По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

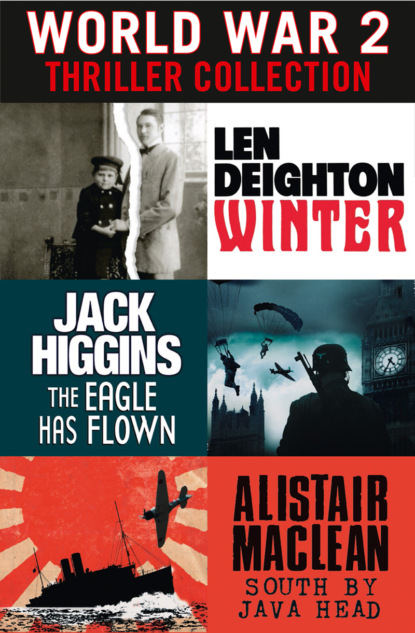

World War 2 Thriller Collection: Winter, The Eagle Has Flown, South by Java Head

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

From his position on the landing, Pauli could squeeze into a space where empty steamer trunks were stored, and from there he could look through an open fanlight and see into the room.

Grandpa was sitting in the big leather chair, alongside the coal fire that was now only red embers and grey ash. Pauli’s father was perched on the edge of the writing desk. His father looked uncomfortable. Both men had cut-glass tumblers in their hands. Grandpa was smoking a big cigar and Daddy was lighting one too. Pauli could smell the smoke as it curled up into his hiding place. Grandpa took the cigar from his mouth and said, ‘Never mind all the stories about a cure for malaria, Harry. If you are trying to raise capital for your bank, it means your bank is in trouble.’

‘It’s not in trouble,’ said Winter. He tugged at the hem of his black waistcoat and silently cursed his Berlin tailor for not knowing that in England it was passé.

‘When people start saying a bank is in trouble, it’s in trouble.’

Harald Winter said, ‘It’s a chance to expand.’

Rensselaer interrupted him. ‘Never mind the bullshit, Harry; save that for the suckers. My friends in the City tell me you’re not sound.’

Winter stiffened. ‘Of course it’s sound. Half the money still remains in German government bonds.’

‘Damnit, Harry, don’t be so naive. It’s not sound because your aluminium factory may not be a success. Suppose the aluminium market doesn’t come up to your expectations? How are you going to pay back the money? Your investors think all their money is in government bonds. It’s bordering on the dishonest, Harry.’

Winter sipped his drink. ‘The electrolytic process has changed aluminium production. The metal is light and very strong; they’re experimenting with all kinds of mixtures, and these alloys will revolutionize building and automobiles, and they’ll find other industrial uses for it.’

‘Sure, sure, sure,’ said Rensselaer. ‘I’ve heard all these snake-oil stories…. There’s always a claim where some guy will strikegold or oil…and it’s always next week. I grew up on all that stuff.’

‘I’m not talking about something that might never happen,’ said Winter. ‘I’m talking about using aluminium alloys.’

‘Aluminium: okay. I made a few inquiries. In 1855 it cost a thousand Reichsmarks per kilo; in 1880, twenty Reichsmarks; now I can buy it for two Reichsmarks a kilo. What price will it be by the time your factory comes into full-scale production?’

‘I’m not selling aluminium, Mr Rensselaer.’ He always addressed his father-in-law as ‘Mr Rensselaer’, always expecting him to suggest he called him Cyrus or Cy as his friends did; but Cyrus Rensselaer never did suggest it, even though he called his son-in-law Harry. It was another example of the way Harald Winter was deliberately humbled. Or that was how it seemed to him. ‘I’ll be selling manufactured components that bolt together to make the rigid framework for airships.’

‘Then why the aluminium factory? Buy your materials on the open market.’

‘I have to have an assured supply. Otherwise I could sign a contract and then be held to ransom by the aluminium manufacturers.’

‘It’s my daughter I’m thinking of, Harry. You haven’t told her that you are going to put every penny you can raise into producing metal components for flying machines. I sounded her out this afternoon: she thinks you’re cautious with money. She trusts you to look after the family.’

