По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

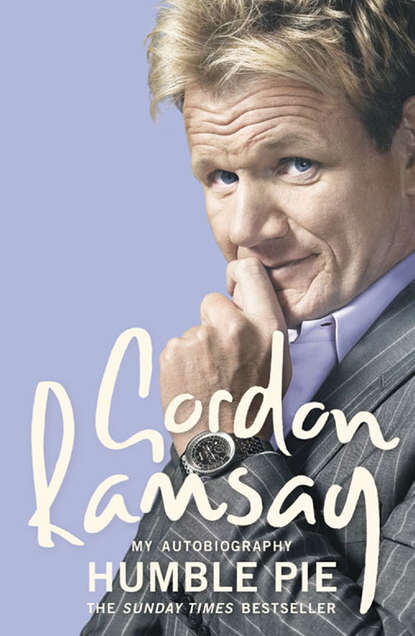

Humble Pie

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

I played for the first team twice, but only in friendlies, or pre-season. In those days, Ally McCoist had just broken into the first-team squad – we still know one another now, though for different reasons, which is really weird – and Derek Ferguson was captain of the under-21s. But it was a bad time for me, stars or no stars. Dad’s duplicity was really getting to me. Then they said: ‘We’re going to continue watching you. We’re really excited. We are going to sign you – but it’ll be next year rather than this.’ Well, that was tough. I knew I was going to go back – how could I not – but by this time, I’d been offered a cooking job in London. Somewhere, I’ve still got the letter offering it to me. It was a new 300-seater banqueting hall that had opened at the Mayfair Hotel called The Crystal Room. They were looking for four commis chefs: second commis, grade two. I don’t know what the fuck that means, even now – it’s a posh kitchen porter, basically. But the salary was £5,200 a year. Anyway, I told them that I wasn’t available to start and went back up to Rangers for the third year in a row.

This must have been the summer of 1984. Half the players weren’t there because they were travelling in Canada, so everything was much more focused on the youth players. Basically, they were deciding who was staying, who they were going to sign that year. Coisty was there, and Derek and Ian Ferguson, whose contracts were well under way. They’d been involved with the club since they were boys, and I suppose that’s all I ever really wanted to do, too: to stay put in one place, and play football, and become a local boy.

But if you’re trying to make it in one of the best teams in Europe, and you don’t even sound Scottish, you’re like a huge, fucking foreigner. Luckily, I was getting big and strong and I could just about handle myself. The training went very well, this time. I remember playing in a reserve team game against Coisty. They always used to hold back two or three first-team players, and then they’d give the inside track about what you were like on the pitch. I had a good game. I was hopeful. I was feeling positive.

The following week, we were playing a massive testimonial in East Kilbride. I couldn’t believe it. I was in the squad, and I got to play. There must have been about 9,000 supporters at the game. The trouble was that they kept moving me around the pitch, playing me out of position. First I was centre back. Then I played centre mid-field, where you’ve got to have two equally strong feet, and you have to be able to twist and turn suddenly. I was really pissed off, and then, just to make things even worse, I got taken off fifteen minutes before the end. They must have made at least seven different substitutions that day. Never mind. I trained for another two weeks, and then I played in another youth team match. Another really, really good game. I was starting to think that I might be in with a chance.

Then, disaster. The pity of it is that my football career effectively came to an end in a training session – one of those bizarre training accidents where you barely realise what it is that you have done. I smashed my cartilage, seriously damaging my knee, and stupidly, I tried to play on. There had been one of those horrendous tackles that makes you even more determined not to give up. I would do whatever I was asked to do, no question. We went on to take penalties with our right foot. I’ll never forget it. We had to put a trainer on our left foot and a football boot on our right. The idea was to make your right foot work constantly. So first there was a penalty competition and then, afterwards, we had to take corners with our right foot. It must have been nearly four o’clock when they finally said, right, we’re going to divide into two teams of eleven and play fifteen minutes each way and I want you all to give it everything you’ve fucking got. By this time, we’d been training all day. Well, that was a big mistake. By the time we finished, I was in a serious amount of pain.

