По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

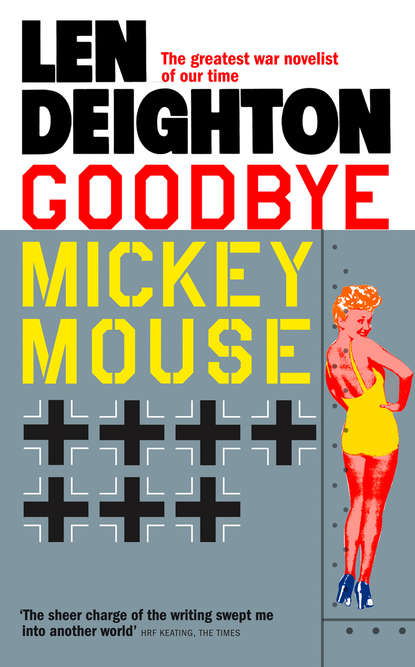

Goodbye Mickey Mouse

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘That’s about the way it is,’ said Gill without smiling.

‘Well, I hope Kruger and Lieutenant Morse won’t mind my borrowing their ship.’

‘Lieutenant Morse won’t mind—Mickey Mouse they call him—and he’s mighty rough with airplanes. He says planes are like women, they’ve got to be beaten regularly, he says.’ Gill still didn’t smile.

Farebrother offered his cigarettes, but Gill shook his head. ‘Kruger, he won’t mind too much,’ said Gill. ‘It don’t do an airplane any good to be standing around in this kind of weather unused.’ He took off his hat and looked at it carefully. ‘Colonel Dan now, that’s something else again. Last pilot who flew across the field…I mean a couple of hundred feet clear of the roofs, not your kind of daisy-cutting—Colonel Dan roasted him. He was up before the commanding general—got an official reprimand and was fined three hundred bucks. Then the Colonel sent him back to the US of A.’

‘Thanks for telling me, Sergeant.’

‘If Colonel Dan gets mad, he gets mad real quick, and you’ll find out real quick too.’ He wiped the rain from his face. ‘If you ain’t heard from him by the time you’ve unpacked, you ain’t going to hear.’

Farebrother nodded and drank his coffee.

Sergeant Gill looked Farebrother up and down before deciding to give him his opinion. ‘I don’t reckon you’ll hear a thing, sir. See, we’re real short of pilots right now, and I don’t think Colonel Dan’s gonna be sending any pilot anywhere else. Especially an officer who’s got such a good feel for a ship that needs a change of spark plugs.’ He looked at Farebrother and gave a small grin.

‘I sure hope you’re right, Sergeant Gill,’ said Farebrother. And in fact he was.

3 Staff Sergeant Harold E. Boyer (#ulink_4f3b60f4-a6c4-5efc-b2f1-a98c8facd2ba)

Captain Farebrother’s flying demonstration that day passed into legend. Some said that the men on duty at Steeple Thaxted exaggerated their descriptions of the flight in order to score over those who were on pass, but such attempts to belittle Farebrother’s aerobaties could only be made by those who hadn’t been present. And Farebrother’s critics were confuted by the fact that Staff Sergeant Harry Boyer said it was the greatest display of flying he’d ever seen. ‘Jesus! No plane ever made me hit the dirt before that. Not even out in the Islands before the war when some of the officers were cutting up in front of their girls.’

Harry Boyer was, by common consent, the most experienced airman on the base. He’d strapped into their rickety biplanes nervous young lieutenants who were now wearing stars in the Pentagon. And no matter what aircraft type was mentioned, Harry Boyer had painted it, sewn its fabric, and probably hitched a ride in it.

Harry Boyer not only told of ‘Farebrother’s buzz job’, as it became known, he gave a realistic impression of it that required both hands and considerable sound effects. The end of the show came when Boyer gave his fruity impression of Tex Gill drawling, ‘Everything okay, sir?’ and then, in Farebrother’s prim New England accent, ‘You’d better change the plugs, Sergeant.’

So popular was Boyer’s re-enactment of the flight that when he performed his party piece at the 1969 reunion of the 220th Fighter Group Association, a dozen men crowding round him missed the exotic dancer.

