По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

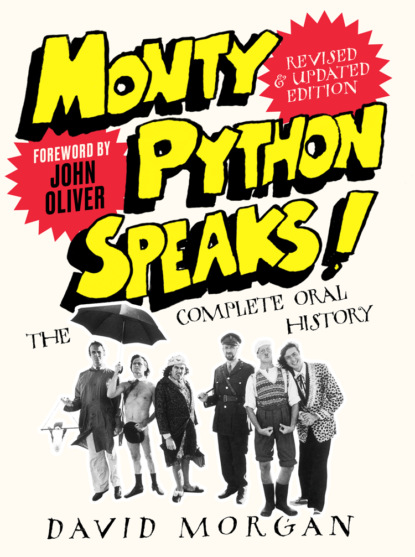

Monty Python Speaks! Revised and Updated Edition: The Complete Oral History

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

And then as far as I remember, we put this to the group and they were grumbling: ‘Yeah, all right, well anyway, let’s get on with the sketch.’

So the first series was very much a fight between the Oxford contingent, if you like, trying to push this stream-of-consciousness into the thing, and the Cambridge group. The Cambridge side weren’t particularly interested; they weren’t against it, but they weren’t particularly interested.

IDLE: We had already tried something like this on Do Not Adjust Your Set and also We Have Ways of Making You Laugh with Gilliam. It was the natural way to go. We were essentially avoiding doing anything that was like the shows we had already worked on or were on the Beeb at the time. Cleese was tired of formats, Jonesy the keenest on experimentation – or at least the loudest in praise of it. But Gilliam was keen to experiment and Graham always anxious to push the envelope: ‘Can we make it a little madder?’ he would say.

GILLIAM: My memory of the first meetings was in John’s flat in Basil Street in Knightsbridge. I just remember sitting up in John’s room a lot and talking and arguing. I think by loosening it up as we did, it then freed us up so that we could have everybody write what they wanted to do, and then we start filtering it through the group’s reaction to the stuff.

DIRECTOR: CLOSE UP, ZOOM IN ON ME

Ian MacNaughton was an actor before becoming a director at the BBC in 1961. After several years toiling in the trenches of the Drama Department, he was offered a chance by the then–head of comedy to direct programming for the Light Entertainment Division.

IAN MACNAUGHTON: I asked the head of comedy why did he ask me and he had a very funny answer: he had been in Studio 3, where they were doing a Light Entertainment show, and someone came to him and said, ‘Do look into Studio 2, where they’re doing a drama series called Dr Finlay’s Casebook – they’re getting more laughs in there than you’re getting out here!’

Dr Finlay’s Casebook was a very turgid drama, it was too dramatic, and I arranged with the script editor to write something funny, a small scene before the end in which we have a bit of funny to heighten the tragedy at the end of the piece, and so this came about that way. The head of comedy did look in, and the next day he asked would I like to do the funnies? And I said, ‘Yes, very much!’

And so I joined the Light Entertainment branch and was immediately handed a Spike Milligan show, Q5. Now Spike Milligan is a rather eccentric comic clown, and I don’t think anybody else was very happy to work with him – he was a very undisciplined man – but we did the show and it was a reasonable success, and the Python boys had seen this show going out and they asked the BBC if they could have me direct their first series. The BBC said yes, and so that’s how we started together.

IDLE: In fact, I hardly remember Barry Took being involved at all; the key meeting was with MacNaughton. He was directing Spike and we all liked the mad direction those shows were going in, so we met him and he seemed loony enough, so we said, ‘Okay’. He couldn’t do the studio direction for the first four (though he did do the exterior filming), so John Howard Davies did those. He was more in control and a bit less of a loony, and I found him very helpful on the early acting because he was an actor – indeed, he was Oliver Twist in David Lean’s movie!

Ian’s great brilliance was that he didn’t get in the way.

PALIN: We had a few battles over a director, because in early meetings some of us had found John Howard Davies to be completely wrong for the ethos of Python; he represented the most conventional, conservative side of BBC comedy. And there was this mad cat Ian MacNaughton, who seemed to represent the free spirit that we wanted. I remember a couple of fights over that – not fights, but sort of polite disagreements; there were some tensions over that. John Cleese was very much a John Howard Davies man; in fact, he used John Howard Davies for all of Fawlty Towers. And Cleese was guarded about Ian MacNaughton; he didn’t like Ian because he drank, he was sometimes out of control, he was a mad incomprehensible Scotsman, and Cleese saw him allying with the sort of wild, passionate [Pythons] on the other side. But in the end we got Ian MacNaughton.