Afterwards, I should still have been resting up, but I tried to get back into the game too quickly. I was out for eleven long weeks, getting more and more paranoid, terrified that someone else would take my place on the bench. But no sooner was I up and running again than I played a game of squash. That was a really dumb thing to do. I tore a cruciate ligament during the game, and was in plaster for another four months. I was worried that I wouldn’t regain my match fitness. Once the plaster came off, I started training again like a demon. But I was still in a lot of pain, though I tried to ignore it. After training sessions, I would spend hours in hot and cold baths, trying to ease the pain, to reduce any swelling. Deep down, I think I knew I was in trouble, but I pushed those kinds of thoughts to the back of my mind. I would tell myself: maybe all players are in this much pain. Or: maybe I can work through it. I was determined to put in a third appearance for the first team, and in order to do that, I had to ignore the message my body was trying to send me.

But come the start of the new season, there was no getting away from it. My leg was just not the same, and this had become apparent to my bosses. Jock Wallace, the club’s manager, and his assistant, Archie Knox, called me into their office one Friday morning to give me the bad news. It was all over for me. I was not going to be signed. I was not going to play European, or even first division football. I remember their words coming at me like physical blows. It was so hard to take. But I was determined not to show how broken I felt inside. Years of standing up to Dad had put me in good stead for this performance. I might have wanted to cry, or to shout, or to punch the nearest wall, but I was damned if I was going to in front of these two. I admired Jock and I had always been intimidated by him. I certainly wasn’t going to let the side down now. I gripped my chair, and waited for the whole thing to be over. In those few minutes, all my dreams died. Part of me was wondering how I would manage to walk out of the room.

They suggested I do more physio, and maybe sign with a different club, one in a lower league. So did my father. In fact, he was pathetically eager that I take this advice. I don’t think he could bear to lose sight of the dreams he had had for me. He wanted the good times to roll. He wanted to be able to boast to his so-called friends, who had always been so much more of a success in life than him. Dad was sitting in his van just outside the ground when Wallace broke the news to me; going out there and telling him was one of the toughest things I have ever done. But I wouldn’t let him have the pleasure of seeing me cry, either. On and on he went: ‘You carry on badgering Rangers,’ he said. ‘You prove to them you are fit again.’ But far harder to take was his lack of sympathy for me. He didn’t have a single kind word for me that day, not even so much as a gentle pat on the shoulder. Later on, he even suggested that I might be exaggerating the extent of my injury. So I went home, shut myself away, and had a good cry. I couldn’t face seeing anyone. I suppose I mourned for what might have been. But I was also certain that I had no future in football. Scrabbling around playing games here and there and working some other day job to pay the bills wasn’t for me. I wanted it all, or I wanted nothing. No matter how much promise I had shown, I was always going to be labelled as the player with the gammy knee. I had to let go of the game that I loved. That was hard because I had come so close to making it, and I felt bitter for a long, long time afterwards. But I was certain that I was doing the right thing in making a clean break: I had the example of my father and his so-called music career to encourage me, didn’t I? There was no way I wanted to be a pathetic dreamer like him for the rest of my life. The very idea disgusted me. I wanted to be the best at whatever I did, not the kind of guy that people secretly laughed at behind his back. I needed a new challenge. The only question was: what would that be?

Looking back on this time, I’m struck, once again, by the cruelty of my father, and the way he dominated everything I did, even my football. I loved the game. But my involvement wasn’t about becoming a famous player with flash cars and flash houses and women hanging on my every word. It had so much more to do with proving myself to my father. I remember one night, when he was very drunk, he said to me that he used to think that I was gay when I was a little boy. I will never forget that. What is striking to me about that now is that he was so full of hatred for the idea that I might be gay; I couldn’t help but wonder why the idea made him feel so threatened. What was his problem?

The film Billy Elliot has an amazing resonance for me. I remember going to see the musical version of it on stage in London with Tana. Fucking amazing. There was a moment – you can probably guess which one – when it took me straight back to my bedroom, to Dad being furious with me and accusing me of being gay. It moved me so much that I could hardly swallow for twenty-four hours. I know that world, where things are so hard. Mum trying to bake bread because we hadn’t even enough money to buy a loaf; us all depending on fucking powdered Marvel milk for months and months on end. No wonder I was so fucking thin. You never forget all that, and when you see the same kind of life up there on the big screen, you have one flashback after another. Not to be self-pitying, but it can leave you in pieces.

