По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

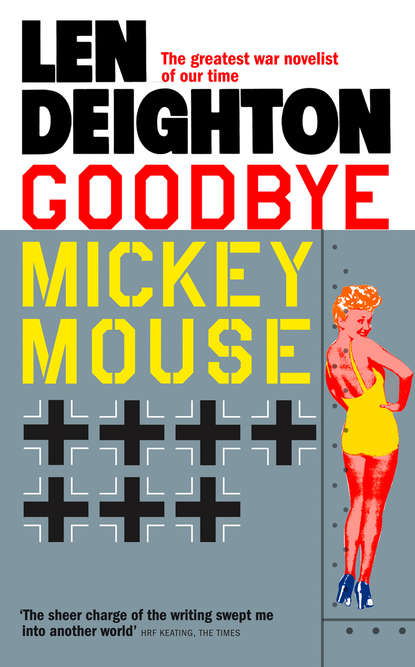

Goodbye Mickey Mouse

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Nothing like that,’ said Vera hastily. ‘Just friends. I feel sorry for those American boys, so far away from their homes and families.’ She picked up some photos and pretended to look at them. ‘I said I’d take a few friends along to their party at Christmas. You told me your parents will be away, so I wondered…’

‘I don’t think so, Vera.’ She’d been introduced to the American friend once, picking Vera up at the office, and wondered whether Vera had forgotten that or if she just enjoyed describing him again.

‘It’s Christmas, Miss Cooper,’ Vera coaxed. ‘I’m calling in to see them on my way home. Since it’s only round the corner I thought you might come with me—I’d rather not go on my own. They have wonderful coffee, and gorgeous chocolate—candy, they call it.’

‘Yes, so I’ve heard,’ said Victoria. It was a patronizing remark and Vera recognized it for what it was. Hurriedly, she gathered up some pay slips she was delivering to the cashier and turned to go. And since Victoria didn’t want to be rude to this genial woman, who would think it was because of her accent, or because she hadn’t been to college, she said, ‘I’ll go with you, Vera—I’d enjoy a break. But I mustn’t be too late home, I have to wash my hair.’

Vera gave a little shriek of delight, a sound borrowed no doubt from some Hollywood starlet. ‘Oh, I’m so pleased, Miss Cooper. It will be nice—he’ll have a friend with him…to help with the decorations and that,’ she added too quickly.

‘Am I what they call a “blind date”, Vera?’

Vera smiled guiltily but didn’t admit as much. ‘They’re ever so nice…real gentlemen, Miss Cooper.’

‘I hope you won’t go on calling me Miss Cooper all evening.’

‘See you at six o’clock, Victoria.’

Victoria could see why Vera was so impressed with the flat the Americans were using. It was both elegant and comfortable, furnished with good, but neglected, antique furniture, well-worn Persian carpets, and some nineteenth-century Dutch water-colours. The bookcases were empty except for the odd piece of porcelain. She guessed the place belonged to some tutor or fellow of the university, now gone off to war. The current tenancy of the Americans was unmistakable, however. There were pieces of sports equipment—golf clubs, tennis rackets, even a baseball glove—in various corners of the room and brightly coloured boxes of groceries, tinned food and cartons of cigarettes on the hall table.

She had arrived at Jesus Lane with some misgivings, half expecting to meet the predatory primitives her mother believed most American servicemen to be. She wouldn’t have been greatly surprised to find half a dozen hairy-chested men sitting round a card table in their underwear, smoking cheap cigars and playing poker for money. The reality couldn’t have been more different.

Captain Madigan and his younger friend were wearing their well-cut uniforms, sitting in the drawing room listening to Mozart. Both men were sprawled in the relaxed way only Americans seemed to adopt—legs stretched straight in front of them and heads sunk so low in the cushions that they had difficulty getting to their feet to greet their visitors.

Vincent Madigan acknowledged that they’d met before, remembering the time and place with such ease that she had little doubt that the invitation had originated with him. ‘I’m glad you dropped by,’ said Madigan, keeping to the pretence that Victoria was there only by chance. He stopped the music. ‘Let me introduce Captain James Farebrother.’ They nodded to each other. Madigan said, ‘Let me fix you ladies a drink. Martini, Vera? What about you, Miss Cooper?’ He leaned over to read the bottle labels. ‘Scotch, gin, port, something called oloroso—looks like, it’s been around some time—or a martini with Vera?’ His voice was unexpectedly low, contrived almost, and his accent strong enough for her to have some difficulty understanding him.

‘A martini. Thank you.’

James Farebrother offered them cigarettes and then asked permission to smoke. It was all so formal that Victoria almost started giggling. She caught Farebrother’s eye and made it an opportunity to smile. He grinned back.

Farebrother was a little taller than his friend but not so broad. His hair was cut very short in a style she’d seen only in Hollywood films. She guessed him to be about her own age—twenty-five. Both men were muscular and athletic, but Madigan’s strength was that of the boxing ring or football field, while Farebrother had the springy grace of a runner.

‘You must be the Mozart lover?’ she said.

‘No. Vince is the opera buff. I just beat time.’

