По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

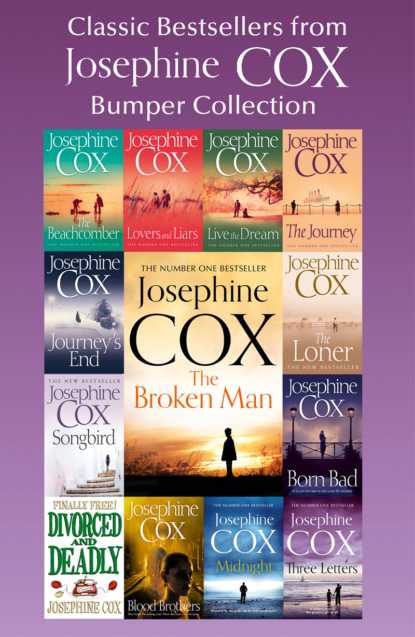

Classic Bestsellers from Josephine Cox: Bumper Collection

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

With that he got up from his seat and struggled drunkenly to the bar.

John followed him with a curious gaze. Poor devil, he looked like he’d been through the mill. Yet there was something familiar about him … He shook his head. The strange feeling lingered, and then Archie was talking again, drawing his thoughts back to the conversation between them.

‘So, you see, shipmate, I ain’t got much choice, have I?’

John nodded in agreement. ‘So, what will you do with yourself?’

‘Oh, I dare say I’ll sleep well at night, and wander about the quayside during the daylight hours. I was born and bred in Liverpool, so I know most o’ these seafaring folks. I expect I’ll find a bit o’ work here and there.’

At that moment, raised voices were heard from the bar, and Archie said with a grin, ‘It seems our friend’s had more than enough ale, and now the landlord wants shut of him.’

Archie was right. With a good measure of ale inside him, the fellow who’d been sitting next to them was loudly explaining to the landlord, ‘I’ve money to pay for it. Look!’ Emptying a shower of farthings, ha’pennies and threepenny bits all over the counter, he showed he had the wherewithal for a couple more pints at least.

The landlord pushed the coins back irritably. ‘Put your money away. Look at yourself, man! You can hardly stand up!’

When the man leaned over the bar, the landlord thought he was in for a spell of trouble, so he was taken aback when suddenly the sad-eyed fellow asked him, his voice breaking with emotion, ‘Would you take me for a coward?’

‘Maybe.’ The landlord could see he was at his wits’ end. ‘Maybe not. We’re all cowards sometimes, one way or another.’

The man looked him straight in the eye. ‘Well, I’m the worst kind of all.’

‘Oh, aye? An’ what kind is that then?’

The man smiled back, the sorriest smile the landlord had seen in all his years behind that bar. ‘What kind would you call a man who runs out on his family?’

The landlord thought of his own shortcomings and gave a sheepish grin. ‘I reckon we’ve all done that in our time.’

The younger man wagged a finger. ‘Ah, but you see, I ran out on the finest daughter in the world, and her mammy too … the best wife a man could have.’ He gave a soul-destroying sigh. ‘My poor Aggie, God forgive me! I left her with my poorly father, and debts she could never pay in a hundred years. So, tell me! What kind of coward does that make me, eh?’

The landlord’s answer was to draw him a jug of ale and, planting it in front of him, he instructed, ‘This is your last one in this establishment. So, come on! Sup up, and be on your way. I’ve enough of my own troubles to worry about yours!’ But he said it in a kind way, and refused any payment.

The sad-eyed man nodded. ‘Thank you, sir.’ He took a sip, and then another and, as always, the more he sank into his ale, the further away his troubles receded.

Archie too, was sipping his ale, lost in thought, when suddenly John’s voice intruded. ‘Have you got a place to stay?’

‘Not yet, but I’ll get fixed up soon enough.’ Archie tapped his jacket pocket. ‘I’ve enough to pay for a room and feed myself for a few weeks. Meantime, as I said, I’ll soon be running errands and suchlike to keep the roof over my head.’ He gave a sort of smile. ‘I’ll need to earn a wage, so’s I can come and sit in here and watch the world go by.’

Underneath the little man’s bravado, there was a sense of fear, and John was concerned about him. ‘I’ll stay with you if you like, until you’re fixed up with a room.’

Archie was horrified. ‘You will not!’ Wagging a finger he argued, ‘You’ll finish your drink, then you’ll get yourself off to that lovely girl of yours.’ Realising there were those nearby who were listening to their conversation, he lowered his voice to a whisper. ‘I’m grateful for your concern, but I’ve been on my own since I was a lad in short breeches. I’m more than capable of looking after meself.’

John was mortified to have offended him. ‘I’m sorry,’ he apologised, ‘only I thought you might need a friend.’

Archie thanked him again, but, ‘It’s Emily that needs you now,’ he said kindly.