Of course, going into cooking probably got Dad thinking all that crap about my being gay all over again. He always thought that any man who cooked had to be gay – and he wasn’t alone. When I started out, this country had no culture of great kitchens. It wasn’t like France – cooking was a suspect profession for a man. You may as well have said that you wanted to be a hairdresser.

When I first started working in a kitchen, I kept the two worlds – football and food – as far apart as I could. One night, when I was at Harvey’s, Coisty came in for dinner with Terry Venables. I didn’t say a word to anyone. I didn’t want the other cooks to know about my life at Rangers, and I didn’t want anyone connected with football to see me in my whites. It seems bloody silly now. But back then, it felt like a matter of life and death. What a long way I have come.

CHAPTER THREE GETTING STARTED (#ulink_3ec78cf7-8cb3-5362-a09e-022906165986)

GROWING UP, THERE wasn’t a lot of money for food. But we never went hungry. Mum was a good, simple cook: ham hock soup, bread and butter pudding, and fish fingers, homemade chips and beans. We had one of those ancient chip pans with a mesh basket inside it, and oil that got changed about once a decade. I loved it that the chips were all different sizes. She used to do liver for Dad – that was the only thing I refused to eat – and tripe in milk and onions; the smell of it used to linger around the house for days and days. Steak was a rarity: sausages and chops were all we could afford. We were poor, and there was no getting away from it. Lunch was dinner, and dinner was tea, and the idea of having a starter, main course and pudding was unimaginable. Did people really do that? If we were shopping in the Barras, and we decided to have a fish supper, we children all had to share. There was no way we would each be allowed to order for ourselves. Later on, when Mum had a job in a little tea shop in Stratford, she’d bring home stuff that hadn’t been sold. We regarded these as the most unbelievable treats: steak-and-kidney pies and chocolate éclairs.

We were permanently on free school dinners. That was terrible. It used to make me cringe. In our first few years, of course, none of the other kids quite cottoned on to what those vouchers were about. But higher up the school it became fucking embarrassing. They’d tease you, try to kick the shit out of you. On the last Friday of every month, the staff made a point of calling out your name to give you the next month’s tickets. That was hell. It was pretty much confirmation that you were one of the poorest kids in the class. If they’d tattooed this information on your forehead, it couldn’t have been any clearer. So yes, I did associate plentiful food with good times, with status. But I’d be lying if I said I was interested in cooking. As a boy, it was just another chore. My career came about pretty much by mistake.

I latched on to the idea of catering college because my options were limited, to say the least. I didn’t know if the football would work out. I looked at the Navy and at the Police, but I didn’t have enough O levels to join either of them. As for the Marines, my little brother, Ronnie, was joining the Army, and I couldn’t face the idea of competing with him. So I ended up enrolling on a foundation year in catering at a local college, sponsored by the Rotarians. It was an accident, a complete accident. Did I dream of being a Michelin-starred chef? Did I fuck! The very first thing I learned to do? A bechamel sauce. You got your onion, and you studded it with cloves. Then you got your bay leaves. Then you melted your butter and added some flour to it to make a roux. And no, I don’t bloody make it that way any more. I remember coming home and showing Diane how to chop an onion really finely. I had my own wallet of knives, a kind that came with plastic banana-yellow handles. At Royal Hospital Road, we wouldn’t even use those to clean the shit off a non-stick pan, let alone chop with them. But we were so proud of them – and of our chef’s whites. I treated my knives and my whites with exactly the same love and reverence as I used to my football boots. I sent a picture of me in my big, white chef’s hat up to Mum in Glasgow. I think she still has it. I was so fucking proud.

Meanwhile, I had a couple of weekend jobs. The first was in a curry house in Stratford – washing up. The kitchen there wasn’t the cleanest place in the world, and they worked me into the ground. Then, in Banbury, Diane got me a job working in the hotel where she was a waitress. Again, I was only washing up, but that was when I first got the idea of becoming a chef. I was in the kitchen, listening to all the noise, and I was fascinated. I couldn’t believe the way people were shouting at each other. I was working like a fucking donkey, but the time used to fly by. I was enraptured.

