По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

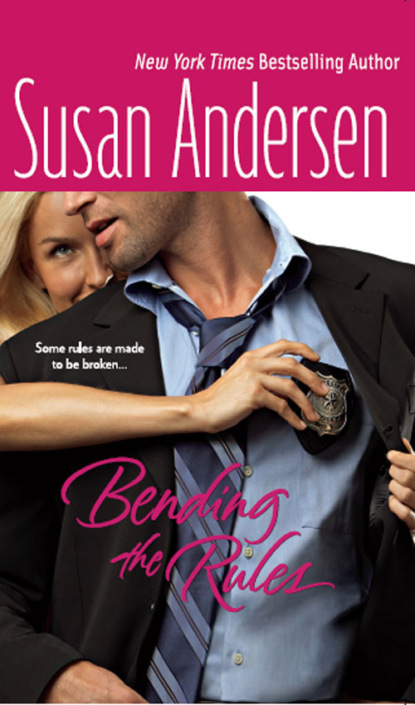

Bending the Rules

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

De Sanges nodded and looked at her for a suspended instant with those dark, uncompromising eyes. “Ms. Calloway and I have met.”

Everyone present turned to stare at her and she could almost taste the rampant curiosity and speculation. “Don’t look at me as if I were a suspect in one of his cases,” she said dryly. “You all heard about the theft we had at the Wolcott mansion a few months ago. Detective de Sanges came out to take a report when we were dissatisfied with the response we got from the first officer on the scene.”

De Sanges had been dissatisfied as well—that Ava had used one of her many contacts to have him brought in. So he hadn’t been there voluntarily, and he and Poppy had definitely gotten off on the wrong foot when she’d taken exception to what she’d perceived as his lack of concern over a break-in at the mansion that she, Jane and Ava had only recently inherited from Miss Agnes’s estate. Well, could you blame her? He had all but said he’d been yanked off a real job in order to look for their silver spoons.

Which was nothing short of ironic when you considered that only Ava had been born to money. Poppy and Jane came from working-class neighborhoods. They’d all met in the fourth grade at Country Day school—Janie attending on a scholarship and her own tuition paid by Grandma Ingles, who was herself an alumni. Even today—despite inheriting an estate that was short on cash but long on priceless collectibles and valuable real estate—Ava was the only one of them who had any discretionary income. Jane was still inventorying Miss A.’s collections and the mansion was a long way and a small fortune from being saleable, which was their ultimate goal.

Still, in the wake of Jane’s run-in with the thief, they’d learned de Sanges hadn’t just blown them off but had interviewed Jane’s coworkers at the Metropolitan Museum—had in fact spent the most time talking to Gordon Ives. And since Gordon had eventually been arrested for the crime, Poppy thought she could probably cut the detective some slack and agree he had done his job after all.

“I’d like to open the meeting for discussion,” Garret said. “I know everyone here was disturbed about how young our graffiti ‘artists’ were and you no doubt want to thrash out whether or not to press charges against them. Anyone whose business was tagged is, of course, free to do so at any time—this isn’t a case of majority rules. But we’re here to entertain all reasonable suggestions, both pro and con. So let’s get some dialogue going, people.”

No one said anything for a long, silent moment, then Jerry Harvey, whose H & A on the Ave on the corner had taken the biggest brunt of the vandalism, said, “I’d like to know who’s going to clean up the side of my shop.” He’d been the first to spot one of the kids tagging the café across from him when he’d gone to lock the front door of his funky home-decorations and art-framing shop for the night.

A few of the merchants grumbled agreement. The Ace Hardware manager pushed for pressing charges.

Poppy took a breath and quietly released it. “I have a suggestion,” she said. “I know I don’t have the same stake in the outcome of today’s meeting as the rest of you. But I was at the Hardwire when Jerry caught the kids, and frankly I was disturbed by how young they are. The officer who came in response to your call, Jerry, said this is their first brush with the law. Rather than see them thrown into the system I’d like to offer an alternate solution that directly relates to your question.”

All the merchants involved in Friday night’s excitement gave her their undivided attention. De Sanges’s eyes narrowed.

“I think it might benefit all of the businesses to give the kids something to keep them busy,” she said. “To provide them with an artistic outlet that I believe we’d find more palatable than tagging—which I freely admit I don’t get. At the same time we could teach them to take responsibility for their actions.”

“How?” Garret asked.

“First by having them clean up the tagging with a fresh coat of paint that they either have to provide themselves or work off by sweeping or handling other odd jobs for the businesses they defaced.”

“I like that so far,” Penny said thoughtfully. “Except Marlene’s place is brick, so how does that benefit her?”

“There are gels and pastes that dissolve paint from brick, and the same rules would apply—they’d supply whatever’s needed.”

Almost everyone nodded—including Jerry. But he also pinned her with a suspicious look. “So where does the ‘artistic outlet’ part come in?”

Poppy knew this was where things could go south. But it wasn’t for nothing she’d grown up with parents who got involved in causes on a near-daily basis. Not to mention the way her idea tied in to her own personal passion: bringing art to at-risk kids. Drawing a deep breath, she gave Jerry her best trust-me smile, then quietly exhaled. “I propose we keep them off the streets by letting them paint a mural on the south side of your building.”

OH, FOR CRI’SAKE. Jase leaned back in his chair and examined the woman he had privately labeled the Babe. Which, okay, wasn’t exactly a hardship since the whole package—that lithe body, exotic brown eyes and cloud of curly Nordic-pale hair—was very examinable.

He knew from experience, however, that she was a pain in the ass. And didn’t it just figure? She was a damn bleeding-heart liberal to boot.

