По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

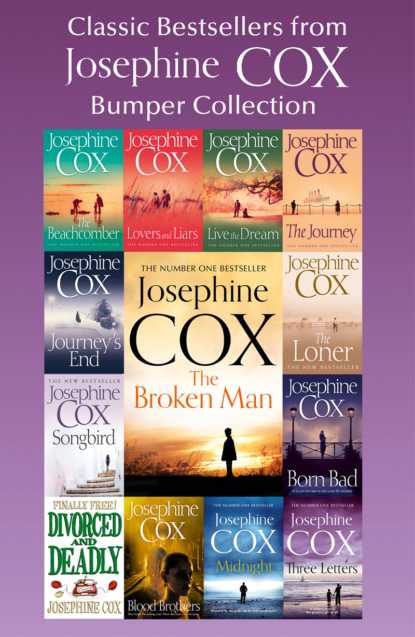

Classic Bestsellers from Josephine Cox: Bumper Collection

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

It was almost pitch dark when he got back to the cottage. ‘You had me worried.’ Lizzie was waiting anxiously for him. ‘Are you all right, son?’

‘I’m fine,’ he lied, ‘but I shouldn’t have worried you like that. I’m sorry. I just lost track of time.’

When she saw his fist, bloodied and torn, she insisted on tending it, and while he sat she talked, about everything but Emily. ‘When me old bones let me, I intend digging over that hard area at the bottom of the garden,’ she declared. ‘Y’see, I’ve a mind to extend the vegetable patch.’

John didn’t comment. It was just small talk. What good was small talk, when his whole life had just fallen apart around him? But he smiled and nodded, and Lizzie seemed content enough at that.

After a while, when the hand was washed and treated and she had out-talked herself, Lizzie gave a sigh. ‘I’m off to my bed now,’ she said. ‘I reckon you should do the same, son.’

He looked so tired, she thought. ‘In the morning, I’ll wake you to the smell of crispy bacon curling in the pan, and some of my fresh-laid eggs – oh, and did you know I bought another two chickens? O’ course, I can’t eat all the eggs meself, but I earn an extra bob or two selling them at market.’ She chuckled. ‘I’ve a good life here, in Salmesbury,’ she said. ‘To tell you the truth, son, there’s nowhere else in the world I want to be.’

With his arm round her shoulders, John kissed her good night. ‘You’re a good woman, and I love you,’ he said fondly. ‘If there’s ever anything you need, I’ll always be there for you.’

‘I know that,’ she said. ‘And I hope I’ll always be there for you.’

That night, when Lizzie was fast asleep in her bed, John went outside and, taking the spade and fork from the lean-to shed, he rolled up his sleeves and set about digging over the small patch of ground at the foot of Lizzie’s garden. He soon got into the rhythm of digging, then breaking up and forking over the soil, chucking weeds onto the compost heap.

When that was done and the last spadeful of earth had been turned over, he stood back and surveyed it. Satisfied, he returned to the house and after washing off the dirt and tidying himself up, he dug in his kitbag for paper and pencil.

A few moments later, seated at the table, with the glow of lamplight illuminating the page, he began the first of his letters:

Dearest Lizzie,

You’ve been the best mother anyone could have. It hurts me to leave you like this, but I have a feeling you will understand. You have always understood me, better than anyone.

The news of Emily has shaken me to my roots, as you must know. I came back here to marry her, but sadly, it wasn’t to be.

I’m leaving you this money. It is part of the sum I had put aside for our wedding, and to resolve other matters which would make life easier for Emily and her family. But she has made her choice, and there is nothing I can do about that.

Use the money wisely. Don’t overwork yourself, and stay well. I know now you will never leave this place, and who could blame you? If all had been well with me and Emily, I too would never want to live anywhere else.

I’m enclosing a letter for Emily. It’s just to wish her well, that’s all. I ask that you might please take it to her. But you must not let her know that I was here, or that I have learned she has a husband and child. I ask you that for a reason.

All my love. I will keep in touch, so please don’t worry.

Your loving nephew,

John

Because of its content, his letter to Emily was shorter. Rather than make her feel guilty, he took the blame on himself.

When it was written, he went to the dresser-drawer, where he knew Lizzie kept envelopes and such. From here, he took one small envelope, folded Emily’s letter inside Lizzie’s, and enclosed them both in the envelope. He then propped it in front of the mantelpiece-clock, laid the wad of money beside it, and with one last, fond glance upwards, towards Lizzie’s bedroom, he took his kitbag and left.

