По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

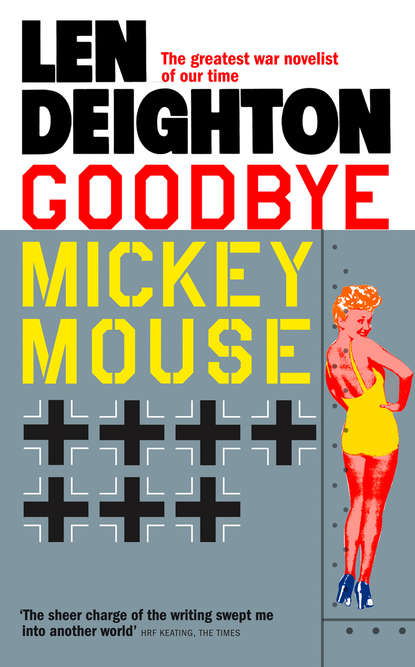

Goodbye Mickey Mouse

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘I didn’t know the British newspapers ever mentioned the American air forces.’ He looked up. ‘I’m sorry. I didn’t mean it to sound that way.’

‘Our papers do give most attention to the RAF—it’s only natural when so many readers have relatives who…’ She stopped.

‘Sure,’ he said. He shook the tin of ham violently until the meat slid out onto the plate.

‘How many raids have you been on?’

‘None,’ he said. ‘I just arrived. I guess I was a little premature in feeling neglected.’

‘The weather’s been bad. How many eggs may I use?’

‘Vince gets them by the truckload. Use them all if you like.’

‘Two each then.’ She cracked the eggs into the hot fat.

‘We need clear skies for daylight bombing. The RAF have magic gadgets that help them to see in the dark, but we only fly by day.’ He arranged the sliced ham on the plates.

‘But in daylight, with clear skies…doesn’t it make it easy for the Germans to shoot you down?’ She pretended to be fully involved in spooning fat over the frying eggs, but she knew he was looking at her.

‘That’s why they have us fighters.’

‘What about the anti-aircraft guns?’

‘I guess they’re still working on that problem,’ he said, and grinned. Abruptly the music from the next room came to an end. He reached out to her. ‘Victoria, you’re the only…’ He gently took her shoulders to embrace her. She gave him a quick kiss on the nose and ducked away.

‘I’ll turn Mozart over,’ she said. ‘You bring the plates to the table.’

They sat in the cramped kitchen to eat their meal. He poured two glasses of cold American beer and was amused to encourage Victoria to spread butter thickly on her crackers. He hardly touched his food. Victoria told him about her job and about her silver-tongued cousin who had recently become personal assistant to a Member of Parliament. He told her about his wonderful sister who was married to an alcoholic bar owner. She told him about the caraway-seed cakes with which her mother won annual prizes at the Women’s Institute competition. He told her about Amelia Earhart arriving at the Oakland airport in January 1935, solo from Honolulu, and how it made him determined to fly. At the age of fourteen he’d been permitted to take over the control wheel of a huge Ford tri-motor, owned in part by a close friend of his father.

There’s so much to say when you’re falling in love, and so much to listen to. They wanted to tell each other everything they had ever said, thought, or done. Their words were in collision. Victoria was overwhelmed by the magic of a bewildering people who dressed their humblest officers like generals, ate corn while leaving eggs and ham untouched, invented nylon stockings, and allowed their children to fly airliners.

‘Vince says every one of us has two faces; he keeps trying to prove that everything Mozart wrote is based on that idea.’

What had he been about to say, she wondered. Victoria, you are the only one for me. Victoria, you are the only girl I could ever marry. Victoria, you are the only girl in England who can’t fry four fresh eggs without breaking the yolks of two of them. She coveted the ones abandoned on his plate and wished she’d kept the unbroken ones for herself.

‘Not just the dressing-up they do in the operas, but the music that comments on each character.’

‘Are you both opera fans?’

‘If anyone could turn me off, it would be Vince.’

She smiled. ‘He’s intense, Vera told me that. Does everyone in Minneapolis have that sort of accent? At times it’s hard for me to understand just what he’s saying.’

‘Vince has moved around—New York, Memphis, New Orleans. He says that women like men with low, slow-speaking voices.’

She looked at the clock. Time had passed so quickly. ‘I must go. My parents are away and there’s so much I have to do before Christmas.’

