По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

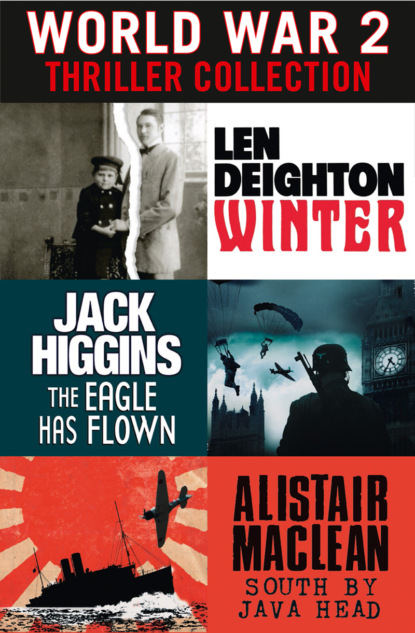

World War 2 Thriller Collection: Winter, The Eagle Has Flown, South by Java Head

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

They watched the airship come out on the surface of the lake, and then there was an interminable delay while the royal party inspected the airship, and another while it was given the final adjustments for the flight. After the Prince and Princess of Fürstenberg were safely aboard, the ballast was offloaded piece by piece, until the moment came when the great silver machine shuddered and floated free.

The roar of the engines echoed across the cold still water of the Bodensee, and then the nose tilted up and the airship climbed slowly into the grey sky and, rolling slightly as it went, headed down the lake. The airship’s silver fabric was shining in the pale sunlight as it came steadily back to where the shore was black with onlookers. There were more loud, uncoordinated cheers as it passed over the boat from which the Kaiser and his entourage watched.

But it was after the landing of LZ3 that the boys were proudest of their father. For Harald Winter was invited to take his two sons out to the floating shed to watch Kaiser Wilhelm making his speech.

Every available inch of space was used. Illustrious generals, spiked helmets on their heads and chests crammed with medals, and admirals with high, stiff collars and arms garlanded with gold, were all crowded shoulder to shoulder. Standing behind von Zeppelin – the seventy-one-year-old ex-cavalry officer whose single-minded endeavour was today celebrated – they saw Dr Hugo Eckener, whose conversion to the zeppelin cause had made him even more zealous than his master. Next came Dürr, the engineer, Winter with the two children, and then senior design staff and an official from the engine factory.

‘In my name,’ began the Kaiser suddenly, his voice unexpectedly shrill, ‘and in the name of our entire German people, I heartily congratulate Your Excellency on this magnificent work which you have so wonderfully displayed before me today. Our Fatherland can be proud to possess such a son – the greatest German of the twentieth century – who through his invention has brought us to a new point in the development of the human race.’ At this, one or two of the generals and admirals nodded. One of the design staff edged aside to give little Pauli a better view.

The Kaiser looked round his audience, drew himself up into an even more erect posture, and continued: ‘It is not too much to say that we have today lived through one of the greatest moments in the evolution of human culture. I thank God, with all Germans, that He has considered our people worthy to name you as one of us. Might it be permitted to us all, as it has been to you, to be able to say with pride in the evening of our life, that we had been successful in serving our dear Fatherland so fruitfully. As a token of my admiring recognition, which certainly all your guests gathered here share with the entire German people, I bestow upon you herewith my high Order of the Black Eagle.’

Count Zeppelin stepped one pace forward. Over his head the Kaiser put the sash, and then embraced him three times and called, ‘His Excellency Count Zeppelin, the conqueror of the air – hurrah!’

From the crowd in the distance, cheers could be heard. For Winter and his two sons it was a day they would never forget.

It was already getting dark by the time Winter and the boys got back to the hotel in Friedrichshafen. Nanny was sent to have dinner alone in the restaurant so that the boys could have theirs served in the sitting room of their suite. Harald Winter was excited by the events of the day, and at times like this he liked to have a few extra moments with his sons.

