadways and paths and large freshly painted ships’ figureheads dribbled pensively. The Instructional Diving Section was a barn-like building that echoed to the noise of metal drums being moved. Behind a wire screen was a hardboard counter and a muscular rating.

‘Course 549?’ he asked.

‘Yes,’ I said. He eyed my civilian raincoat doubtfully. Over the Tannoy came the clang of one bell in the forenoon watch. A tall one-stripe hooky exchanged a Gauloise cigarette for half a cup of dark brown tea and I warmed my hands on the enamel sides of the mug. I knew it would all take place in the early hours of the morning.