По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

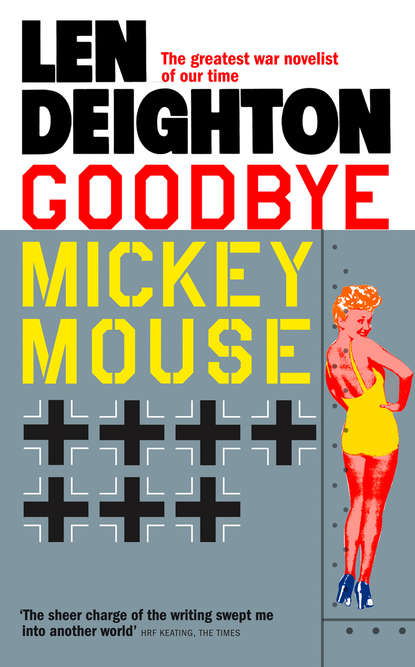

Goodbye Mickey Mouse

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘You’ve got something there, pal.’ MM turned in his seat for a better view of the RAF men. ‘One of the topkicks asked the Limeys to stick around. There’s some kind of celebration in the Rocker Club tonight.’

‘And?’

‘They want to grab some gas and get back to their squadron. Look at those kids, will you? Are we going to look like that by the time we are home again?’

‘Did you hear the radio this morning? The RAF lost thirty heavy bombers over Germany last night. Thirty crews! Sure they want to get back, to see if their buddies made it.’

Lieutenant Morse got to his feet and said, ‘I’m going into Cambridge on my motorcycle, want to come?’ Morse’s black mongrel, Winston, crawled out from under the table and shook itself.

‘I’ve got some letters to write.’

‘So can you lend me five pounds?’ MM drained his coffee cup while standing up. Farebrother passed him the money and MM nodded his thanks. ‘So they went to Berlin last night,’ he said enviously. ‘You get headlines going to Berlin. No one wants to know about the flak at Hannover or the fighter defences at Kassel. But go to Berlin and you’re a headline.’

‘And you want to be a headline?’

‘You bet your ass I do. A kid at school with me was on a sub that sank a Jap ship. The town gave him a parade. A parade! He was a hashslinger on a pigboat. He never even finished high school.’

The Officers’ Club bar was a gloomy place, most of the blackout shutters permanently fixed over the windows. Farebrother found a corner of the lounge, and despite the noise of the men fixing up the Christmas tree in the hallway, he began writing a letter to his mother.

‘Can I get you a drink, sir?’ It was one of the British waiters, a completely bald, wizened man, bent like a stick and flushed with that shiny red skin that makes even the most dyspeptic of men look jolly.

‘I don’t think so,’ said Farebrother.

‘You won’t be flying today, sir,’ he coaxed. ‘The rain is turning to sleet.’ Farebrother looked up to see wet snow sliding down the window glass fast enough to obscure the view across the balding lawns to the tennis courts. Over the loudspeakers came a big-band version of ‘Jingle Bells’ on a damaged record that clicked.

‘It’s too early for booze, Curly. The captain wants a cup of coffee.’ It was Captain Madigan—Farebrother recognized him from the night journey on the truck from London. ‘None of that powdered crap, real coffee, and a slice of that fruitcake you sons of bitches all keep for yourselves back there.’

The bald waiter smiled. ‘Anything for you, Captain Madigan. Two real coffees and two slices of special fruitcake, coming right up.’

Madigan didn’t sit down immediately. He threw his cap onto the window ledge and went across to warm himself at the open fire. When he turned round he kept his hands behind him in a stance he’d learned from the British. ‘My God, but this must be the most uncomfortable place in the world.’

‘Have you tried the Aleutians or the South Pacific?’

‘Don’t deny a man his right to grouse, Farebrother, or I’ll start thinking you’re some kind of Pollyanna.’ He bent over to remove the cycle clips from his wet trousers. ‘I suppose you’re sleeping in a steam-heated room here in the club?’

‘I’m in one of the houses across the road.’

‘Well, buddy, I’m in one of the tents that blew down last night. There’s clothing and stuff scattered over three fields. The mud’s ankle deep in places.’

‘There’s a spare bed in my room.’

‘Whose?’

‘Lieutenant Hart.’

‘The one who was shot down over Holland?’

‘Lieutenant Morse told me Hart had an ulcer.’

Madigan looked at him for a moment before replying. ‘Then let’s keep it an ulcer.’

‘I don’t get it.’

‘Lieutenant Morse isn’t really a fighter pilot,’ said Madigan. ‘He’s a movie star, playing the role of fighter pilot in this billion-dollar movie Eisenhower is producing.’

‘You mean he doesn’t like talking about casualties?’

Before Madigan could reply the loudspeaker was putting out a call for the Duty Officer.

Farebrother said, ‘It’s room 3 in house number 11. Dump your things in there and wait till you’re kicked out. That’s what I would do.’