All his instincts wanted to take him by way of Potts End Farm. He knew how Emily would already be out of her bed and working at some task or other. He had visions of going to her and begging her to leave the husband she had taken and come away with him. It was a shameful thing, he thought, and the idea was soon thrust away. ‘She isn’t yours any more,’ he told himself, his gaze wandering towards the spinney.

All the same, leaving her behind was the hardest thing he had ever done.

In the morning when Lizzie woke, she knew instinctively that he had gone. ‘John?’ she called down the stairs. There was no answer, so she called louder. ‘JOHN!’

Throwing a robe over her nightdress, she hurried downstairs. The minute she entered the room, she saw the letter. Oh, dear Lord. He’d gone! Her heart fell. But he’d be back, she knew he would. Though whether that would be a good thing or a bad one, she couldn’t tell.

The wad of money shocked her. By! What did he have to go and do that for? She quickly read the note and was enlightened. ‘I’ll not spend it wisely,’ she said aloud, ‘’cause I’ll not spend it at all. One o’ these fine days, son, you’ll be looking to wed some young woman or other, and when that day comes, the money will be here waiting for you.’

She thought of her situation and of how she had always managed to earn a living selling her produce and pies at the market. A proud woman, she had never taken a helping hand from anyone, and she wasn’t about to start now, even if that hand belonged to the person she loved most in the whole world.

Crossing to the kitchen range, she took a loose stone from the wall to reveal a clever hidey-hole. From here she drew out a small square baccy tin. Inside was a small hand-stitched drawstring bag containing a number of guineas.

She counted the coins for the umpteenth time. Five whole guineas! Not bad for an old woman, was it? Mind, it had taken hard work and thrift to build up such a cache over the years. The wad of notes was far more money than she could ever save in her lifetime, and she instinctively glanced about before placing the wad into the drawstring bag. She then returned the baccy tin to the hole in the wall, replaced the stone and pushed a saucepan up against it.

Later that afternoon, Lizzie put on her best shawl and hat, and made her way across the fields and down through the spinney to Potts End Farm. Just as she had expected, Emily was to be found in the wash-house. ‘I’ve heard from John,’ Lizzie said abruptly, standing in the door. ‘He sent this for you.’

Holding out the letter, she was made to feel guilty when Emily ran across the room, her face alight. ‘Oh, Lizzie!’ Wiping her hands on her apron, she took the letter in hands that had begun to shake. ‘What does he say? Is he coming home? Is he?’ The words tumbled out as she unfolded the letter.

But when the young woman read her lover’s message, her tears of joy turned to sobs of despair:

Dear Emily,

Forgive me for what I’m about to tell you. I won’t be coming home, or getting wed as we planned.

I never meant for it to happen, but I’ve found a new love.

I had to write to you straight away, for I don’t want you wasting your life in waiting for me.

I hope you’ll find someone who will love and cherish you as you deserve; because although it wasn’t meant for you and me to be together, you are a very special and lovely person, Emily.

Please forgive me,

John

Now, as Emily looked up, her face crumpled with shock and pain, Lizzie was stricken with a terrible remorse. ‘Aw, lass.’ Going over to the girl, she put a comforting arm round her heaving shoulders. ‘I’m so sorry.’ And she was. But she couldn’t confess why; not to Emily nor to anyone else.

Even now, she could not deny in her own heart how she truly believed the parting would be best for both of them in the long run.

She comforted Emily as best she could, but it was of little consolation to the girl, who felt as though her life had come to an end. ‘How can I live without ever seeing him again?’ she asked brokenly. ‘How can I be without him, when I love him with all my heart?’

Unable to provide the answers, Lizzie left some short time later. As she climbed the brow of the hill, she thought she could still hear the sound of Emily’s sobbing, carried on the breeze.

‘God help me!’ Lizzie murmured. But it was for the best that Emily should wed the father of her child. For the best, that John was not fettered by another man’s responsibility.

And not forgetting the child itself, wasn’t it for the best that Cathleen should be brought up in the family security of her own father and mother?

Suddenly, when the breeze became wild, cutting across the hills like a banshee, Lizzie tightened her shawl and quickened her steps.

‘I did right!’ she told the wind. ‘I’m sorry for the pain I caused, but it was the right thing to do.’ A woman of high principles, Lizzie believed that mistakes had to be paid for, and that was Emily’s punishment.

As for John, he had done nothing wrong as far as she could see, so it was only right that he should make a new life without encumbrances not of his making.

As far as Lizzie was concerned, that was how she saw it, and if there was any blame to be apportioned in this deceitful business, it lay fair and square with young Emily.