По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

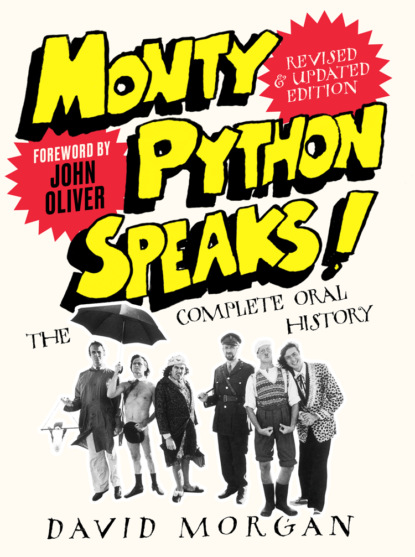

Monty Python Speaks! Revised and Updated Edition: The Complete Oral History

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

So they said, ‘Absolutely no way – we want you with us for the rest of the series.’ So that’s what happened. I really owe it to the fellas that I became the Monty Python girl because they put their foot down.

By now Ian MacNaughton was doing the directing. Ian wanted to have different ladies in each episode and he wanted to be responsible for the casting, so the fellas put their foot down and said, ‘Uh-uh.’ They came to the agreement that if Ian wanted someone to just literally stand there and say nothing and just look pretty, fine, he could cast that, but if there was any sort of acting involved, the fellas wanted me. And that was the agreement they came to and that was how I came to be in the series.

How was working with the Pythons different from working on other comedy programmes?

CLEVELAND: Working with Spike Milligan was almost traumatic – an amazing experience but exhausting because you never knew what this man was going to do next. But the other people I worked with were all fairly sane – I mean, very funny but it was all fairly sane stuff, you knew what was going on; there wasn’t quite such a lunacy with those. With the Pythons I really didn’t know what to expect. It’s just a wonderful combination of looniness and great wit and intelligence and foresight. When I first joined them, I didn’t honestly quite know what to make of it to begin with. I remember the first two or three days of rehearsal thinking, ‘I don’t know if this is going to take off,’ because they were sort of all over the place. It was fairly manic.

We didn’t actually do a lot of rehearsal. If anything, it was under-rehearsed to keep it fresh and fun. Lots of people say to me, ‘How much of that was improvised?’ Because it came over so fresh, they felt a lot of it was being improvised. And I say, ‘Well, none of it; none of it was improvised. It was all scripted, everything.’

Carol Cleveland, steadfast straight woman to the group, in Monty Python Live at the Hollywood Bowl.

There wasn’t a lot that went on in the first few days of rehearsal; because they had written it themselves, they knew exactly what they wanted, so they knew just what was going to happen. Once they knew exactly what they were doing, in order to keep it fresh, we’d just stop rehearsing and the rest of the time was mucking about. Once we’d done our little bit of rehearsal we’d go, ‘Right, that’s good now, we don’t want to sort of louse it up,’ we’d do something like play football. So all of the furniture would be moved aside and we set up a couple of goals at each end and we’d have a football match. I was always a goalie! And we had a great time at rehearsals mucking about, I have to say, much to the amusement of passers-by. When we were in the BBC Centre rehearsal rooms (which are great, big, vast rooms), all the doors have little peek-through windows, and it was wonderful – as people pass by, you’d see them come back and take a double take, and not know what to make of it. They thought we were rehearsing a football sketch that went on day after day after day.

What allowed you to work so well with the group as their foil?

CLEVELAND: Well, certainly I was very prepared to have a go. There was very little they could ask me to do that I would ever say ‘no’ to. I was willing and able, and I’d throw myself into it with great gusto. I guess there’s a fair amount of lunacy in me, there must have been to get into things the way I did, and I think that was very appealing to them. I could do the sort of ‘glamour dollie bird’ bit and put that across very well but at the same time send myself up on that. I was quite happy to go over the top with anything and I think that was the other thing that they liked. And obviously they felt I had quite a good comedy flair and I looked good as well, which was a combination they wanted.