A solicitous waiter in a white jacket brought the meal and served it to the children course by course. There was turtle soup and breaded schnitzels with rösti potatoes, which the Swiss, across the lake, did so perfectly. When no one was looking, Peter took forkfuls of Pauli’s cabbage – Pauli hated cabbage – so that he wouldn’t get into trouble for leaving it on his plate. And after that the waiter flamed crêpes for them. It was the first time that their father had permitted them to have a dish containing alcohol and, despite the strong flavour, the boys devoured their pancakes with great joy, slowing their eating to prolong this happy day forever.

After Nanny had taken the boys off to bed, Harald had a chance to express his happiness to his wife. They were in the bedroom; Veronica’s maid had gone. Harry was fully dressed in his evening clothes and his wife was making a final selection of jewellery. She had already put three different diamond brooches on her low-cut ballgown and rejected each. She was wearing a wonderful new Poiret dress from Paris, a simple tubular design with a high waist. She knew the new Paris look would create a sensation at the ball tonight. But on such a neoclassical design the jewellery would be all-important. She didn’t want to get it wrong. ‘What do you think, Harry?’ She turned away from the mirror enough for him to see her hold the diamond-studded gold rose against her.

‘You’re very beautiful, my darling,’ he told her.

‘I’m thirty-four, Harry, and I feel every year of it. My shoes hurt already, and the evening has not even started.’

‘Change them,’ said Harry.

‘The pink silk shoes would look absurd,’ she said.

He smiled. That was the way women were: the pink shoes looked absurd, the white ones hurt; there was really no answer. Perhaps women liked always to have some problem or other: perhaps it was the way they accounted for their disappointments. ‘Did you see His Majesty?’

‘I got so cold, Harry. I just waited until the airship lifted away. Then I came back for a hot bath.’

‘The boys saw him. He looked magnificent. He’s a great man.’

‘I’ll just have to slip them off at dinner.’

‘The LZ3 is to be delivered to the army right away. And as soon as the LZ5 is completed – and has done a twenty-four-hour endurance flight – they want that, too.’

‘I know. You told me. It’s wonderful.’

‘You realize what it means, don’t you?’

‘No,’ she said vaguely. She’d heard it all before. She wasn’t listening to him; she was looking at her shoes.

‘It means we’ll be rich, darling.’

‘We’re already rich, Harry.’

‘I mean really rich: tens of millions …perhaps a hundred million before I’m finished.’ He sat down, reaching behind him to flip his coat tails high in the air like a blackbird alighting. You could tell a lot about a man by the way he sat down, she decided. Her father always lifted his coat tails aside carefully, making sure they’d not be creased.

‘We’re happy, Harry. That’s the important thing.’

‘Dollars, I’m talking about, not Reichsmarks.’

‘What does it matter, Harry? We’re happy, aren’t we?’ She looked up at him. Somewhere deep inside her there arose a desperate hope that he would embrace her and tell her that he would give up his other women. But she knew he would not do that. He needed the women, the way he needed the money. He had to be reassured, just as little Pauli needed so much reassurance all the time.

‘It doesn’t matter to you,’ he said, and she was surprised at the bitterness in his voice. He was like that; his mood could change suddenly for no accountable reason. ‘You were born into wealth. You have your own bank account and your father’s allowance every year. But now I’ll have as much money as he’s got. I won’t have to kowtow to him all the time.’

‘I haven’t noticed you displaying servile deference to Papa,’ she said. She gave him all her attention.

He ignored her remark. ‘The army will buy more and more airships, and the navy will buy them, too. I had a word with the admiral today. They’re already planning where the bases should be. Nordholz in Schleswig-Holstein will be the biggest one; then others nearby. Revolving sheds built on turntables – the North Sea is too rough for floating the hangars.’

‘Schleswig-Holstein? Why would they want them so far north? The weather there is not suited to airships. You said they’d need calm weather today.’

‘Use your brains, Veronica. Germany has the only practical flying machine in the world. The experimental little contraptions that the Wright brothers have made can scarcely lift the weight of a man. What use would those things be for bombing?’

