По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

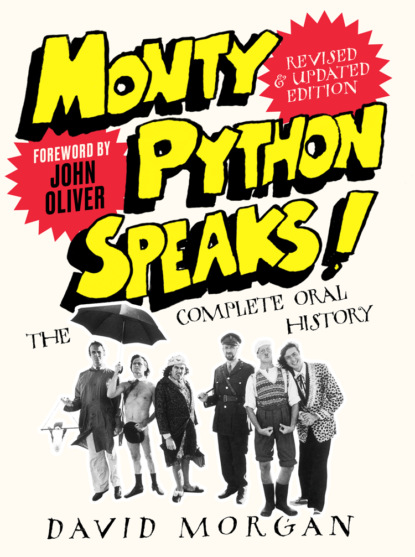

Monty Python Speaks! Revised and Updated Edition: The Complete Oral History

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

PALIN: No, no, no. I used to read our stuff, and John used to read the stuff that he and Graham wrote. I can’t really give you a reason for that other than Terry was happy that that’s the way it was, and Graham was quite happy that John should read his. I think we were perhaps wary of selling this as a complete sketch. In a way by just one person reading it would be like reading notes for a sketch, it wouldn’t be taken too seriously – you know, this wasn’t a full performance you were being judged on, this was just a way of gauging whether it was funny or not. You could also read it much more quickly, it was much easier to get the essence of it quite quickly.

CLEESE: The great joy of the group was that we made each other laugh immoderately. We had dinner together quite recently, all of us except Eric, and we all said afterwards we don’t really laugh with anyone else the way we laugh together – we really make each other laugh more than anyone else makes us laugh. And so the great joy of the meetings, one of the totally positive things that kept us ticking over and happy for a long time and probably helped us when things weren’t so easy, was the fact that we laughed so much.

But if you read something out at a meeting and people became hysterical with laughter, whatever was read out next would always be anticlimactic. So there was a certain amount of very careful stage managing going on during meetings, because I would come in with the material that Graham and I had written, and I would be very aware that approval would vary according to certain extrinsic factors. The usual psychological factors were at work, such as don’t read your best stuff out first. Also, the first couple of things read out were unlikely to produce enormous laughter.

While I was reading material out, I was often adjusting the order because you could sometimes sense the energy of the group start to slump after a couple of hours; and if Mike and Terry just read out something screamingly funny, I would not try and read out something terribly funny after that; I would read out something that was sort of interesting and clever and witty.

JONES: We just read out material, it wasn’t performing it. Quite often there might be two or three characters, so it’d be difficult to actually perform it. Mike’s the better reader of the two of us, in the same way that John was the better reader. And I always felt if I read something it wouldn’t do it justice – partly because of my reading, and partly I think I didn’t quite know what kind of mood John would be in – he might sort of take against something if he felt it was partly mine!

PALIN: And also it was the sensitive area of casting. If you cast it already, even if it’s just the two writers, you in a way staked a claim on those characters, which was difficult for the others to take. We would not make suggestions [on casting]; it was done really quite democratically. We’d actually rather people say, ‘I’d like to do that’ or whatever, or then we’d say, ‘This is a sort of Eric-type character.’ Sometimes it was clear, it didn’t need discussion. Sometimes very often the people who’d read that sketch had read a character so well that there was no point in putting it out to tender, as it were. But then casting would come slightly later because you’d have to assemble the show first. Once the show’s assembled, then the casting could really begin because we wanted it to be fairly equal; one didn’t want one person to dominate, and everyone wanted to perform – everyone was dead keen to get up there and do the sketches. We were aware without ever saying it absolutely, as a sort of rule, that there should be a balance in casting. When we had all the sketches together, we would say, ‘Actually you can’t put those three together because they’re all three John characters; so let’s put this sketch in show eight, and then bring an Eric sketch from show eight to this one. So you have John, Eric, then the thing which Mike and Terry are doing, then one for John and Eric should come nicely there.’ So casting would very much depend upon the actual shape of the show itself, so everyone got time on screen.

JONES: If you’d written it, you tended to get the first say-so if you really wanted to do it. People would tend to come up with what they wanted to do. And then it would be thrown around; there would be a discussion if somebody else wanted to do it.