Madigan slapped Farebrother on the shoulder. ‘Farebrother, you are not only the greatest pilot since Daedalus, you’re a prince!’ Madigan repeated this to the waiter when he arrived with the coffee and cake. ‘I’m sure you’re right, Captain Madigan,’ said the waiter. ‘And thanks for the toy planes.’

‘Aircraft-recognition models,’ Madigan explained when the old man had gone. ‘What do I need them for in the PR office. He’s giving a party for the village children next week.’

‘You’re a regular Robin Hood,’ said Farebrother. He gave up the attempt to write to his mother and began to drink his coffee.

Madigan remained standing, searching his pockets anxiously as if he was looking for something to give Farebrother. ‘Look,’ he said as he relinquished the search. ‘I can’t find my notebook right now, but you haven’t made any plans for Christmas, have you?’

‘I figured we might be flying.’

‘Even the sparrows will be walking, Farebrother. Look at that stuff out there. You don’t need to have majored in science to know that the Eighth Air Force birdmen are going to be having a drunken Christmas.’

‘And what about the public relations officers? What kind of Christmas are they going to be having?’

‘London is a dump,’ said Madigan, sitting down on the sofa and giving Farebrother enough time to consider this judgement. ‘And over Christmas, London will be packed with big spenders. Not much tail there for a captain without flying pay.’ Self-consciously he touched the top of his large bony head. There wasn’t much hair left there and he pushed it about to make the most of it. ‘I’ve got the use of a beautiful house in Cambridge over the holidays. See, Farebrother, I was determined to get out of this hellhole.’ He smiled. It was an engaging smile that revealed large perfect white teeth and emphasized his square jaw. ‘You stick with me, pal. I’ll fix us up with the most beautiful girls in England.’

‘What about your engagement?’ said Farebrother, more to be provocative than because he wanted to know.

‘The other night…what I said on the truck, you mean?’ He leaned forward and smiled at his mud-caked shoes. ‘Hell, that was never really serious. And like I say, London is too far to go for it.’ He drank some coffee and patted his lips dry with a paper towel—a delicate gesture inappropriate to a two-hundred-pound man built like a prizefighter. ‘I fall in love with these broads, I’m sentimental, that’s always been my trouble.’

‘I’m glad you told me,’ said Farebrother. ‘I would never have figured that out.’

Madigan grinned and drank more coffee. ‘Two of the most beautiful broads you ever saw…’ He paused before adding, ‘And fuck it, Farebrother, you can pick the one you want.’ He looked up as if expecting Farebrother to be overcome by this selfless offer. ‘One thing I’ll say, buddy, you’ll never be sorry you fixed me up with a decent place to sleep.’

Farebrother nodded, although he was already having doubts.

It took Captain Vincent Madigan the rest of the day to move into 3/11. He had water-soaked possessions stored all over the base as well as an electric record player and a small collection of opera recordings that he brought from his office. The musical equipment was placed on the floor to make room for a chest of drawers Madigan had obtained in exchange for cigarettes. The top of the chest was reserved for Madigan’s photographs. Apart from a picture of his mother, they were all of young women, framed in wood, leather, and even silver, and all inscribed with affirmations of unquenchable passion.

Farebrother re-examined Vince Madigan. He was a burly, amiable-looking man with thin hair, His nose was blunt and wide like his mouth. Although seldom seen wearing them, he needed spectacles to read the print on his record labels. Was this really the man who had won declarations of love from such beautiful young women? And yet who could doubt it, for Vince Madigan did not treat the photos like trophies. He never boasted of his exploits. On the contrary, it was his style to tell the world how badly the opposite sex treated his altruistic offers of love. By Vince’s account, he had always been unlucky in love.

‘I’m just not any good with women,’ he told Farebrother that evening while turning over a record, and totally disregarding the pounding noises coming from the unmusical occupants of the next room. ‘I tell them not to get serious…’ He shrugged at the perversity of human nature. ‘But they always get serious. Why not just be friendly, I say, but they want to get married. So I say okay, I want to get married, and wham—they change their mind and just want to be friends.’ He used a cloth to clean the record. ‘Sometimes I think I’ll never understand women. Sometimes I think these goddamned homos have got something, buddy.’

‘Is that right,’ said Farebrother, who hadn’t been listening. He’d been reading and rereading the same passage of the P-51 handling notes. Under it there was tucked a thick wad of regulations, technical amendments, orders and local restrictions. Reading it all through and committing it to memory would be a daunting task. ‘I’m not sure I’ll be through learning all this stuff by Christmas, Vince.’

‘You’re too darn conscientious, buddy. Who else in this Group, except maybe Colonel Dan, has waded through all that junk?’

‘I’m a new boy, Vince. They’ll be expecting me to screw it up.’ He riffled through the pages. ‘And to think I quit law school to get away from this kind of reading!’