Earlier, when he’d walked in and seen her chatting up one of the guys in this group of small-business owners, you could have knocked him off his feet with a blade of grass. He hadn’t understood why she was here, since as far as he knew she wasn’t a merchant herself. Hey, as far as he could see, she didn’t do anything useful. Of course, since he had firmly resisted the urge to run a check on her after their previous run-in, he could be wrong about that.

In any case, the president of the Merchants’Association had explained it when he’d said that Calloway was a board member.

Well, of course she was. He should have figured that out for himself after meeting her and her two rich-girl buddies last fall, when they’d used their connections with the mayor to have him yanked off a job where an old lady had been hospitalized by a mugger in order to look for their missing tea towels.

Okay, so it had turned out to be more than that—a lot more. But contrary to the Babe’s accusation that he couldn’t be bothered to do his job, he had been following the exact letter of the law when he’d told her there wasn’t much he could do for them. But he’d nevertheless been digging into Gordon Ives’s background when he got the call that a patrol officer had just arrested the man for another break-in at the Wolcott mansion—this one involving a threat against Jane Kaplinski’s life.

All of which had squat to do with today’s situation. He listened for a moment as Calloway outlined her harebrained scheme. He kept waiting for someone to shoot it down, but when he instead saw several of the merchants nodding their heads, he couldn’t take it any longer. “You’re kidding me, right?”

Slowly, she turned her head to look at him. “Excuse me?”

“I figure this has to be a joke, because you can’t possibly be serious. They broke the law. You want to reward them for that?”

Her eyes flashed fire, giving him an abrupt flash of his own—of déjà vu. Because he was no stranger to that phenomenon—her eyes had done the exact same thing when she’d leaned over him in the chair where he’d sat in the mansion parlor, taking their report last year. Serious chemistry had flared to life between them, but he was damned if he planned to fall prey to that again.

Maybe she was thinking along the same lines, because she didn’t climb over the table to get in his face the way she had last time. Instead, she said coolly, “No, Detective, I am not kidding. I’m pretty darn serious, in fact. These aren’t hardened criminals we’re talking about—they’re children, the oldest barely seventeen.”

“Yeah, they start ‘em young these days,” he agreed.

“It’s not as if they committed a violent crime—they didn’t mug an old lady or attempt to rob someone at gunpoint at the ATM machine.” Her eyes narrowed. “Or commit a burglary of any kind,” she said with slow thoughtfulness, and he could almost smell the circuits burning as she followed that thought to its logical conclusion.

“They didn’t commit a burglary,” she repeated, gazing around the table at the other occupants. Then she looked him dead in the eye. “So why are you sitting on this panel, again?”

Excellent question. When Greer had offered to put his name in for the mayor’s task force he’d given his lieutenant an immediate and firm “Thanks, but no thanks.” Then, like an idiot, he’d let Murphy—the old cop who had stepped in years ago to take him in hand before the de Sanges genes could screw him up entirely—talk him into changing his mind. Murph had insisted that if Jase wanted to wear those lieutenant bars himself someday—which he did—he needed to start making his name known to the powers that be. And a good way to do that was to be part of these task forces—even if this particular one was more about election-year public relations than the war on crime.

So here he sat, proving once again that no good deed goes unpunished.

Not letting his thoughts show, however, he merely met her suspicious gaze with the cool straightforwardness of his own, evincing none of his reluctance to be part of this dog-and-pony show. “Because this is how we so often see it begin. Baby street punks grow up to be full-fledged street punks. Today it’s tagging or stealing some other kid’s lunch money at school—if they even bother to show up at school, that is.”

“So perhaps we should make that a condition of my proposal. No school, no participation in the art project.”

Slick, he thought with unwilling admiration, but said as if she hadn’t spoken, “Tomorrow it’s mugging some little old lady in the parking lot at Northgate.” Pulling his gaze away from the Babe’s, he included the entire table of merchants in his regard. “Or right here in your own community.”

Okay, so maybe he was overstating the case a little, adding a dash of drama to get his point across. He was so tired, however, of watching punks bend the rules and not merely not be called on it but get special treatment for their efforts as well. That was just bogus. And it happened too often.

Still, he was surprised at the impact his words had. The business owners’ voices started buzzing around the table as they discussed the repercussions of allowing hardened criminals into their neighborhood business sector.

Wait a minute. His brows snapped together. Had he given them that impression, that the boys in this case were hardened criminals? Jesus, de Sanges, the Babe is right about that much at least. They’re kids who committed their first offense.

As if she could read his thoughts, she repeated to the group around the table, “They’re kids, you guys. Barely past puberty kids without a single police record between them. Please keep that in mind.”

“I’m keeping in mind that Detective de Sanges said that’s how all street punks start,” the man who had been introduced as the manager of Ace Hardware said.

“I didn’t say all,” Jase disagreed. “But I do see enough juvenile offenders to make it one factor to consider.”

“Surely,” Poppy insisted, “most of those that you see are involved in an actual robbery or mugging.”

“True. Most—but not all—are.”

“Does anyone else have an argument, either pro or con, that they’d like to throw out for discussion?” Garret asked.

“I’d just like to reiterate that these are kids who have never been in trouble with the law,” Poppy said quietly. “I’m not saying let them skip out of their obligations. Just, please, let’s not be the ones to give them their first police record.”

“Anyone else?” Garret asked. Getting no response, he said, “Does anyone plan on pressing charges?”

When no one said anything to that, either, he said, “I’ll take that as a provisional no.” He turned to Poppy. “Can I hear an official proposal?”

She straightened her shoulders, which had temporarily slumped. Shook back hair so thick and curly the entire mass quivered. “I propose we teach the three boys who tagged your businesses a sense of accountability by making them cover or remove the vandalized areas with paint and/or paint dissolvers that they provide at their own expense. I further propose—”

“Let’s do this one motion at a time,” Garret interrupted. He looked around the table. “Would anyone like to second that?”