I think probably we did need somebody like that who was going to be responsive to our ideas. John Howard Davies was a nice man, and he did four shows (although Ian always directed the film sequences). Davies found that it wasn’t a natural sort of programme for him to do, whereas Ian was very responsive to all our ideas, especially if we had him do something different. He would be at home with the anti-authoritarian aspect of it, which was something he liked and rather identified with, whereas I think John Howard Davies was much more identified with BBC structure as it was then. He wasn’t the kind to be taking risks; he was an organization man.

Ian would take some risks. Ian was always somebody outside the organization, probably because of his lifestyle: he was a Scottish actor, he didn’t see himself as a metropolitan London man at all, which helped, because Python was never metropolitan. As Barry Took once pointed out (which was very acute), all of the Pythons come from the provinces and none of us were Londoners. We all saw London in a sense as slightly the enemy, a citadel to be conquered, and of course Ian was definitely from Glasgow – he had this anti-metropolitan attitude, which helped us.

CLEESE: Well, I suspect my view on this is rather different from the others’, because I thought John Howard Davies was very good. But he wasn’t as skilful with his cameras as Ian was; Ian was a very visual director. John was a very, very good judge of comedy. He wasn’t a tremendously verbal person, but his instincts were extraordinarily good, and he was very good at casting. So I had a lot of respect for him to do comedy, but I know that the more visually oriented people felt that the show took a big step forward (from the point of view of form as opposed to content) when Ian took over. And I thought Ian was pretty good, but I never thought he was particularly expert in the direction of comedy. He was always more bothered by how he was going to shoot it than he was about whether the sketch was really working or not, whereas John Howard Davies’ focus on just those first four shows he directed was more towards the content, even if he didn’t actually shoot it so well.

GILLIAM: Ian had worked with Spike Milligan, that’s why we liked the idea of Ian coming in. He wasn’t forced upon us; we lucked out. Ian worked, because he put up with things. Everybody pushed him around. I like Ian a lot, I mean just his personality.

Ian held it together, but we would be constantly going, ‘Shit, why is the camera on that?’ But I think anybody would have been beaten up by us in the same way. He trotted on, he did it. If it had been left up to us, we couldn’t have done it, there’s just no way. We thought we could, but I’m sure we couldn’t have!

Ian MacNaughton directing Palin in ‘The Cycling Tour’.

TAKE-OFF (#ulink_a9b3adbb-d920-5d5d-9bc4-e47c99caf76b)

LET’S GET THE BACON DELIVERED

As the group prepared for the first series of Monty Python’s Flying Circus (which began recording in August 1969), the notion of applying a stream-of-consciousness style to the show’s content and execution was accepted.

PALIN: Certainly Terry Gilliam provided an example of how you could do stream-of-consciousness comedy in his animations, which he’d done on Do Not Adjust Your Set. We thought those were remarkable and a real breakthrough; there was nothing like that being done on British television. We loved the way the ideas flowed one into another.

Terry Jones was very interested in the form of the show, wanting it to be different from any other – not only should we write better material than anybody else, but we should write in a different shape from any other comedy show. And probably Terry Jones and myself saw (or were easily persuaded) that Gilliam’s way of doing animation maybe held a clue to how we could do it. It didn’t matter if sketches didn’t have a beginning or end, we could just have some bits here or there, we could do it more like a sort of collage effect. I remember that everyone was quite enthusiastic about this, but it would have almost certainly come from Terry Gilliam, Terry Jones, and myself.

GILLIAM: I think it was more like saying ‘no’ to certain things, and the first thing was ‘no’ to punchlines, which is a really critical thing. We’d seen Peter Cook and Dudley Moore doing so many really great sketches where they traditionally had to end with a zinger, and the zinger was never as good as the sketch. The sketch was about two characters, so in a sense it was more character-driven than plot-driven, [but] time and time again you’d see these really great sketches that would die at the end – they wouldn’t die, but they just wouldn’t end better [than] or as well as the middle bits. So very early on we made a decision to get rid of punchlines. And then Terry Jones was besotted with this cartoon I had done, ‘Beware of Elephants’, [in which] things flowed in a much more stream-of-consciousness way. Terry thought that was the shape that we should be playing with.

