По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

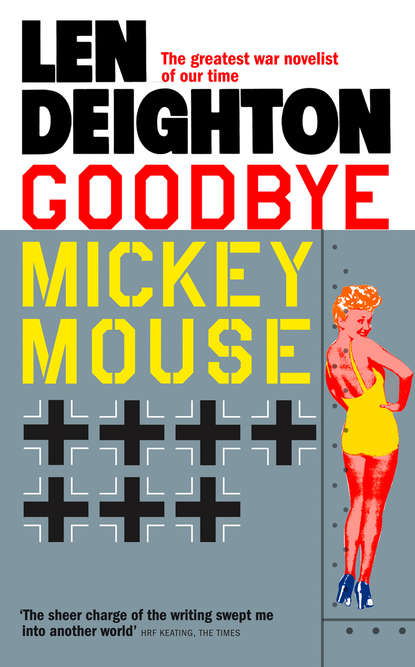

Goodbye Mickey Mouse

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

His visitor was an elderly American civilian, a sober-suited white-haired man with rimless spectacles. He was older than Bohnen, a friend and business associate. Twenty years before, he had been part owner of a small airline and Bohnen a trained engineer with contacts in the banking world. It was a relationship that permitted him to treat Bohnen with the same sardonic amusement with which he’d greeted the overconfident youngster who’d pushed past his secretary two decades earlier. ‘I’m surprised you settled for colonel’s rank, Alex. I thought you’d hold out for a star when they asked you to put on your uniform.’

Bohnen knew it was a joke but he answered earnestly. ‘It was a question of what I could contribute. The rank means nothing at all. I would have been content with sergeant’s stripes.’

‘So all that business about your expecting a general’s star at any moment is just moonshine, huh?’

Bohnen swung round sharply. His visitor held his stare a moment before winking conspiratorially. ‘You’d be surprised what you hear in the Embassy, Alex, if you wear rubber-soled shoes.’

‘Anyone I know there last night?’

The old man smiled. Bohnen was still the bright-eyed young genius he’d known so long ago: ambitious, passionate, witty, daring, but climbing, always climbing. ‘Just State Department career men, Alex. Not the kind of people you’d give dinner to.’

Bohnen wondered how much he’d heard about the excellent dinner parties he hosted here in London. The guests were carefully selected, and the hostess was a titled lady whose husband was serving with the Royal Navy. Her name must not be linked with his. ‘Work keeps me so busy I’ve scarcely got time for a social life,’ said Bohnen.

The man smiled and said, ‘Don’t take the Army too seriously, Alex. Don’t start reading up on the campaigns of Napoleon or translating Thucydides. Or practising rifle drill in your office, the way you used to practise golf to humiliate me.’

‘We’ve got too many businessmen walking around in khaki just because it’s a fashionable colour,’ said Bohnen. ‘We’re fighting a war. Any man who joins the service should be prepared to give everything he’s got to it. I mean that seriously.’

‘I believe you do.’ There was a steel lining to Bohnen’s charm, and he pitied any of Bohnen’s military subordinates who hesitated about giving up ‘everything’. ‘Well, I’m sure your Jamie will be green with envy when he hears you got to Europe ahead of him. Or is he here too?’

‘Jamie’s in California. Flying instructors do a vitally important job. Maybe he doesn’t like it, but that’s what I mean about the Army—we all have to do things we don’t like.’

‘His mother thinks you arranged that instructor’s job.’

Bohnen turned to glance out of the window again. The old man knew him well enough to recognize that he was avoiding the question. ‘I don’t have that kind of authority,’ said Bohnen vaguely.

‘Don’t get me wrong—Mollie blesses you for it. They both do, Mollie and Bill. Bill Farebrother treats your boy as if he was his own, do you know that, Alex? He loves your boy.’

‘They would have liked a son, I guess,’ said Bohnen.

‘Yes, well, don’t be mulish, Alex. They don’t have a son, and they both dote on your Jamie. You should be pleased that it worked out that way.’

Bohnen nodded. There was virtually no one else who would have dared to speak so frankly about Bohnen’s first wife and the man she’d married, but they’d been good friends through thick and thin. And there was no malice in the old man’s frankness. ‘You’re right. Bill Farebrother has always played straight. I guess we were all pleased that Jamie was assigned to instruction.’

‘I suspect you had a hand in Jamie’s assignment,’ said the man. ‘And I suspect that Jamie is every bit as clever as his father when it comes to getting his own way. Don’t imagine he won’t find a way to get into the war.’

‘Has Jamie written to you?’ Bohnen was alert now and ready to be jealous of this man’s friendship with his son. ‘This is important to me. If the boy is being assigned to combat duty I have a right to know about it.’

‘I only know that he visited his mother on leave. He sold his car and cleared out his room. She was worried that he might have been sent overseas.’

