По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

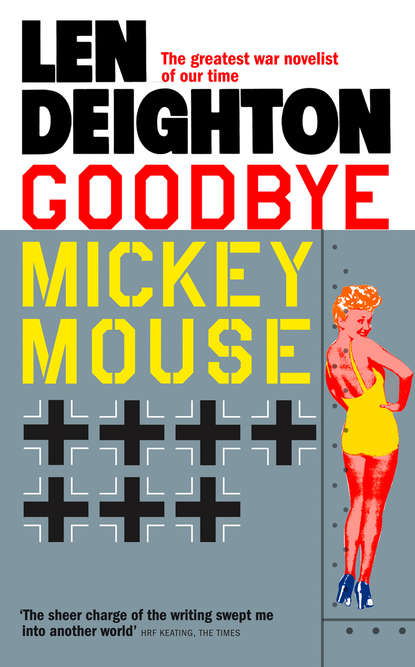

Goodbye Mickey Mouse

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

16 Lieutenant Colonel Druce ‘Duke’ Scroll (#litres_trial_promo)

17 Victoria Cooper (#litres_trial_promo)

18 Lieutenant Stefan ‘Fix’ Madjicka (#litres_trial_promo)

19 Henry Scrimshaw (#litres_trial_promo)

20 Vera Hardcastle (#litres_trial_promo)

21 Major Spurrier Tucker Jr (#litres_trial_promo)

22 Captain Vincent H. Madigan (#litres_trial_promo)

23 Dr Bernard Cooper (#litres_trial_promo)

24 Lieutenant Colonel Druce ‘Duke’ Scroll (#litres_trial_promo)

25 Brigadier General Alexander J. Bohnen (#litres_trial_promo)

26 Captain James A. Farebrother (#litres_trial_promo)

27 Colonel Daniel A. Badger (#litres_trial_promo)

28 Major Spurrier Tucker Jr (#litres_trial_promo)

29 Lieutenant Colonel Druce ‘Duke’ Scroll (#litres_trial_promo)

30 Captain Vincent H. Madigan (#litres_trial_promo)

31 Victoria Cooper (#litres_trial_promo)

32 Captain Milton B. Goldman (#litres_trial_promo)

33 Brigadier General Alexander J. Bohnen (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About The Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Other Books By (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Introduction (#ulink_82e03025-1fb3-5463-87ae-43701d141924)

‘Never before; never since and never again,’ said a US Eighth Army Air Force veteran when I was researching this book.

He was describing one particular moment in the final months of the war. RAF Bomber Command was operating in the daytime, and flying in loose formations of squadrons instead of in the ‘stream’ it had used previously in night bombing. The RAF heavy bombers were returning across the English Channel at the same time as seemingly endless squadrons of American air force bombers were setting out in tight formations. ‘The sun glinted on them,’ said the American flyer. ‘There must have been a thousand of those RAF heavies. I was in the turret; we were leading the low squadron. All around me and behind and ahead there were over a thousand of our ships. Everywhere I looked, the sky was filled with planes.’

Perhaps he was exaggerating but other flyers remarked upon such awesome sights. The missions of ‘Big Week’ frequently comprised 800 aircraft and this short period of intense air activity was one of the most decisive battles of the war. Certainly there were times when two thousand British and American four-engined bombers shared the sky, and the men who saw these vast, futuristic fleets of aircraft never forgot. Neither did the people—British and German—who with pride and apprehension watched them from the ground.

Goodbye Mickey Mouse was rooted in a failure. I had abandoned a half-completed story about the air fighting in Vietnam when the fighting there ended. To prepare for that Vietnam book I had spent several weeks on a US Air Force base. They gave me a chair in the ready room, a physical exam with jabs, a flight suit with all the paraphernalia and a bed; and let me join the day-to-day life of the aircrew on the base. I ate with the flyers, drank with them, went to their barbecues and flew backseat in the F-4 Phantom. We dropped bombs, flew in formation and did air-to-air refueling. My assigned pilot was Captain Johnny Jumper, a young Vietnam veteran who not only became a life-long friend but also became a General and eventually the US Air Force Chief of Staff.