Spike Milligan had been doing some amazing things just before; his Q series in a sense really freed it up, playing with the medium of television, admitting to it being television, and commenting on that. We just continued to do even more of that than he had done, but once we agreed on the idea of not having to end sketches, and having things linked and flowing, it allowed us to get out of a sketch when it was at its peak, when it was really still good; we would laugh when it was funny and it would move on when it wasn’t funny. That also immediately made a place for me; it sat me in the middle, connecting things.

IDLE: We were young, and doing a show we would be in charge of for the first time. There were no executives. This freedom allowed us to experiment without having to say what we were trying to do – indeed, we didn’t have a clue what we were trying to do except please ourselves. This was the leitmotiv: if it made us laugh, it was in; if it didn’t, we sold it to other shows.

THIS YEAR OUR MEMBERS HAVE PUT MORE THINGS ON TOP OF OTHER THINGS THAN EVER BEFORE

JONES: The way we went and did the shows is, first of all we’d meet and talk about ideas. And then we’d all go off for like two weeks and each write individually or in our pairs. Mike and I tended to write separately and then get together, read out material to each other, and then swap over and mess around like that. So at the end of two weeks we’d all meet together, quite often downstairs in my front room or dining room, and we’d read out the stuff. That was the best time of Python, the most exciting time, when you knew you were going to hear new stuff and they were going to make you laugh.

GILLIAM: And so you get a sketch where John and Graham had written something and it got that far and it was really good, but then it just started dribbling; well, either you stop there, or maybe Mike and Terry would take it over with some ideas to patch it up. I always liked the fact that there was just a pile of material to start with all the time, because everybody would go their separate ways, come back, and there would be the stuff, [sorted into] piles: we all liked that pile of stuff, [we were] mixed on that one, we didn’t like that one.

You had to jockey for position about when and where a sketch was going to be read out, which time of the day; if it came in too early it was going to bomb. And you knew that if Mike and Terry or John and Graham had something they wanted to do, they wouldn’t laugh as much [at the others’ material]. And I was in a funny position, because I was kind of the apolitical laugh; I was the one guy who had nothing at stake because my stuff was outside of theirs.

IDLE: It seems to me since all comedians seek control we were a group of potential controllers. Obviously some are more manipulative than others, or cleverer at getting their own way. Cleese is the most canny, but everyone had their ways. Mike would charm himself into things. Terry J. would simply not listen to anyone else, and Gilliam stayed home and did his own thing since we soon got tired of listening to him trying to explain in words what he was doing.

The writing was the most glorious fun. We would go away and write anything at all that came to mind for about two weeks, then get together for a day and read it all out. Then, what got laughs was in, and people would suggest different ways of improving things. This was very good, this critical moment. Then we would compile about six or seven shows at a go, obviously moving things too similar into different shows, and then noticing themes and enlarging on strands of ideas and then finally linking them all together in various mad ways that came out of group thought. This, as far as I know, was an original way of working which hasn’t been tried before (or since) and was unique to Python. Gilliam was there, too, as an individual non-writer, and whenever we were stuck we would leave it to him to make the links, which he would do.

PALIN: By [the time Python started] Terry and I were working separately; there’d be a couple of days just writing ideas down and then we’d get together, talk about things, so some of the sketches that were Jones and Palin would be entirely Jones or entirely Palin, but the other would add lines here and there. So it was good in that way; we were writing separately perhaps more than we had before.

I think we were all (certainly to start with) anxious to be generous to each other, and give each other time and due consideration. You know, it was important that everybody write something that was funny, otherwise it would have been very difficult, and generally I think everybody did. Spirits were pretty high. It was not difficult for some of those sessions to be happy at the way things were going because the material was fresh; we could chop stuff around and not be confined to the shapes of previous comedy shows; we were really getting some very nice, new, surreal stuff together.

The best sessions I remember were when we were just putting the whole lot into a shape, into a form. Certainly there would be some sketches that were still very conventional, and others would just be fragments. We’d have read the stuff out and then we’d try and put them together, follow this by that, and then, ‘Why don’t we introduce that Gambolputty character and then try to say the name “Gambolputty” later in the programme,’ something like that. ‘Yes, that’s right, he can come in and we do this, and then the Viking can come in and sort of club him or something.’ The idea of having characters in quite elaborate costume just coming in to say one word – ‘So’ or ‘It’s’ – in the middle of a bit of narration, all that seemed very fresh. We enjoyed that feeling of being able to clown around the way we wanted to. And the material coming in was (we felt) pretty strong and really unusual. Things like the man with three buttocks seemed just wonderful, especially because it was done in this very serious mode – bringing the camera around to see this extra buttock, and he’d say, ‘Go away, go on!’ – this man who’d agreed to go on television because he’s got three buttocks then getting rather sort of prudish about any talk about buttocks! Really nice ideas.