Staff Sergeant Boyer’s reputation as a mimic was, however, nothing compared to his renown as the organizer of crap games. Men came from the Bomb Group at Narrowbridge to gamble on Boyer’s dice, and on several occasions officers turned up from the 91st BG at Bassing-bourn. It was his crap game that got Boyer into trouble with the Exec.

Although Boyer and the Exec had carried on a long, bitter and byzantine struggle, the sergeant’s activities had never been seriously curtailed. But whenever it leaked out that some really big all-night game with four-figure stakes had taken place, Boyer frequently found himself mysteriously assigned to extra duties. So it was that Staff Sergeant Boyer had found himself in charge of the detail painting the control tower that day.

At the end of Farebrother’s hair-raising beat-up, Boyer looked over to the Operations Building, expecting the Exec and Colonel Dan to come rushing out of the building breathing fire. But they did not come. Nothing happened at all except that Tex Gill finally rode over to the tower on his bicycle, laying it on the ground rather than against the newly painted wall of the tower. ‘And how did you like that, Tex?’ asked Boyer. ‘On those slow rolls he was touching the grass with one wing tip while the other was in the overcast. Did you see it?’

‘He’s clipped the radio wires off the top of the tower,’ said Tex Gill.

Determined not to rise to one of Tex Gill’s gags, Boyer pretended not to have heard properly. ‘He’s what?’

‘He clipped the radio wires on that low pass.’ Tex Gill was a deadpan poker player who’d frequently taken money from the otherwise indomitable Boyer, so, still suspecting a joke, the staff sergeant would not look up at the antenna.

Tex Gill held out his fist and opened his hand to reveal a ceramic insulator and a short piece of wire attached to it. ‘Just got it off his tail.’

‘Does Colonel Dan know?’

‘Even the guy who just flew those fancy doodads don’t know. I figured that you and me could rig a new antenna right now, while your boys are finishing up the paint job.’

‘That’s strictly against regs, Tex. There’d have to be paperwork and so on.’

‘That captain just arrived,’ said Tex Gill. ‘I was with him on the truck from London last night. We don’t want to get him in bad with the Colonel even before he’s unpacked.’

Staff Sergeant Boyer rubbed his chin. Tex Gill could be a devious devil. Maybe he figured there was a good chance that the new pilot would take Kibitzer, in which case Tex would be his crew chief. ‘Well, I’m not sure, Tex.’

‘If someone reports that broken antenna, the Exec is going to come over here, Harry. And he’ll see your paintwork is only finished on the side that faces his office, and he’ll see that some clumsy lummox has spilled two four-gallon cans of white on the apron…’

Boyer looked at the flecks of spilled paint on his boots and at the insulator that Tex Gill was holding. ‘You got any white paint over there at your dispersal?’

‘I’d be able to fix you up, Harry.’ Tex Gill threw the insulator to Boyer, who caught it and winked his agreement. By the end of work that day the tower was painted and the antenna was back in position. Captain Farebrother never found out about it and neither did the Exec or Colonel Dan.

4 Lieutenant Z. M. Morse (#ulink_8fba0a0d-7297-5f18-94d1-9431007eb8a2)

Lieutenant Morse returned from four days in London with a thick head and a thin wallet. He desperately wanted to sleep, but he had to endure two young pilots sitting on his bed, drinking coffee and eating his candy ration and telling him all about the fantastic new flyer who’d been assigned to the squadron. ‘What the fuck do I care what he can do with a P-51?’ asked Morse. ‘I was happy enough with my P-47, and if I’d been Colonel Dan I wouldn’t have been so damned keen to re-equip us with these babies. Jesus! They stall without warning, and now they tell us the guns jam if you fire them in a tight turn.’ Morse was sprawled on his bed, his shirt rumpled and tie loose. He grabbed his pillow and punched it hard before shoving it behind his head. A large black mongrel dog asleep in the wicker armchair opened its eyes and yawned.

Morse, who’d grown so used to being called Mickey Mouse, or MM, that he’d painted the cartoon on his plane, was a small untidy twenty-four-year-old from Arizona. His dark complexion made him seem permanently suntanned even in an English winter, and his longish shiny hair, long sideburns and thin, carefully trimmed moustache caused him to be mistaken sometimes for a South American. MM was always delighted to act the role and would occasionally try his own unsteady version of the rumba on a Saturday night, given a few extra drinks and a suitable partner.