After a year, one of my tutors suggested to me that I start working full-time, and attend college only on a day-release basis. I’d made good progress. That said, I was by no means the best kid in the class. In college, you can spot the students from the council estate, the ones who are basically middle-class, and the ones whose parents are so in love with their daughters that they send them to cookery school. God knows why. There are three tiers, and you can spot them a mile off. I was in the first group. I didn’t get distinctions, and I wasn’t Student of the Year. But I did keep my head down, and I did work my bollocks off. I pushed myself beyond belief. I was happy to learn the basics. I didn’t find it demeaning at all.

So I started work as a commis at the place where I’d been washing up: the Roxburgh House Hotel. The dining room was pink – pink walls, pink linen – all the waiters were French and Italian and all the cooks were English. My first chef was this twenty-stone, bald guy called Andy Rogers. He was an absolute shire horse. The kind of guy who would tell you off without ever explaining why. Dear God, the kind of food that he encouraged us to turn out. I shudder to think of it. The cooking was shocking, the menus hilarious. Take the roast potatoes. They started off in the deep fat fryer and then they were sprinkled with Bisto granules before they went in the oven, to make sure they were nice and brown. Extraordinary. The foie gras was all tinned.

We used to serve mushrooms stuffed with Camembert. One of the dishes was called a scallop of veal cordon bleu. It was basically a piece of battered veal wrapped around a ball of grated Gruyère in ham. I knew it was all atrocious, even then. I was getting all this information at college, and I would come back and try to apply it. I’d say: ‘You know there’s a short cut. To make fish stock you should only cook it for twenty minutes, otherwise it will get cloudy, and then you should let it rest before you pass it through a sieve, or it will go cloudy again.’ For this, I would get roundly bollocked by the chef. He didn’t give a fuck for college.

I stayed for about six months, and then I got a job at a really good place called the Wickham Arms, in a small village in Oxfordshire. The owners were Paul and Jackie, and the idea was that I would live above the shop, which was a beautiful thatched cottage. Unfortunately, things went pear-shaped there pretty early on. Jackie was in her thirties, I must have been about nineteen, Paul was away a lot; perhaps you can imagine what was going to happen.

Paul was mad about golf, and he loved his real ale. So he’d be off down to Cornwall, in search of these wonderful kegs. I had a serious girlfriend at the time, I’d met her at the college but she was going off to university. So that didn’t stop me. Basically, I was in charge of the kitchen, and a 60-seat dining room, and I wasn’t even properly qualified yet. I was making dishes like jugged hare and venison casserole and doing these amazing pâtés, and just reading endless numbers of cookery books. Locally, everyone loved the food, and it became a kind of hot spot. But I guess that went to my head: I was on my own, completely free, no one checking up on me. I was all over the fucking shop.

One day, while Paul was off on one of his trips, Jackie rang down to the kitchen. ‘Can I have something to eat?’ she said.

‘What would you like?’

‘Just bring me a simple salad, thanks.’

So I got together a salad with a little poached salmon and took it up.

‘Jackie, your dinner is ready.’

And she opened the door – stark bollock naked. I put the tray down, and went straight into her bedroom.

For the next six months, I led a kind of double life. There was Jackie, my teacher, and Helen, my pupil. You know what it’s like when you’re young. It’s awkward and clumsy. Sometimes, at least before I met Jackie, I used to feel that sex was like sharpening a pencil. You stick it in there, and grind it around. But Jackie was teaching me all these things, and it was amazing. The trouble was that Helen got some of the fringe benefits, which meant that she was falling more and more in love with me.

At first, Paul would only be away for a couple of days at a time. Then he started going on golfing trips to Spain for more like a week. That’s when it all got too much. It was getting heavy. Fucking heavy. Jackie told me that she loved me. The truth is that I loved making the jugged hare more than I did having sex with the boss’s wife, but the only reason I was in a position to buy and cook exactly what I wanted was precisely because I was shagging her. Things weren’t exactly going to plan and it was all getting too nerve-racking for me: that he might notice, that we might get caught, the fact that she was always telling me she was in love with me. So I told them that I was leaving to go and work in London. She went bananas.

I actually went back to the Wickham Arms two years later, for a mate’s twenty-first. Someone must have told Paul because, while she was still being very flirtatious, he was clearly not too pleased to see me. I was in the kitchen, talking to the new chef, telling him how good I thought the buffet was. There was a carrot cake sitting there and, without thinking, I stuck my finger in it. Well, one of the waitresses must have snitched on me to Paul because a split second later, he came running in and shoved me hard against the wall.