Winter drew on his cigar. ‘These zeppelins are going to change the world, Mr Rensselaer. A year ago I would have shared your scepticism. But I’ve seen Zeppelin’s first airship flying – as big as a city block and as smooth as silk.’

‘And as dangerous as hell. Don’t you know those ships are full of hydrogen, Harry? Have you ever seen hydrogen burn?’

‘I know all the problems and the dangers,’ said Winter, ‘but, just as you have your contacts here in London, I have friends in the Berlin War Office. At present the General Staff is showing strong opposition to all forms of airship; the soldiers don’t like new ideas. But the Kaiser has personally ordered the setting up of a Motorluftschiff-Studien-Gesellschaft: a technical society for the study of airships. It’s still very secret, but it’s just a matter of time until the army orders some big rigids from Count Zeppelin.’

‘That’s all moonshine, Harry. I hear that Zeppelin’s second ship, which flew in January, turned out to be a big flop. They say its first flight is going to be its one and only flight.’

‘But Count Zeppelin is already building LZ3, and it will fly in about twelve weeks from now. Make no mistake: he’ll go on building them.’

‘Maybe that just shows he doesn’t know when he’s licked. And who can say how the airships will shape up when the army tests them?’

‘Do you realize how much aluminium goes into one of those airships? They weigh almost three tons. Thousands of girders and formers go into each ring. I’ve done some sums. Using Count Zeppelin’s first airship as a yardstick, I’d need only six-point-seven-three per cent of an airship’s aluminium requirement to break even and pay back the interest.’

Even Rensselaer was visibly impressed. ‘But we’re talking about every red cent you possess, Harry. Why not a smaller investment?’

‘I could have a smaller investment; I could do without the aluminium factory and be at the mercy of my suppliers. I could have half an interest and have only nonvoting shares, but that would mean someone else was making the decisions about who, what, why and where we sell. That’s not my way, Mr Rensselaer: and it’s not your way, either.’

Rensselaer scratched his chin. ‘I’ve spent half my working life trying to talk people out of these kinds of blue-sky investments. But I can see I’d be wasting my time trying to talk you out of it.’ Rensselaer got up from his chair for enough time to flick ash into the fire. ‘J. P. Morgan bought up steel companies to make U.S. Steel, and he’s made himself one of the most powerful men in the U.S., maybe one of the most powerful men in the whole damned world. It looks easy, but don’t think that you can corner the market in aluminium and become the J. P. Morgan of Germany. The European market just doesn’t work that way.’

‘I know that, Mr Rensselaer.’

‘Do you?’ He slumped back into his chair. ‘That’s good, because I meet a whole lot of people who try to get me involved in financing crackpot schemes like that.’

‘It’s just bridging.’

‘It’s not bridging, Harry!’ Suddenly Rensselaer’s voice was louder. Then, as if determined to control his temper, he lowered it again to say, ‘We’re talking about guarantees that will go on until 1916. Ten years! A hell of a lot of things could happen between now and then.’

‘I have most of it, Mr Rensselaer.’

‘You need nearly a million pounds sterling, Harry, and that’s a hell of a lot of dough when you’ve got no collateral that I’d want to try and realize on.’

Winter knew that his father-in-law had decided to let him have the money. He smiled. ‘It’s a great opportunity, Mr Rensselaer. You’ll never regret it.’

‘I’m regretting it already,’ said Rensselaer. ‘I’ve always tried to stay clear of government agencies in all shapes and forms. Especially I’ve avoided armies and navies. Now I’m going to find myself with a million pounds sterling invested in the army of the Kaiser: a man I wouldn’t trust to look after my horses. What’s worse, I’m going to have the security of my investment depending upon his bellicose ambitions.’

Rensselaer knew his words would offend his son-in-law but he was angry and frustrated at the trap he found himself in. When Winter wisely made no reply, Rensselaer said, ‘It’s for Veronica’s sake – you know that, of course – and I’ll want proper safeguards built into the paperwork. I’ll want your life insured with a U.S. company for the full amount of the loan.’