John’s face lit up. ‘Oh Archie! I can’t wait till I see her again!’

‘Well, o’ course you can’t. What! She’s all you’ve talked about these past two years. “Emily this” … “Emily that”. Day and night, until I feel I know her as well as you do.’

Something was still worrying John. ‘Why didn’t she reply to my letters, Archie?’ he burst out. ‘I wrote all those letters and every time we got to a port, I took them to be posted home. But I never got any reply.’

The old man knew this had been on John’s mind for some time, and yet again, he tried to explain it away the best he could. ‘How many letters did you write to your Auntie Lizzie?’

John did a mental calculation. ‘One a month … same number as I wrote to Emily.’

‘And how many replies got through to you?’

Reaching into his pocket, John took out a crumpled envelope. ‘Just the one.’ He had read that letter time and again, until the folds were almost worn through, and the words hardly visible any more.

Archie waved a crooked finger. ‘There you go then! It’s just like I told you. Some of them foreign post offices take your money and don’t give a bugger for your letter. Like as not they’ll tear it up and drop it into the ocean. It’s often the truth that a letter never gets to its destination. And even if it’s put on a ship to be brought home, who’s to say it ever gets to the right address? What! I’ve known men send hundreds and never a one reached home. It happens, that’s all. And there isn’t a damned thing you can do about it.’

‘I expect you’re right, Archie.’ Taking a deep sigh, John blew it out with the words, ‘I hope that’s all it is. I hope she hasn’t found somebody else to take my place.’

Archie wouldn’t hear of it, and besides, ‘Didn’t you say your aunt told you in that there letter, how soon after you’d gone, Emily was so lonely for you, she wouldn’t hardly leave the farm?’

John recalled every word, but, ‘This was got to me in the first month of me being away. I’ve not heard a word since.’

‘Aw, stop your worrying.’ Archie took a swig of his ale and, wiping the froth from his mouth, he promised John, ‘She’ll be there, waiting for you. You needn’t worry about that.’

Encouraged by his pal’s assurances, John put the worries to the back of his mind. ‘I’m going home, matey,’ he said. ‘I’m going home to my Emily, and I’m never leaving her side again.’

Raising his jug of ale, Archie bade John do the same. He gave a toast. ‘To Emily, and yourself. May you live long and be happy together.’

John had another toast. ‘To yourself, Archie. That you find contentment in your new life back ashore.’

They drank to that, and soon Archie took his leave. ‘Got to see a man about a room, then it’s off to find work of a kind,’ he said. ‘You take care of yourself, son. You’ve already given me your aunt’s address, so as soon as I’m settled, I’ll write to you.’ A big grin lifted his features. ‘This letter won’t have oceans to cross, so you should get it all right.’

John watched him leave, and when the loneliness flooded over him, he strode across the room to the bar, where he took instructions from the landlord, paid his way, and was soon shown to the back parlour, where his ‘lukewarm’ bath was ready and waiting.

Some time later, he emerged refreshed, smartly dressed in his new clothes, and ready for his journey. With a lighter heart, he bade the landlord goodbye and headed for the door.

The sooner he was out of the Sailor’s Rest and on his way home, the better.

Chapter 6 (#ulink_fef19a23-4c6d-5c5a-b318-02b894502e4b)

‘IT’S NO USE you arguing with me,’ Thomas Isaac insisted. ‘I haven’t been out of this room in weeks, and now I’m feeling stronger, I intend being downstairs to see that little lass blow out her birthday candles.’ His homely old face withered into a crooked smile. ‘Two year old – I can’t believe it!’

Aggie sighed. ‘That’s how quickly life passes us by,’ she said philosophically. ‘She were born March 1903, now it’s suddenly 1905. Two year old today … twelve year old tomorrow. Afore you know it, our Cathleen’ll be a woman with a husband and childer of her own, Lord help us!’

The old fella lapsed into a mood of nostalgia. ‘I just hope the same Good Lord lets me live to see the day.’

Aggie rolled her eyes to the ceiling. ‘Aw, give over, Dad. You’ll not get round me that way. I know you too well to let you bamboozle me into feeling sorry for you.’ She gave him a knowing wink. ‘So you might as well stop trying.’

He looked shocked. ‘I don’t know what yer talking about, woman!’

‘Oh, yes you do,’ Aggie retaliated. ‘You’re badgering me to get you downstairs, even after the doctor has given strict instructions that after this last chest cold o’ yourn, you’re to stay in bed, well wrapped up and with a roaring fire in the grate.’ She was pleased to see that the fire had got a good hold, with the flames already leaping up the chimney. Even in March, when the sun began to struggle through, these farmhouse bedrooms were awfully cold.

‘You make me out to be a tyrant.’ The old man’s querulous voice brought her attention back to him.