‘I should have fucking done this three years ago,’ he said. ‘You know what the fuck I’m on about.’

He then took a swing at me, but fortunately one of my mates intervened, which gave me enough time to make a very sharp exit. So I ran from the kitchen, jumped in the car and disappeared into the night. Hilarious. The next time I saw them was quite a long time later, when they turned up at Aubergine in the early part of 1998. They’d opened a new restaurant in a village in Buckinghamshire, and they brought their chef to meet me at Aubergine. By then, a lot of water had passed under the bridge. They had rung me, told me that he was a big fan of mine, and asked if they could come by. I said, sure, of course. It was embarrassing – I mean, I’d moved on, I wasn’t just poaching salmon and chopping aspic any more – but I made out it was good to see them all. The trouble was, they got pissed and a bit leery and then, when they missed the train back to Buckinghamshire, they started demanding that I offer them a bed for the night. We did try to ring around and find them a room, but hotels were £250 per night, which seem to make them even more aggrieved. I don’t know what they expected me to do – ask them back to sleep on the floor of my flat as well as cook their food? Well, I wasn’t having that. Tana was pregnant at the time, so I sent out their dessert and then I fucked off.

At half-past one in the morning, I got a call from Jean-Claude, my maître d’. He was screaming at me down the telephone. This chef of theirs was holding him over the bar, demanding that the arrogant fucker who left without saying goodbye – i.e. me – come on the line. About fifty minutes later, I rocked up on my motorbike. I thought I better had, and I was right. It was total mayhem. There was Mark, my head chef, fighting with Paul, and Paul’s new chef fighting with Jean-Claude. Naturally, I just could not stand by and watch Aubergine get trashed or my staff take a beating. But they both moved towards me before I had time to think. Paul was going: ‘I trusted you. How dare you – you shagged my wife!’ All my staff were thinking: WHAT? I could see it on their faces. The resulting mêlée caused major headlines when the Old Bill arrived because there was so much blood everywhere. We all got taken off to make statements and then, when the whole thing was written up in the London Evening Standard, predictably, it was me who was supposed to have thrown all of the punches. It was all: ‘I came to meet the great master and instead found an arrogant bastard’, ‘Brawl that wasn’t on the menu’ and ‘Ramsay punched my husband in the mouth’. That kind of rubbish. I had to take legal action to clear that one up. I kept my powder dry until all the other papers had followed suit and then I issued proceedings. I won, of course. As for Paul, he sobered up pretty fast once he got back to Buckinghamshire. He sent me a fax apologising. That was the end of that.

To be fair, they really looked after me, those two. Before it all went wrong. I mean, I wasn’t exactly as sweet as pie. Of course I wasn’t Mr Innocent. I was a little fucker, actually – no mum and dad around, a place to live, a girlfriend, thinking I was the dog’s bollocks. I would borrow my girlfriend’s father’s car all the time, even though I hadn’t passed my test. I used to leave the kitchen at half-past one in the morning and drive down the country lanes, over to Helen’s. One night, I left the pub in this car, and turned a corner only to be met by two sets of headlights: one car overtaking another on a bend. I pulled out of the way, but they hit the back of my car and it went into a spin, straight into the very prettily beamed sitting room of the nearest cottage. My head was cut, my knees were cut and all I wanted to do was to make myself scarce as quickly as possible because, of course, I shouldn’t have been driving at all. My test was still five weeks away. So that’s what I did – I absconded. Unfortunately, the police picked me up three hours later, hiding out in some fucking manure dump.

Naturally, I was prosecuted. As it turned out, the case came up the day after I was due to take my test. My solicitor told me that he strongly advised me to pass it because it would help my case in court, but I failed and so, in the end, I was banned for a year even though officially I wasn’t actually able to drive. I was also fined £400. About five years ago, I got a solicitor’s letter from the new owners of the cottage I’d smashed up; they were still trying to claim the £27,000 worth of damage I caused. Pass the place today and, in the spot where I made my unannounced house call, you can see that the bricks are still two different colours. Yes, I might have been an extremely ambitious young man, but I was also a bit of a tearaway. I can’t deny it. I don’t really blame Paul for wanting to beat me up. Any man would have done the same in his position.