IDLE: Casting always came last in everything. That was the brilliance of it being a writer’s show. Once we were happy with the text, then we cast. It was usually fairly easy, like the John parts were obvious – people who shouted or were cruel to defenceless people or animals. Mike and I were usually the ones who could play each other’s parts. Usually people spoke up if they felt they were a bit light in a show; they might sulk until someone noticed, but it was swings and roundabouts, really. Also, we had no girls to sulk or feel left out (i.e., Saturday Night Live) and we would happily grab most of the girls’ parts for ourselves. Serve ’em right, too. Get their own bloody shows! How many men are in the Spice Girls?

Did everyone have an equal interest in performing? Did you all consider yourselves writers first and then actors, or writer/actors?

PALIN: Writer/actors I think, yes. Everybody loved performing, absolutely. Everybody wanted to go out there and put the dress on or whatever! I rarely heard an instance where someone said, ‘Well, I don’t want to do that.’ The great thing was, because we were all brought up in the university cabarets, to get out there and show your own material was all part of it. Writing was merely 50 per cent; the other 50 per cent was the performing of it.

IDLE: Sometimes I enjoyed performing more. In film, I loved the scene in Grail where the guard is told not to leave the room till anyone, etc., because the first time it went right and it’s there on film. It just felt funny – all one take. (Well done, Jonesy. I have to say I love filming for Jonesy.) And likewise in Brian with me as the jailer and Gilliam as the jailer’s assistant. I loved playing both these Palin-created scenes. I wish he had written more. He has an effortless grasp of character for an actor, especially scenes where all three parts are funny. Graham only hiccoughs in the guard scene, but it just adds a wonderful pleasant madness. In Brian, Terry Gilliam makes dark, grunting noises where I stutter away and Michael is this very pleasant lost man who is somehow in charge of these lunatics. It is pure Palin at his finest. They are delightful scenes and my personal acting favourites.

PALIN: Personally, I always enjoyed when you were able to flesh the character out a bit, even within a sketch. I mean, I loved playing the man in the ‘Dead Parrot’ sketch or the ‘Cheese Shop’, because you can give them some sort of character – they’re not just somebody saying, ‘No, we haven’t got this,’ ‘No, we haven’t got that.’ It isn’t just the words, it’s the evasiveness and the degree of evasiveness, and why a man should be that evasive, and what’s going through his mind [that] appeals to me. I really enjoyed getting to grips with characters like that, even within a fairly short sketch.

CLEESE: I remember once that I particularly liked a sketch that either Mike or Terry had written about one of those magazines that is just full of advertisements, so if you wanted to buy a pair of World War II German U-boat commander field glasses or a mountain bike or a garden shed you went to this magazine. And I liked the sketch so much I asked if I could do it – very unusual for me. And Mike had slight reservations about whether I should do it, but they let me. And I didn’t do it particularly well, and I remember discussing it afterwards with Mike, and it was because I was trying to go outside my range – in other words, I didn’t do it as well as he would have done it because he’s better at doing the ‘Cheerful Charlie’ salesman.

But similarly if you’d given Mike that scene where I go on about the Masons and start that strangely aggressive and resentful speech, I think Michael wouldn’t be so good in that area. But it’s much more complicated than you might think because it is not that I am happy about shouting at people, because actually I’m extremely unhappy, I’ve almost never shouted at anyone. I’ve found it almost impossible to do, but I seem to be able to do it on screen. So it’s not like saying, ‘In character you’re the same as you are in everyday life’; that would be utterly simple-minded and untrue, but it just seems to be the case that some people are more comfortable portraying some emotions; I don’t mean that it isn’t utterly connected with their ordinary life, but that it’s not as connected with it as you might think.

Which of the Pythons did you think was the prettiest in drag?

GILLIAM: Prettiest woman, goodness! I don’t know. John was actually pretty nice when he played in ‘The Piranha Brothers’, he’s wonderful sitting in the bar: ‘He knows how to treat a female impersonator.’ John was fantastic in that. John loved it so much I was beginning to have concerns there! The most convincing woman? I think Eric was the best woman. I’m not sure ‘pretty’ came into it. Do you have another adjective?

‘We could have it any time we wanted.’ Chapman and Idle as the Protestants in The Meaning of Life.

‘Least unattractive’?

GILLIAM: I think in Meaning of Life, Eric as the Protestant Wife was spectacular. I just thought that was an extraordinary, wonderful performance. Terry and Mike were always very broad, and Graham was also very broad, but I actually thought the Protestant Wife that Eric played was amazing. Eric’s father died when he was young, so his role model was his mother, and maybe that’s why he was good.

