По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

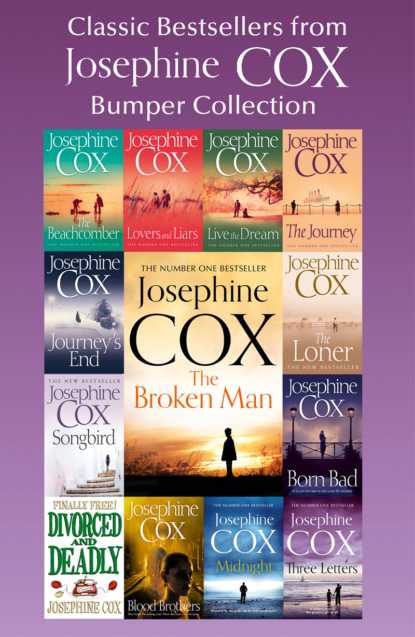

Classic Bestsellers from Josephine Cox: Bumper Collection

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

In fact, they had little choice, because now Emily was back, with a tray containing a dish of cold bread pudding and two mugs of tea. ‘I hope you are ready for this, Gramps,’ she said, her quick smile lighting up the room. ‘Mam’s given you a helping and a half, although she says it’s a funny sort of a breakfast.’ She set the tray down before making good her escape. ‘Mam’s baking and Cathleen’s asleep. I’ve got a pile of washing bubbling in the copper, so I’d best be off.’ With that she was across the room and out the door.

‘I’ll pop in and see you before I leave!’ Danny called out, and from somewhere down the stairs came a muffled reply.

‘Ask her while she’s up to her armpits in soapsuds,’ the old man suggested with a wink.

‘You won’t give up, will you?’ Danny laughed. And neither will I, he thought.

Because, as sure as day followed night, he would keep asking Emily to be his wife, until in the end she had to agree.

Ten minutes later, feeling all the better for this break, Danny called in on Emily as he had promised.

The girl was not up to her armpits in soapsuds, as the old man had predicted. Instead she had already lifted the clothes out of the copper boiler with the wooden tongs and was in the middle of rinsing them in the big sink. The small stone outhouse was thick with steam erupting from the copper, and Emily’s face was bright pink from the heat.

‘Here, let me do that!’ Dodging the many clothes-lines stretched criss-cross from one end of the outhouse to the other, Danny made his way through to her.

As Emily fought to wring out a huge bedsheet, he took hold of it and without effort fed it through the mangle and then folded it and draped it over the line. He looked at the growing mountain of damp clothes on the wooden drainer. ‘Do you want me to stay and help?’ he asked hopefully.

She thanked him, but, ‘You get off now and finish your rounds,’ she suggested graciously. ‘I’ve almost done here.’

He hid his disappointment. ‘These bedsheets weigh a ton when they’re wet,’ he remarked.

Knowing he would linger all day if she encouraged him, Emily was adamant. ‘I’m used to it,’ she said. ‘If I had help, I’d lose the routine and it would only take longer in the end, if you know what I mean?’

Grudgingly, but with a ready grin, he bade her goodbye. ‘I’ll see you tomorrow then?’

‘I’ll look forward to it,’ she said. And that was the truth.

Coming to the door of the outhouse, she waved him away. You’re persistent, I’ll give you that, she thought kindly. Somewhere, there’s a woman who would give her right arm to be your wife. I’m sorry, Danny, but it’s not me. Without even being aware that she’d been thinking it, the words fell out. ‘More’s the pity.’

A little surprised and bewildered, she made her way back into the outhouse, where she threw herself into the task in hand. It had been an odd thing to say, she mused. As though to shut it out, she filled her mind with thoughts of John. And, as always, the love for him was overwhelming.

An hour later, Emily had finished. With all the washing hanging limp and bedraggled over the lines, she made her way to the shed where she collected an armful of kindling.

That done she returned to the outhouse, where she made a bed of newspaper in the fire-grate; on top of that she laid the wood in a kind of pyramid. Next, taking a match from the mantelpiece, she set light to the paper.

When that was all flaring and crackling, she took the smallest pieces of coal from the bucket and built another pyramid over the first. On her knees, she stretched a sheet of paper over the fireplace to encourage the flames, then watched and waited until the whole lot was burning and glowing; the heat tickling her face and making her warm.

‘That’ll soon dry it out,’ she murmured, clambering to her knees.

Replacing the screen in front of the fire, she made her way out, carefully dodging and ducking the damp clothes as she went.

Inside the scullery, Aggie had a brew of tea waiting for her. ‘All done, are you, lass?’ Taking off her long goffered apron and wearily lowering herself into the fireside-chair, Aggie laid back and closed her eyes. ‘Me back’s fit to break in two,’ she groaned. ‘I swear, there’s enough work in this farmhouse to keep an army on their toes! I’ll have to get the dinner going in an hour or so. It’ll be a simple meal, seeing as it’s Christmas Day tomorrow. I’ve got some cold beef and pickled onion with mashed potato, and tapioca wi’ bottled gooseberries for afters. What d’you reckon to that, lass?’