How did your own work habits change as you started working as part of a larger group?

PALIN: I wasn’t used to working like that, but basically I have such respect for the other writers. I mean, Graham and John were just writing the best sketches around at that time, so to be able to give them [something] they would then take away, one had absolute confidence. And the same usually with Eric; we’d worked together on Do Not Adjust Your Set. There was really, as far as I can remember at that early stage, very little wastage. I mean, sketches didn’t just disappear if someone screwed them up; it would happen: someone would take something away and it just didn’t work out, and we would similarly take other people’s ideas. It didn’t happen that much. And in the early shows John and Graham were still writing ‘sketchey’ sketches; ‘The Mouse Problem’ or ‘The Dead Parrot’. They came fully formed, four or five minutes of stuff which didn’t need to be changed, so very often it was just the links that would be our group. There wasn’t an awful lot of cross-writing.

If anything strengthened Terry and myself as a team, I think we felt this was highly competitive in a way it hadn’t been before. We’d send sketches to Marty Feldman or The Two Ronnies and someone somewhere would take a decision and you get the word back – ‘We love this, we don’t like this’ – we wouldn’t be in the room at the time, we wouldn’t be part of that process. Here, because we were writing the whole thing and performing it ourselves, the atmosphere was quite competitive. We felt we really had to get our ideas really right before they were read.

That was an interesting thing. We’d have a discussion the day before: ‘Shall we read this, shall we read that?’ Terry and I always wrote more than anybody else – a lot of it was of a fairly inferior quality – but we didn’t want to read the group too much because there was a certain point where you could see people getting restless: ‘And what have you got?’

‘Oh, we’ve got another six sketches!’

‘[Huffing] All right, we’ll have some coffee and then read these next six sketches for Mike and Terry!’

You had to be a bit careful about how you sold your stuff!

Were you at a disadvantage because you didn’t have a writing partner helping to ‘sell’ your material?

IDLE: No, no. The other teams had two people to laugh. But I had the advantage of working with myself, a far more interesting partner!

Comedy writing is done often in pairs, but I always found it boring. I occasionally worked with John (‘The Bruces’, Australian philosophy professors with a passion for beer and a distaste for ‘pooftahs’; ‘Sir George Head’, the mountaineering expedition leader with double vision) and a bit with Mike. But I like writing by myself.

Last time I looked, writing was always largely a solitary occupation. I like to write first thing in the morning and then stop when I feel like it. I don’t like to talk. I don’t much care for meetings. My favourite form of collaboration is with a partner on email who bounces back my day’s work. I think you need partners for shape, notes, and criticism.

CLEESE: I was the one who was having to write with Graham. Now I thought early on, before Graham’s drinking was any sort of a problem, it would be much more fun if we occasionally broke up into different writing groups; we could keep the material more varied. To some extent there was a Chapman/Cleese type of sketch (which was usually somebody going into an office of some kind and probably getting into an argument in which there would be quite a lot of thesaurus-type words), whereas Mike and Terry would nearly always start things where some camera would pan over Scottish or Icelandic or Dartmoor countryside and afterwards would get into some sort of tale. And Eric’s was largely one man sitting at a desk talking to the camera and getting completely caught up, as they say, disappearing up his own arse.

The result of this switching was that Eric and I wrote ‘Sir George Head’, and Michael and I wrote about Adolf Hilter standing for Parliament in Minehead. I thought those were rather successful. But there was a general resistance to that switching around, and maybe it was partly that nobody else wanted to write with Graham. I think he was regarded as my problem, which naturally I thought was a little unfair. But I think that Terry was always very keen to write with Michael, that it was quite difficult for him to let go of that. And Eric liked to write on his own because it gave him such autonomy – for instance, he could write when he wanted to. There are many good things to be said for that, because if you write with someone else it becomes an office job.

So I guess Terry wanted to reclaim Michael, and Eric maybe liked being on his own, and Graham was my problem; I guess that was the dynamic.

Did you and Terry ‘perform’ your sketches for the group at these meetings?