‘Vince and Vera will have gone dancing.’

She stood up; she knew she had to leave before…and suppose Vera came back and found her here.

‘Don’t go, please,’ he said.

‘Yes, or it will spoil.’

‘What will spoil?’

‘This. Us.’

In the hallway she resisted his embrace until he pointed to the huge bunch of mistletoe tied to the overhead light. Then she kissed him and hung on as if he was the only life belt in a stormy sea. She was desperate that he wouldn’t ask when he might see her again, but just as she was on the point of humiliating herself with that question, he said, ‘I’ve got to see you again, Vicky. Soon.’

‘At the party.’

‘It’s not soon enough, but I guess it’ll have to do!’

Such mad infatuations don’t last for ever. The greater the madness, the shorter its duration—or so she told herself the following morning. Was she already a little more level-headed, and was this a measure of the limited enchantment of the handsome young American man who had come into her life?

‘It’s all right for you,’ said Vera trenchantly when Victoria made a harmless joke about the lateness of her return. ‘You’re young.’ She smoothed her dress over hips that a stodgy wartime diet had already made heavy. ‘I’m twenty-nine.’

Victoria said nothing. Vera pouted and said, ‘Thirty-two, if I’m to be perfectly honest with you.’ She fingered the gold chain she always wore round her neck and twisted it onto her finger. ‘My hubby is much older than me.’ She always referred to her absent husband as her ‘hubby’. It was as if she found the word ‘husband’ too formal and too binding. ‘Who knows when I’ll see him again, Victoria.’ She ignored the possibility that her husband might be killed. ‘It will be ages before they’re back from Burma. Do you know where Burma is, Victoria? It’s on the other side of the world. I looked it up on a map. What am I supposed to do? I might be forty by the time Reg gets back. I’ll be too old to have any fun.’

Victoria wondered how long she’d keep pretending that Vince Madigan was no more than a good friend. She sympathized. How could she tell poor wretched Vera to cloister herself for a husband who might never return? Yet she could never encourage her to betray him either. ‘I can’t advise you, Vera,’ she said.

‘It’s unbearable being on my own all the time,’ Vera said, almost apologetically. ‘That’s why I married my Reg in the first place—I was lonely.’ She gave a croaky little laugh. ‘That’s a good one, isn’t it?’ She twisted the gold chain until it was biting into her throat. ‘Little did I know I was going to be left all on my own within two years of getting hitched. I was in service when I was fifteen. With the Countess of Inversnade. I started as a kitchen help and ended as a ladies’ maid. You should have seen the shoes she had, Victoria. Dozens of pairs…and handbags from Paris. I was happy there.’

‘Then why did you leave?’

‘The government said domestics had to be in war jobs. Not that I know what I’m doing to win the war here, helping the cashier with the wages and getting tea for all those lazy reporters.’

‘Don’t be sad,’ Victoria said. ‘It’s Christmas Eve.’

Vera nodded and smiled, but didn’t look any happier. ‘You’re coming with me tonight, aren’t you?’

‘I have to go home to change first.’ She tried to keep her voice level—she didn’t want to reveal how eager she was to see Jamie again—but Vera’s shrewd eyes saw through her.

‘What are you wearing?’ Vera asked briskly. ‘A long dress?’

‘My mother’s yellow silk, I had it altered. The sister of that girl in the personnel office did it. She shortened it, made big floppy sleeves from what she’d taken off the bottom, and put a tie-belt on it.’

‘Vince must be sick of seeing me in that green dress,’ Vera said. ‘But I’ve got nothing else. He’s offered to buy me something, but I’ve got no ration coupons.’

‘You look wonderful in the green dress, Vera.’ It was true, she did.

‘Vince is trying to wangle me a parachute. A whole parachute! Vince says they’re pure silk, but even if they’re nylon it would be something!’ She picked up the outgoing mail from the tray as if suddenly remembering her work. ‘Victoria,’ she asked in a low voice as if the answer was really important to her. ‘Do you hate parties?’

‘I’m sure it will be lovely, Vera,’ she answered evasively, for the truth of it was that she did hate parties.

‘They’ll all be strangers. Vince has invited lots of men from the base and they’ll have girls with them. There’s no telling who might see me there…and start tongues wagging.’