По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

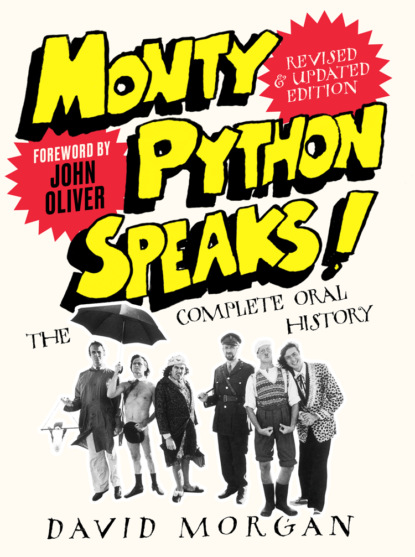

Monty Python Speaks! Revised and Updated Edition: The Complete Oral History

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

MACNAUGHTON: We did the usual BBC style of five or six days’ rehearsal. On the sixth day there would be a technical run-through for all the lighting, etc., and then we were one day in the studio. And of course all the stuff we had filmed we showed to the audience in the studio as we did each episode.

Cleese and Idle in rehearsal, c. 1971.

From the beginning I had no problem working with them because they’re extremely disciplined as actors, as comic actors.

We honestly had a very good working relationship. I have never from the beginning had one problem with any of them. I felt myself to be a part of the team anyway.

I can remember one time John looking at me after a sketch had been done and saying, ‘Why aren’t you laughing?’ And I said, ‘Well, there’s something not quite right with this sketch.’ He said, ‘You hear that, gentlemen? Let’s do it again.’ They did it again, and he said, ‘No, I think we’ll find a new one,’ and did a new one the next day.

I can’t remember any explosions. Come the second series there was one moment and that was quite fun: we were making the film ‘The Bishop’, and I’d set up the opening shot with a lower-level camera. The bishop’s car raced up to the camera, stopped, out jumped all the mafia bishops, etc., and ran up to the church. Now Terry Jones said to me, ‘No, no, you must do this in a high angle.’ And I said, ‘No, I think the low angle’s better for this opening,’ knowing what had gone before. ‘No, no, no!’ We had a bit of a row, and we walked off together, Terry kicking stones right and left. And I said, ‘Look, Terry, just leave it for a moment – anyway, I haven’t got a cherry picker with me and can’t get the big high angle that you’re looking for.’ We came back and did it. We then went on another location in Norwich I think it was, and where we saw the rushes from the previous week, up came the rushes for ‘The Bishop’ – and this is what’s so nice about the whole group: Terry Jones turned around in the hotel’s dining room where we were watching the rushes, held his thumb up to me, and said, ‘You were right, it worked perfectly.’ And that is I think the biggest row we ever had, and it’s not a very big one, you must admit.

JONES: In studio, we tried to do it sequentially as much as we could. It was a bit stop-and-starty sometimes, but we tried as much as we could to rush through the costume changes. We only had an hour and a half recording time anyway, so you had thirty-five minutes of material to record. We very often did it as a live show with just a few hitches, try and keep the momentum going to keep the audience entertained. We didn’t want to stop the show because it meant the audience going off the boil a bit.

MACNAUGHTON: We had a studio audience of 320; that was a BBC policy, to have a studio audience. And you know, never had we laid a laugh from a laugh track on Python. It was a kind of policy, because we thought if the audience don’t really like it, they won’t laugh anyway, and there’s nothing worse than listening to shows that have laugh tracks on and the audience is roaring with laughter at something you’ve found totally unfunny yourself.

JONES: For me, when we came to the editing the audience was always the great key – we always had that laughter to go by so you knew whether something was working or not. And if something didn’t get a laugh, then we cut it. A lot of the time we were actually having to take laughs out because it was holding up the shows.

I remember one show that didn’t seem to work in the studio, and that was ‘The Cycling Tour’. Everybody came out very disappointed, all the audience and our friends going, ‘Eh, that wasn’t very good, didn’t really work, that.’ And of course the trouble with that was that it wasn’t shot sequentially, or even when it was shot sequentially it was very stop-and-starty. Like all the stuff in the hospital, the casualty ward, was very quick cuts – a sign falling off, a trolley collapsing, a window falling on somebody’s hand – that all had to be shot separately, so they didn’t seem very funny at the time. But when you cut them in very fast, that made it seem quite funny.