Writers hate waste. My vivid experience with the US Air Force nagged me and eventually became a starting point for reconstructing the 1944 US Army Air Force base in England where Goodbye Mickey Mouse takes place. Malcolm Bates, a resolute amateur historian in Porlock, persuaded me to look again at the war fought by the US air forces in Europe. Malcolm had read my book, Bomber, and wanted me to write about the American side of the air war. He sent me long letters, carefully chosen books and useful pictures. His enthusiasm fired me. I had visited American bases in England in 1944 and the structure I envisaged for the book came into my mind easily. I had always been intrigued by the degree of self-sufficiency that military bases achieved. Metal-working shops and pharmacies, libraries and prison cells, dental surgeries and chapels, ice cream parlours, movie theatres and tailor shops. There was no need to go anywhere for anything. American bases were more all-inclusive than the RAF ones I had visited, for there was a prevailing order that the British economy should not be taxed with American demands for food and supplies.

When, in the postwar world, the air force veterans of the 91st Bombardment Group returned to their old base at Bassingbourn to revive memories and exchange yarns, I was infiltrated into the party by one of the organizers: Wing Commander ‘Beau’ Carr. I spent an inspiring week with these remarkable men. ‘That was my bed,’ one elderly ex-navigator told his wife as he slapped its blanket in a barrack room now occupied by young soldiers. He looked around the room, turning his head slowly: ‘And this was my home.’

To emphasize this ‘little town’ concept I decided to allot one character to each chapter so the story was told through the eyes of technical specialists, clerks and tradesmen as well as the flyers. I had tried this before in a very simple way. In Only When I Larf chapters were provided for the first person narrative of three different people. One of them was a woman. Such a construction requires unrelenting attention to dialogue and detail. Every sentence, in fact every word, must be scrutinized carefully to establish, distinguish and maintain the integrity of the separate characters. And for that book the accounts varied according to the memory and motives of each person.

Editors can sometimes be important to the process of writing a book. It was a very fine American editor, Georgie Remer, who gently advised me to drop this ‘one first-person character per chapter’ idea. Georgie usually edited top level political and military memoirs and she had taken me, a fiction writer, on as an experiment. From my point of view her help was wonderful and she taught me the first principles of editing. A dozen or more American regional speech patterns and accents would be a big problem even for a well-travelled American writer, Georgie said. She would not advise anyone to try such a device. I was convinced that it could be done but Georgie was an extraordinary woman and her warning was apt; it would add months of extra work and pitfalls galore. So Georgie and I compromised. I tell the story from different viewpoints but I would look over the shoulder of each participant rather than relate the episode in their voice.

When I wrote Bomber, a book about an RAF strategic bombing raid in 1943, I devoted a large part of the story to the life and day-to-day activities of the Germans. Goodbye Mickey Mouse was a fundamentally different project. For this book I wanted to examine the social life of the ‘Little America’ that was the air base, and the mixed reactions of the English civilians living nearby. Because I have found that conversation is the finest basis of research I spent a long time with veterans in America. Despite the lengthy research I was determined to keep the story line clear and well structured.

A simple plot demands complex characters. I have never been lucky enough to have my characters fortuitously emerge from the keyboard, speak to me from blank pages or drift into my dreams. Like some latter-day Count Frankenstein, I have to fashion my characters to fit the needs of my story but not fit readily to each other. To give you a crude idea of what I mean: Victoria is a part of an old, over-confident, expiring world, while being young female and vulnerable. Jamie is strong and assured but feels uncertain about the foreign world in which he finds himself. Mickey Morse is a wild card; an alarming, unpredictable representative of the sort of social revolution that war brings. Equally important to me was the father and son relationship; the General and his son Jamie are separated by the love they have for each other. It is a generational gap that neither man can bridge or reconcile.

Goodbye Mickey Mouse is a love story. Almost every fiction book I have written is to some extent a love story; I suppose I must be some sort of closet romantic. This story is a somewhat prosaic tale. It depicts desperate wartime romances and the cruel anguish they bring to all concerned.

