По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

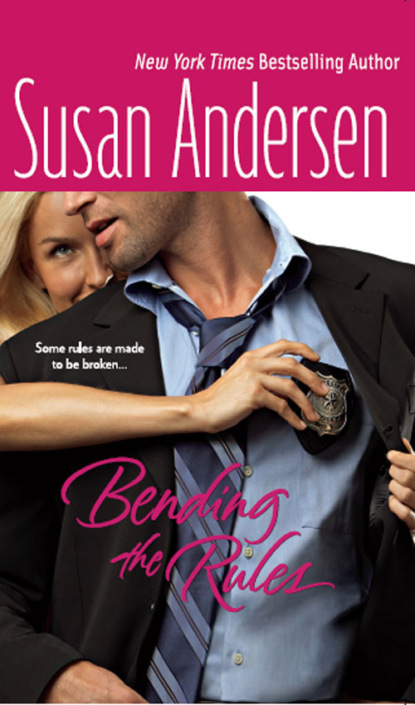

Bending the Rules

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Then Murphy said dryly, “I’m gonna take a wild stab here and speculate we’re not still talking about a bunch of merchants deciding to vote down the Babe’s proposal.”

Burying his head in his hands, Jase groaned.

He felt Murph rub rough fingers over his hair.

“One of these days,” the old man said gruffly, “I’d like to see you give yourself a break and realize you’re not like your dad or grandpa or Joe.”

“That’s never going to happen…because I am.” Dropping his hands to the tabletop, he raised his head to look at the old man. “I’m a goddamn de Sanges male,

which is a lot like being a recovering alcoholic—I’m one act away from being just like the rest of the men in my family.”

“That’s bullshit, and you oughtta damn well know it by now. But, no—you’re too fucking stubborn to take your head outta your butt. You have never knocked over convenience stores. You have never kited checks or destroyed bars in a drunken brawl. And I’m guessing now is probably not a good time to tell you about this, but I’m going to anyways. I got a call from your brother today, looking for you.”

Everything inside him stilled. “Joe’s out on parole?”

“Looks like.”

“Shit.” Jase laughed without humor. Then, spreading his fingers against the faux wood, he lowered his head again and thunked it once, twice, three times against the tabletop. “I guess I’d better get in touch with him quick then, hadn’t I? Because God knows he won’t be out for long.”

Chapter Three

Holy shitskis, that “Be Careful What You Wish For” thing is no joke. Just when things were starting to settle down and I was finally getting that man out of my head…this!

“SHARON, YOU want to come take a look?” Poppy twisted around on her perch near the top of the stepladder to look for the coffee-shop owner.

The woman popped her head out of the kitchen. Brushing flour from her hands against the white apron tied around her waist, she stepped into the retail area and studied the blackboard, closely inspecting the updated menu Poppy had just completed. Then she smiled. “Lookin’ good.”

“Excellent.” Poppy packed up her case of colored chalks and climbed down off the ladder. She slid the container into her big tote, which she’d left by the register, then folded in the ladder’s legs and tipped it carefully onto its side in the narrow area behind the glass bakery case until it was parallel to the floor and she could get a grip on it with both hands. Glancing out the door at the pale glow of daybreak beginning to lighten the eastern sky, she said, “I’ll just go put this back in the closet, then clean up and get out of your way.”

“I took a blueberry coffee cake out of the oven about ten minutes ago,” Sharon said. “You have time for a slice and a cuppa joe? My staff’s going to start trickling in pretty soon and I don’t know about you, but I’m ready for a break.”

“That would be great.” As if to demonstrate its appreciation, her stomach growled and, patting it, she laughed. “Don’t tell my mother, but I skipped breakfast this morning.”

She maneuvered the ladder through the kitchen to the big utility closet by the back door, where she stored it away. Then she washed the multicolored layers of chalk from her hands and joined Sharon at a table. They visited over cups of full-bodied coffee and luscious, still-warm cake.

She didn’t linger long after the snack was consumed, however. She still had three other boards to do this morning at sites scattered from Madison Park to Phinney Ridge to the Ballard neighborhood where she’d grown up, and they needed to be completed before the businesses were open to the public.

When she finished the last job, a deli just off Market Street, she looked at her watch. She’d planned to drop in on her parents but schools were closed for a teachers’ “professional development” day, she had a date with some kids in the Central District—or the CD, as it was called by native Seattleites—and she had to stop by the mansion first. So with a regretful glance in the general direction of her childhood home, she steered her car toward the Ballard Bridge.

She lucked into a parking space on the block below the mansion on the steeply pitched western slope of Queen Anne and, getting out of her car, she paused to look up at the house.

The sunroom that had been scabbed onto the front of the edifice was now whittled down to a size and style in keeping with the rest of the structure and the Kavanaghs had repaired the facade to match the original. Her artist’s soul smiled to see the elegant bones restored to the early-twentieth-century mansion. The sound of hammers, pithy obscenities and male laughter coming from the kitchen as she approached the back door elicited yet another grin.

She let herself into a room filled with buff guys wielding power tools. Well, okay, only one of the four men in the gutted kitchen was actually operating one. As Devlin Kavanagh’s drill whined into silence and he and his brothers looked over at her, she inhaled a deep breath, then blew it out with theatrical gusto. “I love the smell of testosterone in the morning!”