Settling in the chair opposite, her tea clutched in her fist, Emily said, ‘It sounds lovely, Mam. Cathleen still asleep, is she?’

‘The bairn hasn’t moved a muscle since you went out,’ Aggie answered, opening one eye. ‘Looks like Danny’s worn her out.’

Emily laughed. ‘He’s worn me out an’ all.’

Detecting the underlying seriousness of Emily’s remark, Aggie asked pointedly, ‘Been on at you to wed him again, has he?’

‘He means well,’ Emily said. ‘And I dare say he would move heaven and earth to make me and Cathleen happy …’

‘But?’

Emily knew all the old arguments. ‘But what?’

Aggie answered exactly the way Emily had expected. ‘But your heart’s out there with John Hanley. I expect that’s what you told Danny?’

‘Yes, but he already knows it.’

‘I see.’ As ever, Aggie read the situation well. She also knew that in the end, someone was bound to get hurt.

For a few minutes, the two women sat lost in thought, quietly listening to the fire roaring. The tassels on the chenille runner that covered the mantelshelf danced in the heat, and light reflected off the glass dome of the clock and the framed picture of Queen Victoria that Clare Ramsden had bought on a visit to Blackpool in 1885.

After a while, Aggie asked, ‘How long are you prepared to wait, lass?’

Emily had been so deep in thought she hadn’t heard the full question. ‘Wait for what?’

‘For John to come home?’

‘I wish I knew, Mam.’ Emily had asked herself that same question time and again, and still she wasn’t sure. ‘As long as it takes, I suppose.’

‘And how long is that?’ Aggie was concerned about her daughter’s wellbeing. She had seen her growing lonelier and quieter, and it cut her to the quick. ‘Are you thinking weeks, months …’ her eyebrows went up at the prospect. ‘Or do you mean to wait for years – is that it?’ Part of her acknowledged her own pain at Michael’s abandonment. She and Emily were made of the same strong clay: they could manage without their men, but that didn’t mean it was easy. And Emily was still young – she should be wed to someone who loved her and who could give her another bairn as company for Cathleen.

‘I don’t know,’ Emily admitted. ‘All I do know is that I love him with all my heart. When John left, he said he’d be back. I promised him I’d wait. And I will keep that promise.’

Aggie pressed the point. ‘And will you wait until little Cathleen is two or three? Or will you wait until she starts playing with other children from the village – children who know what it’s like to have a daddy at home. And when she starts asking where her daddy is, have you got an answer ready, my girl? Tell me that.’

Now as Emily glanced up her eyes were moist with tears. ‘I know what you’re trying to say, Mam, and I understand,’ she said brokenly. ‘I’ve been thinking of little Cathleen too, and the older she gets the more I worry. But I can’t marry Danny. As much as I like and respect him, and as much as I know he would look after us, I can’t bring myself to marry him, not when I still love John. I keep hoping that John is safe and well: I can’t stop thinking about him, Mam. He’s on my mind the whole time, night and day.’

Wiping a tear, she finished, ‘Besides, Danny deserves better than that.’

Aggie said nothing. Instead she sipped at her tea and wondered what would become of them all.

Emily was grateful for the lull in the conversation. Only time would tell whether John would return, and if he didn’t do so soon, she would have to decide what to do. But it wouldn’t be easy, she knew that.

The child’s waking cries shook them out of their reverie. But when the infant’s cries lapsed into a string of happy gobbledy-gook, Emily lingered a moment. ‘I’ve a good mind to go and see Lizzie,’ she revealed. ‘You never know. She might have word of John.’

Aggie warned her, ‘Well, I hope the old bugger makes you more welcome than she did last time!’ she declared. ‘What! She wound you up so much you wouldn’t speak for a whole hour.’

Emily remembered. ‘She was a bit … difficult, that’s all.’

‘Hmh!’ Aggie sat up. ‘Cantankerous, more like! Heaven knows what’s the matter wi’ her. Ever since her John went away she’s been as sour as a rhubarb pie without a morsel o’ sugar.’

‘She’s getting old, poor thing.’ Emily had a soft spot for Lizzie. ‘She suffers a lot from pain in her joints.’

Aggie had little sympathy. ‘She’s too proud – won’t let anybody help her. You heard Danny say how he found her climbing a ladder to mend that hole in the thatch the other week. When he offered to do it for her, she told him to sod off – said that she wasn’t yet ready for the knacker’s yard!’ She wagged a finger. ‘If you ask me, you’ll do well to steer clear of the old battle-axe.’