It still irritates me that I meet Python fans and their recollections seem to be of me without any clothes on! I never took my clothes off in Python, not entirely. There was a lot of me in underwear and showgirl outfits and bathing suits and lingerie, but never without any clothes. The nearest I came to that was when we were filming ‘Scott of the Sahara’. In that I’m being chased by a man-eating roll-top desk, having my clothes ripped off bit by bit by cacti. I’m running towards the camera on each occasion, and on the last one my bra comes off and I’m still meant to be running towards the camera and I was feeling a little bit shy about all sorts of things, and certainly the fact that we were filming on a crowded beach and there were masses of people milling about, so I did feel a little bit inhibited about that. I wasn’t happy about running towards the camera with my bra coming off so in fact they did change it. The last shot is of me topless running away with my back to the camera as I pass John sitting at his desk facing the camera. But that was the only time I think I ever resisted. And the funny thing is that I suppose if they asked me to do it now, I’d say, ‘Yeah, great, I’ll do it!’ But it’s too late now, they won’t ask me!

Was there difficulty in that there were Python wives and girlfriends who also appeared in the shows but not as frequently as you?

CLEVELAND: I suppose if I had been a wife or a girlfriend I wouldn’t have got the job! Connie Cleese appeared occasionally, and Eric’s then-wife Lynn Ashley appeared, but only occasionally. Neither of them would have actually wanted to be involved, I think; it was only because they were wives that they were brought in.

I don’t think I would have got the job if I had been heavily involved [with one of them]. And I remember very early on Terry Gilliam did ask me out on a date – when I think how things might have turned out if I’d said ‘yes’! I said ‘no’ for two reasons: first of all because I actually had a boyfriend who was an extremely jealous Italian, but I think I would have said no anyway because business and pleasure don’t mix. As it turns out Terry dated a make-up girl on the show, Maggie, and they’re now married and very happy.

What were your impressions of the Pythons?

CLEVELAND: Individually they were all as they were collectively: brilliant, clever, fun, very nice men. The only one I never really felt close to was Eric. All the others treated me like one of the boys, and I never quite felt that with Eric. Eric always seemed a little distant, rather aloof. He in my opinion was the most serious of the lot, and the most businesslike. He was the one that always had his head together as far as the financial side of Python was concerned. If anyone started getting a little bit too wacky he would be the one to say, ‘Well, yeah, but this one is going to cost such-and-such.’

Terry Jones: very excitable, being a Welshman very emotional, quite fiery at times. I was never present at the writing sessions or the business meetings but I’m told that he was the one that had been known to throw things. And he, along with Terry Gilliam, were the two looniest of the lot, who would cause the most havoc and confusion during the rehearsal period.

Terry Gilliam, also very excitable, very visual, very loud! And you never quite knew what was going on in his head, until you actually saw the animations – and when you saw the animations you really got quite worried about what was going on there!

Graham always did everything to excess, everything he did: obviously his drinking, and the way he flaunted his homosexuality, which wasn’t the done thing in the early Seventies certainly, and caused a certain amount of embarrassment at the time. Personally I felt quite embarrassed by some of his behaviour. I don’t know quite how to describe Graham; I sort of describe his behaviour rather than his personality. He was a lovely man. I think because of his drinking and his homosexuality, everyone felt they needed to take care of Graham a little.

John: the most logical, definitely moody, like all comic geniuses a complex man but he was the only one who really changed during the course of Python. When he was going through his questioning period with his psychoanalysis, he was actually at times quite unpleasant to be around. He was unfriendly and difficult – certainly that’s what I noticed. Fortunately, by the time we were doing Life of Brian he was back to being his fun self.

And as for Michael, well, Michael has never changed. He’s the one that’s never changed at all, and he remains the same charming, shy, sweet, helpful person that he is, and he is of course the only one who’s actually quite shy, and that’s very appealing, which is why all the women adore Michael. He was always the ladies’ favourite.

IF THEY CAN’T SEE YOU, THEY CAN’T GET YOU

MACNAUGHTON: This was a very strange thing because when I’d done four or five Monty Python shows which had not yet gone out, I was called to the head of entertainment, who said to me, ‘I don’t think we’ll be renewing your contract.’ I had a year’s contract. So I said, ‘Oh, really? Why not?’ He said, ‘Well, this Q5 show of yours was a bit of a cult success, but only on BBC2. [!] And who really wants to see the Monty Pythons?’ They were ready to drop me. It wasn’t that they were going to drop the Pythons; they just didn’t think that the way we were doing it – which meant me as producer and director – was what was wanted. Fortunately I think their public became of a different mind – the Pythons went out and became a cult success.