Raising his black eyebrows toward his Irish-setter red hair, Dev drawled, “According to Jane, babe, you wouldn’t know what to do with testosterone in the morning.”

“You are so full of it, Kavanagh. Janie would never rat me out—not even to you. And watching all this tool-belt activity does make my little heart go pitty-pat. It’s. Just. So—” she batted her lashes at Dev and his brothers “—manly.”

They laughed and went back to work. She headed upstairs.

Where she found herself wandering the finished rooms, thinking about the videotape Miss Agnes had left for her, Ava and Jane to view at the reading of the will almost exactly a year ago. In it the old woman had said how much the three of them had come to mean to her over the years. And she’d told them in that foghorn voice of hers that she realized they’d have to sell the mansion—but it was her wish that each would carry out one final request from her in getting it ready. Poppy sure wished, not for the first time, that she understood what it was Miss A. had had in mind when she’d requested that Poppy be in charge of the decorating part of the renovation.

The old woman had been so good to the three of them, amazingly canny when it came to knowing what each one needed, then seeing to it that they got it. For Jane and Ava that had meant a modicum of parenting to fill in the gaps left by the always dramatic self-absorption of Janie’s folks and the benign indifference of Ava’s. For her it had meant having her passion for color indulged. Miss A. had done what few other adults would—given a young girl a paintbrush and the paint color of her choice and trusted the kid not to make a huge mess out of her mansion. And in the matter of the dining room, she’d even allowed Poppy to choose window treatments that let in light where before heavy draperies had kept it out. But that was a far cry from decorating the entire place.

“Omigawd.” She stopped dead in the upstairs hallway. “That’s it.”

Grabbing her cell phone from her tote, she was punching in an auto-dial number even as she rushed from the mansion. “I finally figured it out!” she crowed to Ava as she strode back to her car. Holding the phone to her ear, she adjusted her slipping tote on her shoulder and almost tripped over a raised slab of sidewalk where an ancient Douglas fir’s root had pushed it up.

“I was making Miss A.’s request way too complicated. I thought she’d completely overestimated my talents and wanted me to act as a big-time interior decorator.”

“You could do that,” Ava assured her.

She laughed. “You’re a true and loyal friend and I love you for it. But I design menu boards and the occasional greeting card—”

“One of which got picked up by Shoebox!”

Yes, that was a stroke of luck she was still dancing in the streets about—that she no longer had to scramble to come up with the rent check the first of each month. “But, face it, mostly I do catch-as-catch-can low-end commercial stuff for whoever I can convince to hire me and fast-talked my way into a couple of grants to turn on underprivileged kids to art. I’m sure as hell no interior designer.”

She grinned like a deranged jester. “But that’s what I figured out, that Miss A. didn’t intend me to be. Jane actually tried to tell me this last fall, but my thong was in a twist at the time because I thought she was about to blow the deal I’d made with the Kavanaghs, so it didn’t really register. But I think all Miss Agnes wanted from me was precisely what I was always bugging her to let me do—rip down all those gawd-awful drapes that are blocking out the light, give the rooms a fresh coat of paint and new window treatments and maybe stage it the way Realtors do these days with a few of her nicer pieces of furniture and the odd collectible.”

“That sounds reasonable. But, girl, don’t underestimate yourself, because you’ve already done so much more. You found us the Kavanaghs and negotiated a lower bid in exchange for the publicity they’ll get, and you’ve been the one handling ninety percent of the bills—when all you really want to do is work with your kids.”

That made her flash on the three boys she wouldn’t have the opportunity to work with, which made her think about de Sanges, which, frankly, she’d been doing far too often in the past week and a half since running in to him again at the merchants’ meeting.

Her chin lifted even as she drew herself up to her full height. Well, she was going to quit doing that, starting this instant.

“You’re thinking about them, aren’t you?” Ava said.

Poppy stumbled. “What?”

“Those boys That Man robbed you of. You’re thinking about them.”

“Uh, yeah.” But not as much as the man himself, she admitted guiltily.

“The bastard.”

Her sentiments exactly. She just wished she could shake him from her thoughts, that the image of him, all long and lean and imbued with a sexual energy that whispered to her own, would get the hell out of her head. And in truth, the more time that passed since their encounter, the better she was getting at not thinking about him.

Arriving at her car, she said goodbye to Ava, tossed her tote into the backseat and headed for the CD.

Like the rest of Seattle, the Central District was undergoing the boom of town houses or mixed retail and condominium construction that was changing the face of the city. This neighborhood was changing more than most, however, because in addition to the relentless urban-density building going up all over town, the past decade had seen the area transform from a primarily African-American neighborhood to one with a more integrated mixed-race demographic—a change not necessarily embraced with enthusiasm by the residents who’d been here the longest.

She pulled in to the community center lot on East Cherry, parked and unloaded her easels and supplies, making several trips to haul everything into the room assigned her.

She was a little early so she got started setting the easels up and putting out pencils, brushes, palettes and tubes of paint for her class. She thought of the very first time she’d done this and smiled. Miss Agnes had volunteered her when she’d heard the DAR was looking for someone to teach an art class for one of their charitable endeavors. Poppy had been less than thrilled at the time. She was twenty-seven, scrambling to make a living on her own terms, and she’d had to stretch her schedule to fit it in.

Then she’d met the kids.