MACNAUGHTON: At the beginning they all wanted to come to the editing, and I said, ‘That’s no use, we can’t have five guys standing around me standing around the editor.’ So in the end only Terry used to come to the editing. We’d sit together and we’d say, ‘Yes, I think cut there,’ and ‘No, I think it should be cut later,’ and ‘No, I’m sorry, I think it’s quicker’ – the usual thing. There were honestly no problems.

GILLIAM: Terry tended to be the one to be in the editing room, sitting looking over Ian’s shoulder, and keeping an eye on things. I popped in occasionally, John, different people. Terry was almost always there.

Ian dealt with the BBC, basically; we didn’t have to. That’s the great thing about the BBC, it’s not like American television; once they said ‘Go’, they basically left. It was a real, incredibly laissez-faire operation. That was the strength of the place, because it just allowed the talent to get on to do what it did. And in the end the talent ended up producing more good material than all these meetings are producing now. I don’t think the batting average is any better now than it was then, it’s actually worse, and they all end up sitting around talking things to death. It was very simple: you’ve got this series, we want seven shows now and six later and you do it, that’s it.

We had freedom like nobody gets now, basically. And the only time we started getting some involvement from them was later on, I think it was probably the third series, because as we’d become successful they felt that they had to interfere in some way, to be involved in this thing.

WHY DON’T YOU MOVE INTO MORE CONVENTIONAL AREAS?

PALIN: I think there was always a conscious desire to do something which was ahead of or tested the audience’s taste, or tested the limits of what we can or cannot say. I think it’s probably strongest in John and Graham’s writing; they enjoyed being able to shock, whereas Terry and I enjoyed surprise more than shock. For us it was more putting together odd and surreal images in a certain way which would not offend but really jolt, surprise, and amaze. John and Graham took some pleasure in writing something which shocked an audience. I think this came from within, but John never seemed to be totally happy or centred – there was always something which John was having to cope with. And that desire to shock I think came from the way Graham was, too. Graham was a genuine outsider, a very strait-laced man who was homosexual and an alcoholic at that time and therefore found himself constantly in conflict with people, and so he would fight back. And the two of them would put together things like the ‘Undertaker Sketch’ purely because they knew it was outrageous, and yet they did it in a way none of the other Pythons would have done, so it was quite refreshing. When we first heard that we thought, ‘Well, we just can’t do it.’ But then you think about it: this is a really good, refreshing view of death, talking about it that way. In that particular case I think yes, there was a desire to shock an audience by talking about something that was not talked about.

Terry and I were not quite so interested in taboos.

Was it because, having been journeymen scriptwriters for hire, your previous experience did not allow for taboo material?

If you had written taboo material for others, you wouldn’t have got hired again.

PALIN: No, I don’t think that’s it, I think it just wasn’t in our nature to write deliberately shocking material; we couldn’t make it very funny. We could surprise, we could amaze. It was personal, it was nothing to do with our writing; in fact, quite the opposite: the writing that we had to do in the Sixties made us relish Python and the freedom Python had. We utterly supported John and Graham and what they were writing, and for us it was all part of the freedom of Python: to do stuff we wouldn’t have been able to do as journeymen writers. Great, someone writes a sketch about undertakers; it seemed shocking to start with it, you look at it and say, ‘Okay, let’s give this a go.’ And that was part of the exhilaration of doing Python. But no, I don’t think Terry and myself were particularly good about getting laughs [from] very abrasive material. There might have been instances, I can’t remember, [but] we were more about human behaviour, moralizing.

SHERLOCK: Cleese as he’s got older has become more conservative, but when they first started out Python was really quite left-wing; it was considered by some to be commie and subversive.

IDLE: Always we tried to épater les bourgeois.

Once when filming, a British middle-class lady came up and said, ‘Oh, Monty Python; I absolutely hate you lot.’ And we felt quite proud and happy. Nowadays I miss people who hate us; we have sadly become nice, safe, and acceptable now, which shows how clever an Establishment really is, opening up to make room inside itself.

