По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

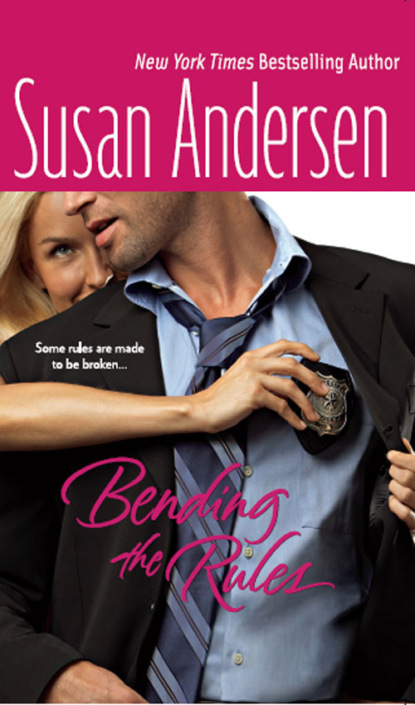

Bending the Rules

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

She couldn’t believe the bluff that had come out of her mouth. As if she called in personal favors from the mayor—and people of even more influence—all the time!

A sputter of hysterical laughter escaped her. As if, indeed. No, the only one in the Sisterhood with political clout was Ava. Who, it turned out, had talked to her uncle Robert, who played golf with His Honor the Mayor most Wednesdays—and all without so much as a hint to Poppy that she planned to do so. Poppy had been as surprised as de Sanges to hear from the mayor’s office that her proposed project was on after all. And although she’d been thrilled at the thought of having an opportunity to help those three kids, she hadn’t been lying—she had felt kind of guilty about Ava going over the detective’s head for a second time. But only until he’d opened his mouth and threatened to intimidate the teenagers. That had shot her empathy straight to hell.

Yet with or without the sympathy factor, she really, really wished she hadn’t touched him.

Because. Lord. Have. Mercy.

She didn’t know what it was about him, but she only had to lay eyes on him and she got such a visceral reaction she didn’t know what to do with herself. She hadn’t felt this strongly about Andrew, and she’d had a three-year relationship in college with him. Such an unprecedented response to a guy she didn’t know and didn’t much like the little she did know shook her up. And that pissed her off. Never a stellar combination, which she had proven by promptly getting off on the wrong foot with him the minute she’d opened the door and seen him on the other side.

She’d thought she was being so clever to treat his arrogant high-handedness over her door chain as if it were a concerned command from her father.

But it hadn’t been clever at all; it had been stupid. Because she’d looped her arms around his neck and she had damn near whimpered at the heat that pumped off his long, hard frame, at the starch and soap scents she’d smelled emanating from his collar that made her want to bury her nose in his neck. His angular jaw had been bristly beneath her fingertips, making the full cut of his lips look contrastingly soft—until they’d suddenly gone hard with some unnamed determination. Whereupon she’d all but leaped out of range like a scalded cat.

She hoped he hadn’t noticed, but he didn’t strike her as the type who missed much.

Her subsequent embarrassment, combined with his unemotional threat against her teens, was undoubtedly what had given her the stones to look him in the eye and lie like a politician.

But, oh, she was torn about having her proposal suddenly accepted. Half of her was thrilled at this opportunity to reach the three teenagers.

The other half thought she was freaking nuts to put herself anywhere in de Sanges’s vicinity.

Oh, no. The latter thought put a firm halt to the low-grade panic she’d been experiencing ever since she’d opened her mouth and started threatening him, and her spine snapped straight. Oh, no, no, no. She was neither weak-willed nor easily pushed around, and the idea that she should be wary of or intimidated by a little one-on-one time spent with the detective put her back up but good.

For God’s sake, she wasn’t some impressionable fourteen-year-old ruled by her hormones. Yes, he was dark and steely and, okay, the power of attraction she felt was formidable. But she was a big girl, one who was motivated to preserve—and hopefully enhance—the well-being of those kids. And contrary to what de Sanges might believe based on tonight and the first time they’d met, she actually did know how to act professional.

So he had better just watch his step. Because she was a woman with a mission.

But one who was going to be very careful never to get within touching range of that man again.

Chapter Five

And I’m supposed to be an artist, with an eye for detail. Some eye. Because the whole Cory-being-a-girl thing—I sure didn’t see that one coming!