Promotional item in the Radio Times:

MONTY PYTHON’S FLYING CIRCUS

is the new late programme on Sunday night.

It’s designed ‘to subdue the violence in us all’.

The first Python show, broadcast on October 5, 1969, demonstrated quite clearly that the group was after something quite uncategorizable. It presented a surreal mix of violence (Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart hosts a programme depicting famous deaths); television parodies (‘We find that nine out of ten British housewives can’t tell the difference between Whizzo butter and a dead crab.’ ‘It’s true, we can’t!’); occasions where all propriety is ripped to shreds (an interviewer proceeds to address his guest as ‘sugar plum’ and ‘angel drawers’); some intellectually tainted comic bits (Picasso paints while riding a bicycle, followed by Kandinsky, Mondrian, Chagall, Miró, Dufy, Jackson Pollock, ‘… and Bernard Buffet making a break on the outside’); and a loopy premise allowing for both some slapstick and social commentary (the tale of the World’s Funniest Joke, appropriated by the army as a weapon against the Nazis, who fail miserably at developing a counter-joke of their own). Running throughout the programme were gags and animations about pigs.

In the weeks that followed, the programme became more fragmented, more surreal, more violent. Sheep nesting in trees gave way to a man playing the ‘Mouse Organ’ (namely, some rodents trained to squeak at a certain musical pitch accompanied by a pair of heavy mallets), to a cartoon of a pram that ingests the doting women who lean too closely. Kitchen-sink melodramas were turned on their heads, as when a young coal miner returns home to his playwright father, who rants about his son’s values (‘LABOURER!’). A scandal-mongering documentary examines men who choose to live as mice (‘And when did you first notice these, shall we say, tendencies?’). And a confectioner is investigated for fraud in labeling his latest product, Crunchy Frog (‘If we took the bones out it wouldn’t be crunchy, would it?’).

How was the series sold originally by the BBC?

TOOK: Well, it’s this ‘new wacky series, these wacky kids, these bright new Cambridge graduates and Oxford lads who delighted us for years with their merry antics, now together at last in a brand-new series’. I suppose that’s what they did. That’s what they do about everything else!

GILLIAM: The BBC I think were constantly uncomfortable with us. They didn’t know quite what we were, and I think they were slightly embarrassed by it, and yet it was too successful, it was making all this noise out there. When they took us off after the fourth show (this was the first series), we were off for a couple of weeks, I think there was a serious attempt to ditch it at that point. But there was too much noise being made by us. The most wonderful thing was everybody tuning in when Python was supposed to run and it was the International Horse of the Year Show; in the middle of it, they were doing their routines to music, it was Sousa’s ‘Liberty Bell’ – our theme music. It was like Python was even there, you couldn’t keep it down!

But in the beginning they would put us out at all these different times, and change it, but somehow the word got out and they kept us on.

TOOK: The BBC split up into different areas, and the option was to take the show or not to take the show, and half the regions didn’t take the first series. So if you lived in London you’d get it; if you went down to Southampton on the south coast you wouldn’t be able to see it because they put on Herring Fishing in the North Sea or something. It was very irritating that the regions had that kind of autonomy; there was nothing you could do. But the word started to go around that this was very good and very new, and something they ought to have. So one after another came back into the fold, and by the time the second series was done, the complete network had it.

CLEESE: I had a friend who was trying to watch the series, and he sat down in his hotel room in Newcastle and switched it on and there was this hysterical start to Monty Python about this guy wandering around being terribly boring about all the ancient monuments around Newcastle. And he watched it falling about, and said it’s real nerve to do this, it’s really terrific and what a great start to the show. And about twenty minutes in he realized it was the regional off-time.

The nicest thing anybody ever said about Python was that they could never watch the news after it. You get in a certain frame of mind and then almost anything’s funny!

HE WANTS TO SIT DOWN AND HE WANTS TO BE ENTERTAINED

How was the public’s response to your work different from what you’d experienced on your previous series?

PALIN: I suppose the difference was that, partly because of its programming and the time it went out, Python clearly was seen as very much for an adult audience, which is very interesting because nowadays the spirit of Python burns on in ten-year-olds, twelve-year-olds, thirteen-year-olds. So many children love Python. But at the time it was seen as an adult show. I’d never really been involved in an ‘adult’ show, kind of X-rated comedy show, and this seemed to be the image of it.