Len Deighton, 2009

Prologue, 1982 (#ulink_3f1e215a-5e4c-571f-858e-15dd246a2ecb)

Three buses moved with almost funereal slowness through the narrow winding country lanes. Overhead the sky was dark with rain clouds. The passengers stared out at the meadows and the pretty villages, defaced by advertising, TV antennas and traffic signs, and at the orchards and streams drained of colour by the long months of winter.

The buses did not stop until they reached one large ugly field disfigured by the rusting metal skeletons of old Quonset huts and brick remains. Slashed across this huge field, like some monstrous sign of plague, there was a concrete X. Here and there strenuous attempts had been made to remove this disfigurement, but only tiny pieces had been nibbled from the great cross.

Cautiously the passengers disembarked into the chilly winds that scour the flat East Anglian farmlands. Huddled against the weather, palms outstretched to detect rain in the air, zipped and buttoned to the neck, they formed into small silent groups and wandered dejectedly through the ruined buildings.

They were Americans. They wore brightly coloured windcheaters and tartan hats, they carried cameras and tote bags, none of them was equipped with the heavy sweaters and thick overcoats that England’s climate demands so early in the year. They were white-haired and they were balding, they were florid and they were ashen, they were fat and they were frail, but, apart from a few young relatives, they were all in that advanced stage of life that we optimistically call middle age.

The nervous clowning and the determined laughs of the men demonstrated the tense anxiety behind their movements. Wives watched knowingly as their men frantically searched in the workspace of the echoing old hangar, paced out the shape of a long-vanished barrack hut, peered into dark corners or scratched upon dirt-encrusted windows to find nothing but ancient farm machinery. They’d waited a long time; they’d paid hard-earned money; they’d come a long way to find the man they sought. Sometimes it became necessary to consult an old photo for identification purposes, at other times they listened for half-remembered voices. But as the group grew quieter and, in deference to the cold, returned to the warm buses, it became evident that none of them had discovered the man they all so clearly remembered.

One couple separated from the others. Holding hands like young lovers, they followed a potholed tarmac road that, like a huge ring, surrounded the field, touching the extremities of the crossed runways. The man and woman talked as they took a shortcut along a farm track. They unhooked themselves from blackberry bushes, stepped over cow dung, and picked a wood violet to be pressed flat into a diary and kept as a souvenir. They spoke about the weather and the crops and the colours of the countryside. They spoke about anything except what was uppermost in their minds.

‘Look at the cherry blossom,’ said Victoria, who had not lost her English accent despite thirty years in San Francisco. They both stopped at the orchard gate which once marked the end of Hobday’s Farm and the edge of the airfield.

‘Why did Jamie stay in the bus?’ said the man. He rattled the farm gate. ‘Isn’t he interested in seeing where his father flew from in the war?’

Victoria hugged him. ‘You’re his father,’ she said. ‘You tell me.’

1 Colonel Alexander J. Bohnen (#ulink_5f4421f5-bcb8-5f41-87ef-350b2c9adf10)

Colonel Alexander J. Bohnen’s large office overlooked Grosvenor Square. The furniture was a curious collection of oddments: two lumpy armchairs from the American Embassy’s storeroom smelled of mothballs, his desk and a slab-sided table, loaded with box files, bore the markings of Britain’s Ministry of Works. The antique carpet and a Sheraton china cabinet were air-raid salvage that Bohnen had bought cheaply in a London saleroom. Only the folding chairs, six of them stacked tidily behind the door, were American in origin. But it was December 1943 and London was very much at war.

The clouds were dark and low over the bare trees of the square. The soft silvery grey barrage balloon wore a crown of white and there were patches of fresh snow on the grass. But elsewhere the snowflakes died as they reached the ground and the hut that sheltered the balloon’s operating crew was shiny and wet. Smoke from the stove twisted with every gust of wind, and chased the snow flurries. For once there was no sound of aircraft. Little chance of a German air raid today; nature was providing its own barrage.

Colonel Bohnen, US Army Air Force, was a tall man in his middle forties. His uniform was well cut and he had buffered his appearance against the onset of age by a daily routine of exercise, aided by expensive dentists, hairdressers, masseurs and tailors. Now, with the same waistline he’d had at college, and nearly as much wavy hair that was only slightly greying, he could have been mistaken for a professional athlete.