FOURTEEN-and-three-quarters-year-old Cory Capelli pulled her newsboy cap down low, flipped her father’s battered leather jacket collar up and veered away from the group she’d been hanging with on the Ave in the U district. She liked catching up occasionally with other graffiti artists and taggers to hear the latest gossip about who was doing what and listen to everyone one-up each other’s lies. But she did her best work alone.

It was a policy she should have remembered before she hooked up with Danny G. and Henry Whatshis-name two weeks ago. Danny alone would have been fine. He did some of the best storytelling graffiti around, and Cory considered herself more of an artist than a tagger. She might not style elaborate wall paintings but her tag, CaP, was a work of art in its own right with its fat, two-dimensional, multicolored letters and her trademark cap hanging from the lowercase a. She considered it a world removed from scrawling quick and dirty chicken scratches on bus-stop signs or buildings or messing up someone else’s work. She’d been working on some graphic novel-type illustrations in her sketch pad at home, but she hadn’t worked up the confidence yet to give them a public try. Which was why she’d wanted to team up with Danny G.

Henry, on the other hand, was one of the chicken scratchers. So when he’d attached himself to their plan to cover a block of buildings together, in a neighborhood they weren’t familiar with, she hadn’t known how to say that didn’t work for her.

She definitely needed to learn that, whatchamacallit…assertiveness stuff. Because just look where her silence had gotten her. Could you say busted? The three of them were now scheduled to meet some do-gooder tomorrow morning to paint over what they’d done. Whoop-de-do, Cory thought, spotting a nice wall and melting into the space between the dentist’s office hosting it and the jewelry store next door. Like that was how she wanted to spend her Saturday morning.

Still, it beat getting a record and being sent to juvie, which would just finish the job of Mom’s already broken heart. And Cory got it—she really did—that relatively speaking, she and Danny G. and Henry had lucked out with those people whose buildings they’d tagged. Well, Henry had tagged. He’d managed to scrawl his crap over every workable surface before she or Danny could so much as pull out a can of paint.

Okay, that wasn’t quite true. They’d both had their cans out when the guy from the store across the street had busted them. Henry might have beaten the two of them to the neighborhood but it wasn’t as if they hadn’t been there to do the same thing he had done—if you discounted the talent factor, since even with their dominant hands tied behind their backs, either one of them would have done a helluva better job.

But the point was, they’d still lucked out with those store people. Because while the merchants had called in the cops, they’d refused to press charges until they had a chance to discuss among themselves what to do with her and the boys. So this cleanup gig was better than the alternative.

But not by much.

And the thought of it was putting a heavy-duty crimp in her night. She was bummed out, it was late, and foot traffic from U-Dub students had dwindled everywhere but around the area’s taverns and clubs. That last part was actually a good thing, since it skewed her odds toward the not-getting-caught end of the spectrum. But it felt isolated and lonely and rain clouds were starting to blow across the moon-free sky. In the little bit of light that managed to penetrate between the buildings from the corner streetlamp, she found herself gazing listlessly at the expanse of smooth buttercream paint in front of her.

Giving herself a mental shake, she then shook her aerosol can of Patriot Blue, absorbing the comforting sound of the bead rattling around inside. By rights she oughtta be all pumped up at finding a virgin wall like this one.

Only…

She had zero vision in her head as far as putting a fresh spin on her tag went. Usually she had all kinds of ideas. But she was tired of just doing the same letters over and over again, and she couldn’t drum up a lick of enthusiasm for the project, no matter how rare it was to find a clean wall.

So she might as well go home. In light of the way she’d be spending her Saturday tomorrow, it was pretty dumb to be out here pushing her luck in the first place. Plus Mom would be getting off work in about an hour and she’d freak if she knew Cory was out this late.

The knee-jerk guilt was immediate, but so was the defiance she pushed it away with. Hey, it wasn’t as if she didn’t stay in like a good little Girl Scout dang near every weeknight. She even studied so that she wouldn’t have to see the sad look she’d put on Mom’s face last spring by bringing home a truly in-the-toilet-type report card.

But the weekends were a different matter. They just seemed to stretch without end, what with Mom working two jobs and the fact that they’d only moved here from Philly a couple of months ago. Midyear changes at school sucked—she’d like to see anyone, except maybe one of those so-perky-you-wanted-to-smack-’em cheerleader types, make instant friends. And a girl had to have some fun.