‘They say it was terrific,’ said Rube Wein, MM’s wingman. ‘They say it was the greatest show they ever saw.’

‘In your ship,’ added Earl Koenige, who usually flew as MM’s number three. ‘I sure would have liked to see it.’

‘How old are you jerks?’ said MM. ‘Come on, level with me. Did you ever get out of high school?’

‘I’m ninety-one going on ninety-two,’ said Rube Wein, Princeton University graduate in mathematics. There was only a few months’ difference in age between the three of them, but it was a well-established vanity of MM’s that he looked more mature than the others. This concern had led him to grow his moustache—which still had a long way to go before looking properly bushy.

‘I see you guys sitting there, Hershey bars stuck in your mouths, and I can’t help thinking maybe you should be riding kiddie cars, not flying fighter planes to a place where angry grown-up Krauts are trying to put lead into your tails.’

‘So who gave the new kid the keys to your car, Pop?’ said Rube Wein. This broody scholar knew how to kid MM and was prepared to taunt him in a way that Earl Koenige wouldn’t dare to.

‘Right!’ said MM angrily. ‘Why didn’t he take Cinderella or Bebop? Or better, Kibitzer, which is always making trouble. Why does he have to go popping rivets in my ship? That son-of-a-bitch Kruger is paid to look after that machine. He should never have let this new guy fly her.’

‘Why didn’t he use Tucker’s plane?’ said Rube Wein, who strongly disliked his Squadron Commander. ‘Why didn’t he take that fancy painted-up Jouster and maybe wreck it?’

‘Colonel Dan’s orders,’ explained Earl Koenige, a straw-haired farmer’s son who’d studied agriculture at Fort Valley, Georgia. ‘Colonel Dan told this guy to go out and fly a familiarization hop. Of course it’s only scuttlebutt, but they say Farebrother asked was it okay to fly it inverted.’ Meeting the blank-eyed disbelieving stares of the others, he added, ‘Maybe it’s not true but that’s what they say. The Group Exec is furious—he wanted Farebrother court-martialled.’

‘There should be a regulation about taking other people’s airplanes,’ said MM. ‘And inverted flying is strictly for screwballs.’

Earl Koenige tossed back his fair hair and said, ‘Colonel Dan said the new pilot hadn’t been in the base long enough to make himself familiar with local regulations and conditions. And the Colonel said that the especially bad weather that day created a situation in which low flying in the vicinity of the base was a necessary measure for any pilot new to the field about to attempt a landing in poor visibility.’ Earl laughed. ‘Or put it another way, Colonel Dan needs every pilot he can get his hands on.’ Having related this story, Koenige looked at MM. He always looked at his Flight Commander for approval of everything he did.

MM nodded his blessing and put another stick of gum into his mouth. It was his habit of chewing gum and smoking at the same time that made him so easy to impersonate, for he’d roll the cigarette from one side of his mouth to the other with a swing of the jaw. Anyone who wanted an easy laugh at the bar had only to do the same thing while flicking an imaginary comb back through his hair to create a recognizable caricature of MM. ‘Sure! Great!’ MM shouted, clapping his hands as if summoning hens out of the grain store. ‘And beautifully told. Now cut and print. Get out of here, will you! I’m not feeling so hot.’

Rube Wein leaned over MM where he was sprawled out on the bed and said, ‘It’s chow time, MM. How would you like me to bring you back some of those greasy sausages and those real soggy french fries that only the Limeys can make?’

‘Scram!’ shouted MM, but the effort made his head ache.

‘Rumour is that this new guy is going to get Kibitzer, and that means he’ll be flying as your number four, MM,’ said Rube Wein.

MM threw a shoe at him, but he was out of the door.

Winston, MM’s dog, looked up to see if the thrown shoe was intended for him to bring back, decided it wasn’t, growled unconvincingly, and closed his eyes again.

Not long afterwards there was a polite tap at the door, and without waiting for a response, a tall thin captain put his head into the room. ‘Lieutenant Morse?’