THAT’S MY FLANNEL

Once the shows were assembled, was it easy to see it as a group effort, or was there still a sort of jealous, protective feeling:

‘This is our sketch, that is their material’?

PALIN: I’d like to think we naturally were rooting for every sketch [rather than] anyone wanting their sketches to go down better, although there probably was a little bit of that, but basically you just wanted the show to have laughs all the way through. Putting together that show involved decisions which we’d all taken – the choice of the material, the casting, the links, all that – as part of the group. So if something didn’t work, then yes, it was seen as a failure of the group: ‘We shouldn’t have put that in or cast it that way, set it up in such a way.’ It was very much all group decisions.

And quite interesting, because early on John was undoubtedly the most well-known, [yet] he was very happy to be part of that group – he didn’t want it to be in any way The John Cleese Show, and I would have thought if there was going to be a possible area of difficulty, that would have been one of the problems. John was the ‘star’ before Python; he wasn’t necessarily the star of Python, although he probably was – he was the best known and possibly the best performer. But John didn’t see it that way; John saw it as a group, and Python [assumed] responsibility for everything that went up there, rather than your individual responsibility.

I’m sure at the end of the day there was a bit of, ‘Terry and Mike … ehh!’

SHERLOCK: Graham and John did a bizarre murder sketch for David Frost whereby I think the murderer turned out to be the regimental goat mascot that belonged to the guard who was a suspect: ‘It was the Regimental Goat wot done it!’ It was new in terms of off-the-wall wacky humour. At the time we thought it was hysterical, but most people wondered what the hell the sketch was about. Some of the more surreal sketches they were doing [for Python] had been rejected by every other thing they worked for.

JONES: One of the first sketches was about sheep nesting in trees, which John and Graham had offered to The Frost Report, and the producer Jimmy Gilbert had said, ‘No, no, no, it’s too silly. We can’t do that.’ John’s thing was always, ‘The great thing about Python was that it was somewhere where we could use up all that material that everybody else had said was too silly.’

Did you and Michael also use sketches you had written for other comedians?

JONES: All ours was original material, squire!

Was there EVER any consideration given during the writing process to how an audience would respond to the material?

IDLE: None whatsoever.

PERT PIECES OF COPPER COINAGE

JONES: I think our budget was £5,000 a show. It had been kind of a tight operation. Everything was planned very rigorously. We’d do the outdoor filming for most of the series before we started shooting the studio stuff. We had to write the entire series before we even started doing anything because we’d be shooting stuff for show 13, show 1, or show 2 while we’re in one location, so that while you’re at the seaside you can do all the seaside bits.

PALIN: A lot of the early arguments were just over money; we were paid so incredibly little. So in a sense the BBC committed a lot, they’d given us thirteen shows (which was nice), but they’d taken away with one hand what they’d given us with the other. But on the other hand they let us go ahead and do it!

MACNAUGHTON: Because I was the producer as well as the director, I was able to speak as a producer, so I could say [to the Pythons], ‘That is impossible, we have only got so much of a budget; can we alter this slightly to allow that we don’t go too far over?’ Because you know at the BBC in those days if you went too far over budget the people got rather anarchic. Unless you were exceptionally successful.

PALIN: We presented a script to Ian, we knew what we wanted to do on film and what should be done in the studio, and Ian didn’t really get involved in that aspect of it. On the other hand when we were discussing things like where we would film and how we could best get the effect of a piece of film he would have quite a bit of input. And we’d actually film in Yorkshire and Scotland – that was very often Ian saying, ‘Let’s go out and do that.’

MACNAUGHTON: We used to plan about eight weeks in advance of the series. We knew we wanted an average of, say, five minutes of film per episode (in the first series anyway). The series was thirteen, so we needed time to [shoot] an hour and a half of film. We would plan what sketches or what sequences were better filmed than done in the studio, etc. And as the Pythons went on, they got more interested in the filming side than in the studio side.

Nothing was too ridiculous for us to try. You have a silly sketch like ‘Spot the Loony’ and you happen to be up in Scotland shooting ‘Njorl’s Saga’, and you suddenly think, ‘Wouldn’t it be good to have the loony here in the middle of Glen Coe leaping through the thing?’ These kinds of things happened. They enjoyed all that kind of thing. And it was not particularly more expensive than filming, say, in London because the permission and the fees we had to pay in filming in Glen Coe or Oban or whatever were much less than what we had to pay at the Lower Courts or Cheapside. So the expense was not so great, [and] the opulence of the locations was there, you didn’t have to build them!