FRANKLY I DON’T FULLY UNDERSTAND IT MYSELF, THE KIDS SEEM TO LIKE IT

MACNAUGHTON: Now Terry Gilliam was meanwhile working on the animation links for all the shows; sometimes Terry’s film would arrive on the day we were recording that certain episode. No one had seen it beforehand, but everybody trusted everybody else. Which was a very good thing.

GILLIAM: [In story meetings] I always had the most difficulty because I could never explain what I was doing; whenever I did, there would be these blank faces. I was in maybe the best position because I had the most freedom. The others had to submit all their material to the group and get rejected or included or changed; mine, because I couldn’t explain it, and because we were always revising at the last moment, was pretty much never touched.

What was the actual process like for you?

GILLIAM: Sometimes I had an assistant working on Python; Terry’s sister-in-law Katie Hepburn assisted me for a while. Basically it was me on my own, with books.

I’d always start: there were the scripts, they go from there to there, and I just sort of had an idea, an image to start with. A lot of times I had a lot of ideas, a lot of things I wanted to get into the shows; I just had to stick them in between and find connecting tissues to get from there to there. So I would use these little storyboard sketches, then I would start looking for the artwork; whether it was stuff I had drawn myself or pictures that I got from books, I’d start getting the elements together.

And in the end the room is all these flats full of artwork. It became like a scenic dock for a studio: I’d have the ground, and I’d have different skies, and I could build a background very quickly after a certain point, and then I just started, totally a magpie approach, things that I liked I use and chop up. If it was photos I needed, I’d send the books in to the photographic place and blow them up to the sizes I want and start cutting them out; usually they wouldn’t be complete so I’d have to draw or airbrush part of it.

Conrad Poohs and His Dancing Teeth.

So I’d have all this artwork and I’d go to the BBC’s rostrum camera, set it up, and just start pushing the stuff around. You’d find at three or four in the morning the papers arranging themselves after a while! The stuff kind of made itself. You pile all these things there and they start forming patterns, a thing lands on top of that; ooh, that’s an idea. It was really free, because even though I had storyboarded and set out with a very specific look or an idea I was after, if I couldn’t find it I’d grab something that was just as good or it would be a little bit different than I expected but I could make it work, and it would flow in that direction.

And I would always shoot long; a lot of the work was done in the editing room afterwards, because I never knew quite [how long] somebody would talk. I would just wiggle the mouth up and down – leave it open for twelve frames, close it for ten – and then later I would chop frames out to try and get it vaguely to [match] whatever was being said. And then for voices I either do them myself, or I’d run and get the guys in the corridor, or in rehearsal. I just stand there with a tape recorder and say, ‘John, say this, say that; okay, good, thank you. Terry, say that …’ And the BBC had a great sound effects library which is all on discs, [but] a lot of times I’d just sit at home, a blanket over my head, with a tape recorder, making noises with kitchen utensils, and just record this shit. And then I’d get down to the editing room and we’d start sticking it all together. I was working seven days a week, it was just crazed. There’d be at least one all-nighter in there.

Cannibalism, Gilliam-style.

All the underground press were convinced I was an acidhead, they thought all of us were on drugs but me in particular, and we weren’t – it’s all natural stuff!

And it’s not like a Disney cartoon where everything’s planned and drawn; it’s using things around me, and just incorporating and letting it grow organically.

I was producing this stuff in two weeks [for each show]. Some of the [location] filming I wouldn’t get to because I was desperately trying to get ahead. I’d have to keep up with the shows, so by the end of the series it was always a mad rush. It was weird.

When you sail in a race, you just go out on the ocean, and you come around a buoy and all the boats are there, and before you get to the next marker everybody disperses and goes a different way; suddenly you’re alone. And then you come to the next marker buoy and Oh! Everybody converges. And it was kind of like that in doing the shows; we’d have the meetings, I’d be there as part of the group, then I’d go off into my world, and we’d only get together the days the shows were being recorded. So they were always together, they were always at rehearsals. My problem was there was one side of me that wanted to be a performer as well, but I really didn’t think I was in their class, so I’d just turn up on the days we were recording and take that little part there, put on a costume, do something silly there, just to keep myself both from being bored and feeling more a part of the thing. Because they were having all the fun, and I felt I was doing all the work!