‘It’s the Kaiser’s life you should insure,’ said Winter. ‘My death would make no difference to the investment.’

‘Here’s to the Kaiser’s health,’ said Rensselaer sardonically. He raised his glass and drank the rest of his whiskey.

Winter smiled and decided not to drink to the Kaiser’s health. In the circumstances it would seem like lese-majesty.

Little Pauli crawled out of his hiding place and went slowly upstairs, trying to figure out what the two grownups had been talking about. By the time he found his bedroom again, only one part of the scene he’d witnessed was clear to him. He shook Peter awake and said, ‘I saw Daddy and Grandpa. They were smoking cigars and talking. Daddy made Grandpa drink to the health of His Majesty the Emperor. He made him do it, Peter.’

Peter came awake slowly, and when he heard Pauli’s story he was sceptical. Little Pauli hero-worshipped his father in a way that Peter would never do. ‘Go to sleep, Pauli, you’ve been dreaming again.’ He turned over and snuggled deep into the soft down pillow.

‘I haven’t been dreaming,’ said Pauli. He wanted Peter to believe him; he wanted his big brother to treat him as an equal. ‘I saw them.’ But by the time morning came, he was no longer quite certain.

1908

‘Conqueror of the air – hurrah!’

In Friedrichshafen it was cold, damned cold. There was very little wind – the zeppelins could not take off in a wind – but November is not a time of year when anyone goes to the shores of the grim, grey Bodensee unless he has business there. Across the calm water of the lake, the Swiss side was clearly visible and the Alps were shining in the watery winter sunlight.

Harald Winter had persuaded his wife to stay in the car. It was Winter’s pride and joy. A huge seven-and-a-half litre Italian car, just like the one that won the Peking-to-Paris Road Race with twenty days’ lead! And yet, with its four-speed gearbox, so reliable and easy to use that Winter sometimes took the wheel himself. He’d had it parked down by the waterfront under the trees near the Schlosskirche, so that Veronica would have a good view of the airship and the shed that floated on the lake. She was well wrapped up, and under her feet was a copper foot-warmer that could be refilled with boiling water. And if she got too cold, the chauffeur would drive her back to the Kurgarten Hotel in Friedrichshafen, where the zeppelin people had provided for the Winter family a comfortable suite of rooms.

But Harald Winter was at the lakeside, nearer to the activity. He was excited; he would not have missed this occasion for all the world. Together with his two boys – Peter twelve and Pauli eight – he’d been given a place from which he could see everything. He would have been flying in the zeppelin but for the stringent terms of the life insurance that his father-in-law had made a condition of the loan.

They’d seen the floating shed being revolved to eliminate any chance of a crosswind damaging the airship as it came from out of its tight-fitting hangar. Now they watched as the white motorboat took its distinguished guests out to LZ3; the new modifications made her the finest of the airships. The crowd cheered spontaneously. After the tragic destruction of LZ4 last year – in a gesture that no foreigner would ever understand – the spontaneous generosity of the whole nation brought Count Zeppelin six million marks in donations. Much of the money had been sent within hours of the disaster. So these cheers were not just for the airship. There was something exhilarating in the atmosphere here today. The zeppelin was fast becoming a symbol of a new, exciting Germany, whose scientific inventions, paintings, music, and, more importantly, growing naval strength had made a real nation from a collection of small states. And not just a nation, but an international power of the first rank.

‘That’s the Kaiser,’ whispered Winter to his sons. ‘He’s wearing that long cloak or you’d see all his medals. Next to him is Prince Fürstenberg and then Admiral Müller and General von Plessen. The thin one is the Crown Prince.’

‘Why isn’t Count Zeppelin with them?’ Peter asked. The boys were wearing grey flannel suits, specially tailored for the occasion, and large cloth caps that their mother thought were ‘too grown-up-looking’ for them.

‘He is,’ said Winter. He was wearing a tight-fitting chesterfield and top hat, a formal outfit suited to someone who would be presented to the Kaiser. ‘He’s facing His Majesty, but he’s not wearing his old white cap today; he’s dressed up for the occasion.’