The old man watched Bohnen as he bit his lower lip and then moved his mouth in exactly the same way he’d seen young Jamie do when working out a sum or learning to take the controls of a tri-motor plane. Bohnen looked at his wristwatch while he calculated what he could do to check up on his son’s movements. ‘I’ll get on to that,’ he said, and pursed his lips in frustration.

‘You can’t keep him in cotton wool for the rest of his life, Alex. Jamie’s a grown man.’

Bohnen got to his feet and sighed. ‘You don’t understand me, you only think you do. I don’t give myself any easy breaks, and if you were under my command I’d make sure no one ever accused me of going soft on old buddies. If Jamie’s looking to his old man for any kind of special treatment he can think again. Sure, I put in a word that helped assign him to Advanced Flying training. I know Jamie; he needed more time before flying combat. But that’s a while back, he’s ready now. If he comes here, he’ll take his chances along with any other young officer.’

Bohnen’s visitor stood up and took his coat from the hook on the door. ‘It’s not a sin for a man to favour his son, Alex.’

‘But it is a court-martial offence,’ said Bohnen. ‘And I don’t quarrel with that.’

‘You’ve fallen in love with the military, Alex, the same way you’ve fallen in love with every project you’ve ever taken on.’

‘It’s the way I am,’ admitted Bohnen, helping the old man into his overcoat. ‘It’s why I’m able to get things rolling.’

‘But in wartime the Army has a million lovers; it becomes a whore. I don’t want to see you betrayed, Alex.’

Bohnen smiled. ‘What was it Shelley said: “War is the statesman’s game, the priest’s delight, the lawyer’s jest, the hired assassin’s trade.” Is that what you have in mind?’

The visitor reached for his roll-brim hat. ‘I envy you your memory even more than your knowledge of the classics, Alex. But I was thinking of something Oscar Wilde said about the fascination of war being due to people thinking it wicked. He said war would only cease being popular when we realized how vulgar it was.’

‘Oscar Wilde?’ said Bohnen. ‘And when was he a reliable authority on the subject of war?’

‘I’ll tell you next week, Alex.’

‘The Savoy, lunch Friday. I’ll look forward to it.’

2 Captain James A. Farebrother (#ulink_aa903b7a-0260-5fcd-917f-7f8df470d810)

‘You’re the luckiest guy in the world, I’ve always told you that, haven’t I?’

‘So what happened to the man who was going to be the richest airline pilot in America?’ replied Captain James Farebrother, made uncomfortable by the note of envy in his friend’s voice.

Captain Charles Stigg pulled back the canvas flap to see out of the truck. London’s streets were dark and wet with rain, but even in the small hours there were people about. There were soldiers and sailors in fancy foreign uniforms. There was a jeep with British military police wearing red-topped caps, and some civil defence personnel wearing steel helmets. There must have been another air-raid warning.

‘Nearly there now,’ said Farebrother, more to himself than to his friend. Separation from Charlie would be a bad wrench. They’d been together since they were aviation cadets learning to fly on old Stearmans, and it was easy to understand why they’d become such good friends. Both were calm, confident young men with easy smiles and quiet voices. More than one member of a selection board had said they were not aggressive enough for the ritual slaughter now taking place daily in the thin blue skies above Germany.

‘Why didn’t I bring my long underwear?’ said Charlie Stigg, letting the flap close against the chilly air.

‘It’s nearly Christmas,’ said Farebrother.

‘I guess almost anything will be better than teaching Cadet Jenkins to land an AT-6.’

‘Almost anything will be safer,’ said Farebrother. ‘Even Norwich on a Saturday night.’

‘You know why I stopped going to the Saturday-night dances?’ said Charlie Stigg. ‘I couldn’t face another of those girls telling me I looked too young to be an instructor.’

‘They didn’t mean anything by that.’

‘They thought we were ducking out of the war—they figured we volunteered to be flying instructors.’

‘The kind of girl I met at the dances didn’t even know there was a war on,’ said Farebrother.

‘Norwich,’ said Stigg. ‘So that’s how you pronounce it; I guess I’ve been saying it wrong. Yeah, good. Come over there and see me, Jamie, it sure will cheer me up.’ The truck stopped and they heard the driver hammering on his door to signal that this was Stigg’s destination, the Red Cross Club.

‘Good luck, Charlie.’

‘Look after yourself, Jamie,’ said Charlie Stigg. He threw his bag out onto the ground and climbed down. ‘And a merry Christmas.’

It wasn’t fair. Charlie Stigg had been hardworking and conscientious enough to master the complications of flying multi-engined aircraft, so when they finally let him go to war they turned down his application for fighters and sent him to a Bomb Group. Farebrother deliberately flunked his conversion to twins and got the assignment that Charlie so desperately wanted. It wasn’t fair, war isn’t fair, life isn’t fair.