In story meetings, would you ever bring a fully devised sketch to be animated, such as ‘The House Hunters’ [in which two hunters armed with ‘condemned’ posters track a wild building]?

GILLIAM: I wouldn’t have brought it in as a sketch – I would bring it as an idea. ‘I want to do this whole thing about house hunters, it’s a literal thing.’ And again they didn’t know quite where to put those things because they couldn’t imagine them; that was part of the problem. If I wanted to do that little story, in a sense it was up to me to find the right spot to slide that in. I’m trying to remember whether I would actually say, ‘I’ve got a thing that’s probably going to run about three minutes.’ I honestly can’t remember whether I was ever that specific. Because we’d try to work out a thirty-minute show, so I’m sure I must have been saying ‘a big chunk’. ‘I’ve got a big thing to do here,’ something specific!

A typical magpie approach.

Terry always loved what I was doing, and Mike. It’s so weird because Terry and Mike are much more visually oriented than the others, but it may just have been my inability to explain things. John I think was constantly bemused by my stuff, he was so – ‘intimidated’ is probably too strong a word, but he didn’t know how to criticize it, so he never criticized it except for this one thing where he could actually go, ‘Well, that’s blasphemous,’ or ‘That’s offensive.’ [See page 146.]

That was the bad side of it: I felt at times I wasn’t getting any of the benefit of the criticisms of the group. We all had to be self-criticizing, saying, ‘That doesn’t work,’ ‘That’s not good enough for the shows.’ But a lot of times I never got a sense that they knew whether [what I did] was good or bad, whether it worked or didn’t work, because it was another language that they don’t understand. John didn’t understand the language.

In the English language there’s no word for ‘visual illiteracy’. You have ‘illiterate’, but visual? There’s no term for it; it’s the idea that visual things are not a language. There is a visual language, and yet people who invent words don’t invent that word. I want to use ‘ivvisualites’, people who are visually illiterate.

It’s a thing that intrigues me, the information you get from images; they’re saying things and they’re telling these stories and they don’t necessarily have to be words. Being down with these kids at the Royal College’s Animation Department, some of the stuff they’re doing is just wonderful, but if you sit down and go, ‘Tell me the story,’ they can’t do it. A splotch of stuff here, a funny little noise happens there, what’s that? And yet it’s fantastic – at least it is for me. I look at some of their stuff and I’m not sure that John Cleese would find it funny, I don’t think he would know what to say about it. Sounds like I’m picking on John, but he was the most visually illiterate; I think it’s that. But I wish the others would have been able to come up and say, ‘Terry, that’s pretty weird.’ They didn’t!

Was any animation ever rejected out of hand?

GILLIAM: There was this thing that Ian MacNaughton just completely fucked up because he didn’t understand it, and Terry hadn’t been in the editing room that day. It was a strange abstract thing – it’s really hard to describe! I mean, it was like trees growing and reaching barriers in space you can’t see, and then they go around and did all sorts of really strange and interesting things. And I don’t know what he was thinking when he did it, he just didn’t get what it was and he cut it. That was a big mistake, [but] that wasn’t like somebody censoring.

BUT IT’S MY ONLY LINE!

CAROL CLEVELAND, ACTRESS: I had been doing a fair amount of work at the BBC, doing what I call – I think this is my own definition – a ‘glamour stooge’, working alongside people like Ronnie Corbett, Ronnie Barker, and Spike Milligan.

When the Pythons were starting, I hadn’t met any of the fellas at all, though I knew a little of their work. They’d written five episodes of the original thirteen, and they were looking for a female. Somebody at the Beeb suggested my name and John Howard Davies saw me and cast me. I hadn’t realized at that stage that my contract wouldn’t go further than four episodes; I only discovered that when my agent got in touch with the Beeb. By this stage we’d got going and I got on extremely well with the guys, they thought I fitted in beautifully. I think they were more than happy with my contribution, and when Michael came up to me when we were doing episode three and said, ‘Oh, we have got something great for you coming up,’ – because already they felt that they weren’t quite utilizing my talents enough and they wanted to give me something more to do than just giggle and smile, as I did in the ‘Marriage Guidance Counsellor’ sketch – I said, ‘Well, it sounds great but I’m not in episode six.’ And he said, ‘What? What?’ And he went over and spoke to the others, John came over and said, ‘What’s this?’