There’d sure been precious little of that since Daddy was killed.

Grief, hard and sharp, sliced through her defenses, and she doubled over, her arms wrapped around her middle. But this wasn’t the place to give in to it and she pulled herself upright. Still, she had to get out of here.

She was slipping out from between the two buildings when she heard glass breaking, so close it made her jump. There was a shout from within the store next door. Then the report of a gunshot. It was a sound that defined her nightmares and she froze in the deep shadow of the dentist’s office doorway, cold sweat trickling down her sides.

A strident alarm started whooping and she made herself move, shimmying up the rough brick that formed a facade at the front of the building. It seemed like an eon but was probably only a few moments before she hooked her elbows over the edge of the one-story office’s cantilevered roof and swung herself over its lip. She lay there on her back for a moment, panting and struggling to slow her heartbeat. Then she slowly rolled onto her stomach and pulled herself by her elbows to the back edge nearest the north-side jewelry store, knowing she should have simply beat feet while the beating was good, but sucked into a bad decision once again by her damn impulsiveness and never-ending curiosity.

From her vantage point she watched kids pour out of the shop’s back door and realized the stories she’d thought a couple of taggers had been making up must be true: there was a youth gang robbing city jewelry stores. Given that most of the kids looked young even to her, she couldn’t imagine they’d come up with the idea on their own.

The thought had no sooner flitted across her mind than a man stepped out behind them, shoving both a gun and what looked like a black hood in the waistband of his slacks. He paused beneath the dim light that shone over the door, but with the brim of his porkpie hat throwing his face in shadow she couldn’t make out his features. And that was just fine with Cory, since the most painful lesson she’d learned in her life was that the wrong kind of knowledge could kill you.

That’s how it had worked with her dad.

“Move your asses,” the man growled, and the kids scattered in six different directions. “Fucking amateurs,” he muttered and lit a cigarette as he pushed away from the door.

And, oh, crap. The flame of his Zippo briefly illuminated his face.

She knew him. Well, she didn’t know-him know him, but she recognized who he was. She’d overheard someone saying he was, like, the muscle for some local crime boss whose name she couldn’t recall. But she knew he had a bad reputation. And she really, really didn’t want to bring herself to the attention of the top dawg or his henchman. Not when it was obvious the Hench had just shot someone.

But she must have made some sort of noise or moved without realizing it, because even as Muscle Boy was stalking purposefully down the passageway between the two buildings toward the street, he looked up.

Straight at her.

Cory’s heart stopped and for a moment she merely gawped. Seeing his hand go for the gun in his waistband, however, unfroze her but quick and, scuttling backward, she scrambled to her feet and raced across the rooftop, leaping up onto the roof of the south-side building with strides long and sure even as her mind screamed in panic. Her daddy had been a track star way back in his high-school years, and he’d taught her to run practically from the time she could walk. He used to say she was the son he’d never had and the daughter he’d always wanted.

But she couldn’t think about that now because it made her knees weak. Shoving all thoughts of her family aside, she sprinted across the second building and up onto a third. This one had a working roof with heat or air shafts or whatever they were sticking out, and a little shedlike structure with a door that led to the building. She came to an abrupt halt. She couldn’t simply keep going—at least not without trying to think it through. The Hench hadn’t come up onto the dentist’s roof after her, so he was no doubt headed straight for the last building to await her descent. At least she hoped that was what he would do. Because her plan was to bail midblock. She sped over to the door and reached for the knob.

It was locked. But there was a fire escape going down the back of the building. Cautiously, she approached it and peered over.

And damn near wet her pants. In the millisecond before she jerked back again she glimpsed Muscle Boy—a big, ugly boogeyman of a guy—pointing his gun at her in a two-handed grip.

A gun that he’d already proved he wasn’t shy about using. The crack of it discharging at her in the next second sounded louder than thunder.

Almost simultaneous with the report, the bullet hit high on the air vent thingie behind her and ricocheted off. She managed to bite back the girlish scream bulging the back of her throat, but it was a close thing. She’d learned a long time ago to dress like a boy when she went out tagging. It was just safer and even with the cops and the store owners who’d busted her two weeks ago, she’d stayed in character. She hadn’t claimed to be a boy, but she was tall and she knew how to walk and talk like one when she needed to. Plus Cory was one of those names that could belong to a boy or a girl and hers even had the more boylike spelling.