His uniform was obviously made to order and she noticed that, unlike Vince Madigan’s, his tie was silk. Was it a gift from girlfriend or Mother, or a revelation of some secret vanity?

‘We’ll eat at a little Italian spot down the street,’ Madigan announced as he served the drinks. ‘They do a great veal scaloppine…as good as any I’ve had back home in Minneapolis.’

It was a bizarre recommendation and the temptation to laugh was almost uncontrollable. Madigan mistook Victoria’s amusement for indignation. Self-consciously he ran a hand over his bony skull to arrange his hair and backed away, almost spilling his drink as he blundered into the sofa. ‘Okay,’ he said. ‘Okay. I know what you British think about Mussolini and all that, and you’re right, Victoria.’

‘It’s not that,’ said Victoria. She glanced at Vera who was rummaging through the sports equipment. It was all right for her, she had short curly hair that always looked well but Victoria was appalled at the thought of going to a smart restaurant wearing the dowdy twin set she often wore at the office, and with her hair in a tangle.

‘Look at all this equipment,’ said Vera, waving a baseball-gloved hand. ‘Have you boys come over to fight a war, or just for the summer Olympics?’

‘We’ll go to the Blue Boar,’ said Madigan. ‘That would be much better.’

‘No…please,’ said Victoria. ‘Keep to your original plan, I’m sure it will be wonderful, but I really do have to get home.’

‘Please don’t go, Victoria,’ said Farebrother. ‘There’s plenty of food right here in the apartment. Why don’t we all just have some ham and eggs?’ His accent was softer and less pronounced than Madigan’s.

‘Oh, Victoria!’ said Vera. ‘You don’t really hate Italians, do you?’

‘Of course not,’ said Victoria. She watched her friend silently acting out tennis strokes with one of the new rackets she’d taken out of its cover. There was no mistaking the disappointment in her eyes—Vera loved restaurants; she’d often said so. ‘You and Vince go—don’t let me spoil your evening.’

‘We won’t be long,’ Vera promised softly. She became a different person in the company of men, not just in that way all women do, but animated and amusing. Victoria looked at her with new interest. She was older than Victoria, thirty or more, but there was no denying that she was the more attractive to most men. Her critics at the office, and there was no shortage of them, said Vera fed the egos of men, that she was doting and complaint, but Victoria knew that this wasn’t so; Vera was challenging and contentious, ready to mock the priorities and values of a masculine world. And certainly the war provided her with ample opportunities to do so.

Now she looked in a mirror to pat her curly yellow hair and pout long enough to apply lipstick. ‘We won’t be long,’ she repeated, still looking in the mirror. It was an appeal as much as a declaration—she wanted Vince Madigan all to herself across that restaurant table. She turned to exchange glances with Victoria and saw that the idea of an hour with James Farebrother was not unattractive to her; the alternative was going home to her parents’ chilly mansion in Royston Road.

‘I’ll cook something here,’ said Victoria. The promise was to Vera as well as to James Farebrother.

‘That’s great,’ he said. ‘Let me freshen that drink and I’ll show you the kitchen.’

The other two left with almost unseemly haste, and Victoria began to unpack the groceries the officers had bought from the commissary. It was a breathtaking sight for anyone who had spent four long years in wartime Britain. There were tins of ham and butter, tins of fruit and juice, biscuits, cigarettes and cream. There was even a dozen fresh eggs that Madigan had obtained from Hobday’s Farm near the airfield. ‘I’ve never seen so much wonderful food,’ said Victoria.

‘You sound like my sister opening her presents on Christmas morning,’ said Farebrother. He started the music again but lowered the volume.

‘The ration is down to one egg a week. And that tin of butter would be about four months’ ration.’ He smiled at her and she said, ‘I’m afraid we’ve all become obsessed with food. When the war’s over, perhaps we’ll regain a sense of proportion.’

‘But meanwhile we’ll feast on…’ He picked up some tins. ‘Ham and eggs and sweet corn and spaghetti in Bolognese sauce. Unless, of course, your embargo on things Italian is all-embracing, in which case we’ll ceremonially break Captain Madigan’s Rigoletto recordings.’

‘I don’t hate Italians…’

He put his hand on her arm and said, ‘Strictly between you and me, Victoria, the Italian cuisine in Minneapolis is terrible.’

She smiled. ‘I really don’t have any…’

‘I know. You simply don’t have a thing to wear and you think your hair is a mess.’

She put up a hand to her hair.

‘I’m sorry,’ he said. ‘I was kidding, your hair looks great.’

‘How did you guess why I didn’t want to go?’

‘Vicky, I’ve heard every possible excuse for being stood up.’

‘I find that difficult to believe.’ No one had ever called her Vicky before, but coming from this handsome American it sounded right. ‘Can you find a tin opener and cut up some ham?’

While she warmed the frying pan and sliced the bread, she watched him opening tins. He hurt his finger; clumsiness was a surprising shortcoming in such a man. ‘You’re a flyer?’

‘P-51s, Mustang fighter planes.’ He reached across her to get a knife from the drawer, and when his hand touched her bare arm, she shivered.

‘Escorting the bombers?’

‘You seem well informed.’ He used the knife to loosen the ham from the tin.

‘I work in a newspaper office.’