GILLIAM: We weren’t doing drama, we were doing comedy, which fell under Light Entertainment, and light seemed to be required constantly so that you could see the joke! Feel the joke! And I just always had a stronger visual sense than [what] we were able to get on those filmings. There would be all these times I’d get in there: ‘The camera should be there.’ Terry would do the same thing; we were always pushing Ian around! I think we were just frustrated because we wanted to film this, too; we were convinced we could do it better. But the BBC didn’t work that way. They would put a producer/director on the thing. And there was a kind of Light Entertainment direction at the BBC which was very sort of sloppy.

I was always frustrated because it didn’t look as good as it should; the lighting wasn’t as good as it should have been. Everything was done so fast and shoddily, there was very little time to get real atmosphere on the screen, or to shoot it dramatically enough or exciting enough. But you churned it out; it’s the nature of television.

We wanted it to look like Drama as opposed to Light Entertainment. Drama was serious; that’s where the real talents hung out!

They ate at a separate canteen?

GILLIAM: It’s almost like that, it always felt like that; they had more money, they can light this stuff. If you’ve got something beautifully lit and the costumes are really great and the set’s looking good and then you do some absurd nonsense, it’s funnier than having it in a cardboard set with some broad lighting. And especially since a lot of the stuff would be parodies of things – if you’re going to do a parody, it’s got to look like the original.

So when we were able to do Holy Grail and direct it ourselves, it looked a lot better. I think the jokes were funnier because the world was believable, as opposed to some cheap LE lightweight. I mean, we approached Grail as seriously as Pasolini did. We were watching the Pasolini films a lot at that time because he more than anybody seemed to be able to capture a place and period in a very simple but really effective way. It wasn’t El Cid and the big epics, it was much smaller. You could feel it, you could smell it, you could hear it.

JONES: Poor old Ian had me [to deal with]. I insisted on going on the location scouts with him and then when we were filming was really sitting in and seeing what Ian was doing all the time. And it was awful for me, too; I used to go out with this terrible tight stomach because we’d see Ian put the camera down and I’d think, ‘It’s in the wrong place, it should be over there!’ So I’d have to go up to Ian very quietly and sort of say, ‘Ian, don’t you think you should put it over there?’ or something like that, and then depending on Ian’s mood at the time, because if it were morning when he hadn’t been drinking he would be very good, but sometimes he got a bit shirty.

Obviously when we were in the studio on the floor you can’t do very much, so Ian had his head then. But in the editing I’d always ring Ian up and say, ‘When’s the editing?’ I could see Ian going, Jesus Christ! Sort of tell me between gritted teeth, and then I’d turn up.

Did he ever purposely tell you the wrong time, to put you off?

JONES: I get the feeling he wanted to do that, but he was too honourable a man! Especially at the beginning, I’d turn up and he’d say, ‘Look, we’ve only got two hours to do this in.’ And I just had to shut out of my head everything about that and say, ‘Well, let’s just see how long.’ We’d end up doing the whole day. I’d see something and I’d think, ‘Ian, we have to take that out, there’s a gap there.’ Usually it was cutting things out, and closing up the show so that it went fast. But it was very hard, because every time I wanted to change something, my stomach would go tight because I knew Ian would go, ‘We’ve nearly had two hours now and we’ve only done ten minutes!’ So we got on a bit like that. And then at the end of the day I’d ring everybody up to have a look at the show. But then as it went on Ian really got very good, actually, because although it was a bit sticky in the first series – and it shows, I think; the first series is not edited as tightly as it could have been – as it went on, Ian got really good at it, and realized that I wasn’t trying to muscle in on his thing; we were just trying to make the best show possible, making sure the material actually came over. So it was very hard for him, but eventually the relationship got really good, and Ian and I worked really well. Ian got very creative, and once you relaxed he got very creative about it, and then came up with a lot of different stuff.

TEN, NINE, EIGHT AND ALL THAT

CLEESE: My memory is that on the whole Ian did not, let’s be polite, interfere much with the acting! We tended to watch each other’s stuff – not all the time because a certain amount of rehearsal is just practice, but we would keep an eye on each other’s sketches, and at a suitable moment somebody might suggest an additional line, or we might come forward and say, ‘I think that bit isn’t working.’ But there was such an instinctive understanding within the group that you probably didn’t even have to say that because people would already know it wasn’t working. It was very much a group activity – not that we were all sitting around desperately focused on each other’s sketches, because people sat around and read the paper and wrote up their diaries.