And also we became sort of the intellectuals’ darling for a bit, written up in The Observer, things like that, which was again quite different from anything I’d done before. The word ‘cult’ was quite soon applied to Python, though we weren’t quite sure what a ‘cult show’ is. It applies to something that is the property of only a very few select people. I’d never been interested in doing that before. Frost Report was a very popular show; Do Not Adjust Your Set was aimed at a popular audience. But Python seemed to fit into this niche of daring, irreverent, therefore only accessible to those of a certain sort of intellectual status, and that lasted for a long time.

So much in television depends on when programmes go out. The BBC labelled the programme – without meaning to – by the time we put it out. We were put out so late at night and people who had to work early next morning couldn’t see it; there wasn’t videos, you couldn’t tape them and run them the next morning if they were put out late at night. Insomniacs and intellectuals were the only people up!

MACNAUGHTON: You do know about Spike Milligan’s remark on the radio once when somebody asked him about the success of the Pythons? ‘Oh,’ he said, ‘my nephews are doing very well, aren’t they?’ Which is a very reasonable thing, because they loved Milligan.

Python would not have been what it was had it not been for

The Goon Show or the Q series.

MACNAUGHTON: Precisely. But would The Goon Show have been what it was were it not for the Marx Brothers? And then would the Marx Brothers have been the way they were were it not for burlesque, and would burlesque have been the way it was were it not for music halls? And so it’s got a wonderful progression, I think.

The trouble is, since Python I haven’t seen anything come up yet that takes its place. And I’m very pleased, because quite honestly I don’t think you can. I guess that’s one of the big pluses for Python, in that nobody can really copy their style – it doesn’t work. I mean, Morecombe and Wise can be copied. But how do you copy [these] guys? I think it would be very difficult to do it again.

CLEESE: My experience is that critics recognize what is slightly original, but very frequently miss what is very original! And if you look back at the reviews of Monty Python’s Flying Circus, they were really not particularly noticeable – nothing remarkable about the reviews for quite a long time. I suspect you would probably get to show nine or ten of the first series before anybody was really writing that something remarkable was happening. A few people got it right away. But critics on the whole did something that they do when they’re insecure: they describe what the show was like without really committing themselves to a value judgment.

GILLIAM: We’d rather be making films that people are passionate about than, ‘Oh, that’s a nice film.’ And Python’s always managed to do that; people are passionate about Python. I think that’s where we’ve always been good. That’s probably the area we should stay in. It’s like comic books; comic book artists and people who deal in comic book all feel like outsiders, they’re never given respect. There’s an amazing skill involved in making a good comic book. The artwork in comic books is brilliant, some of the writing is brilliant – comic books is a really great art form, but it’s not [considered] art. Not literature. It’s this bastard thing hanging out there. And they complain, [but] I keep saying, ‘No, you’re lucky that you haven’t been accepted – keep being angry and outside and doing stuff.’ Because if you become a Keith Haring or Basquiat or any of these people who get drawn into the Establishment, they die, they just freeze up. What’s Keith Haring? His stuff is nice and it’s sweet and it’s cute, it’s all right, but I don’t think when they look back a hundred years from now they’re going to say, ‘He nailed it.’ Except maybe they will: that’s how infantile and silly things had got, that in fact he captured the essence of the whole thing doing just nice, sweet stick figures and nice colours. I don’t dislike his stuff at all, I think it’s nice, but I don’t think it’s Wow!!

I think certainly with comedy, comics, and all that – comics/comedy, we’re stuck with sounding very similar! – that’s outside, and it should stay outside.

MACNAUGHTON: They were quite surprised by the positive reaction to the Gumbys, these daft people with the handkerchiefs tied on their heads. When they walked into the studio one time, what happens but the whole front row of the audience had handkerchiefs tied around their heads! Gumby just had to appear and there was a roar of laughter.

GILLIAM: I’m the luckiest one because I’m the least known, the least recognized. And it’s nice to be recognized occasionally. I get enough, somebody saying ‘Hi,’ just to assuage my fading ego: ‘That’ll keep me going for a month or two.’