‘Bombing? Bombing England?’

‘This has been Count Zeppelin’s idea right from the start. I thought everyone knew that. He conceived these huge rigid airships as a war-winning weapon.’

‘How ghastly!’

‘It’s how progress comes. Leonardo da Vinci developed his great ideas only to help his masters fight wars.’

‘But bombing England, Harry? For God’s sake. What are you saying?’

‘Don’t get excited, Veronica. I wish I hadn’t started talking about it.’

‘War? War with England? But, Harry it is no time at all since the King of England went to Berlin. The children saw them both going through Pariser Platz in the state coach. The Kaiser is King Edward’s nephew. It’s unthinkable. It’s madness!’ This came in a gabble. It was as if she thought that she had only her husband to persuade and everything would be all right.

It was not an appropriate time to remind her that Kaiser Wilhelm made no secret of his hatred for his uncle the English King. Only the previous year, Winter had been one of three hundred dinner guests to whom the Kaiser had confided that King Edward was ‘a Satan’. But his wife needed assurance, so he went to her and put his arms tightly round her. By God, she was beautiful. Even at thirty-four she outshone some of the younger ones he bedded. He hated to see her distressed. ‘There will be no war, my darling. I guarantee that. England will see sense. When the time comes, England will see sense. The English are a nation of compromisers.’

‘I pray to God you’re right.’

‘They say the mustard manufacturers get rich from the dabs of mustard people leave on their plates. And we’ll get rich in the same way, darling. From selling the soldiers weapons they’ll never use.’

1910

The end of Valhalla

Both boys liked to visit Omi. Harald Winter’s widowed mother, Effi, lived in a comfortable little house on the coast, near Travemünde. They went each summer, with Nanny, Mama and Mama’s personal maid. From Berlin they always got a sleeping compartment in the train that left from Lehrter Bahnhof late at night and arrived at Lübeck next morning. They alighted from the train and watched the porters pile the luggage onto carts. The children were taken to see the locomotive, a huge hissing brute that smelled of steam and oil and of the burned specks of coal that floated in the sunlit air. Omi always met them at the station in Lübeck. But this time she wasn’t there – only the taxi. It was a big one – a Benz sixty-horsepower Phaeton, more like a delivery van than a car – and it could seat sixteen people if they all crammed together. The driver was a white-haired old fellow named Hugo who would laboriously clamber up onto the roof. There, on its huge rack, he’d strap a dozen suitcases, Mama’s ten hat boxes, a travelling rug inside which were rolled a selection of umbrellas and walking sticks and four black tin trunks so heavy that he’d almost overbalance with the weight of them.

The house itself was a gloomy old place with lace curtains through which the northern sunlight struggled to make pale-grey shadows on the carpet. Even in the dusty conservatory that ran the length of the house, the warmth of the summer sun was hardly enough to stir the wasps from their winter torpor.

Omi always wore black, the same sort of clothes she’d worn back in 1891, when Grandfather died. She spent most of the day in the room on the first floor: she read, she sewed, and for a lot of the time she just remembered. The room was furnished with her treasures and mementoes. There were two large jade dragons and a whole elephant tusk engraved with hunting scenes. There was a big photo of her with Opa on their wedding day, and portraits of other members of the family, and there were stuffed birds in glass cases and green plants that never bore flowers. She called the little room her salon and she received her visitors there – although visitors were few – and looked out the window across the Lübeck Bight to the coast and the water that became the Baltic Sea.

Peter and Paul wouldn’t have looked forward so much to their visits had it not been for the Valhalla. The Valhalla was a small sailing boat that had once belonged to Opa. In his will Opa had bequeathed the little boat to a neighbour. But whenever the two Winter boys arrived, the Valhalla was theirs. The neighbour didn’t know his sailing boat was called the Valhalla. On its bow was painted the same name that had been there when Winter bought it from a boat builder in Travemünde: Domino. But for the boys it was always called Valhalla: the hall in which slain warriors were received by Odin.