So, to the starry lights of London. I was second commis, grade two, at the Mayfair Hotel, in its new banqueting rooms, as planned. I stayed about sixteen months, and I learned a lot. I used to make the most amazing sandwiches, the smoked salmon sliced incredibly thinly, because I had to do room service as well. On my day off, I would work overtime without getting paid, just for the chance to work in what we used to call the Château – the hotel’s fine-dining restaurant, where all the staff was French. If you fucked up during service, you had to work in the hotel coffee shop. That was the punishment. It was a tough place. If someone called in sick, you could easily end up working a twenty-four-hour shift. You’d work all day in the restaurant, and then during the night you’d man the grill and do the room service. At half-past four in the morning, all the Indian kitchen boys would sit down and have their supper, and then they’d go and pray for an hour, and you’d already be doing prep for the next morning’s breakfast. In those days, a hotel’s scrambled eggs were done in a bain-marie. You whipped up three trays of eggs and then you put them, along with some cream and seasoning, into the bain-marie so it could cook slowly, over a period of two and a half hours, at the end of which it was like fucking rubber.

Naturally, like a true goody two-shoes, I said: ‘Look, I’m on breakfasts this morning. I’m going to make all the scrambled eggs to order, chef.’ And that’s exactly what I did, though I got fucked when I came back from my day off because there’d been so many complaints about how slow the breakfasts had been. ‘But chef,’ I said. ‘I may have been a bit slow, but at least they weren’t rubber eggs. They were freshly made to order.’ He wasn’t having any of it. ‘I don’t give a fuck,’ he said. ‘We had to knock about twenty-five breakfasts off bills.’ I got such a bollocking – a written warning, in fact. But when he gave it to me, in a funny way, it was helpful. It was there in black and white that I was working in a place that wasn’t for me – a place where you got a warning for failing to cook crap scrambled eggs. I knew I had to get out.

In those days, there was a really cool restaurant called Maxine de Paris, just off Leicester Square, and I’d heard that they were opening a new restaurant in Soho called Braganza. So I got a job there as a sort of third commis chef, though I didn’t stay long because all the food went in a dumb waiter, rather than being picked up straight off the pass by a human being, which meant it was always a bit cold, and I just couldn’t come to terms with that. But there was an amazing sous chef there called Martin Dickinson – now the head chef at J. Sheekey – who’d worked at a restaurant called Waltons in Walton Street, a Michelin-starred place, and he was just phenomenal. I suppose that’s when I started thinking that Michelin stars were the Holy Grail, and that I wanted to work in a serious restaurant. Because Martin seemed like a God to me.

‘Get yourself into a decent kitchen,’ he told me. ‘This place isn’t for you. Trust me, you don’t want to be working in a place that serves smoked chicken and papaya salad. Get the fuck out of here.’

I would have worked it out somewhere down the line, but I owe it to Martin that I moved so quickly. I went up to the staff canteen, which was just a grotty little room, really, where all the chefs would smoke, and I grabbed a magazine and I took it out into the garden in Soho Square. ‘Christ,’ I said to myself. ‘There’s Jesus.’ Because on its cover was a photograph of Marco Pierre White, all long hair and bruised-looking eyes. I was nineteen. He was twenty-five. He’d come from a council estate in Leeds and then, when I looked at who he’d worked with and where…Nico Ladenis, Raymond Blanc, La Tante Claire and Le Gavroche. I thought: fuck me, he’s worked for all the best chefs in Britain. I want to go and work with him.

I phoned him up then and there.

‘Where are you working now?’ he said. So I told him.

‘Well, it must be a fucking shit hole because Alastair Little is the only place that I know in Soho, and if you’re not working there then don’t bother coming.’

I wasn’t sure what to say to that, so I told him, without even really thinking about it, that I was about to go to France because I wanted to learn how to cook properly.

‘Have you got a job out there?’ he asked.

‘No, not yet.’

‘Then come and see me tomorrow morning.’

I left the phone box and went back to the restaurant. I couldn’t stop thinking about what he’d said.

I turned up at what would become the legendary Harvey’s the following day, as requested. We’re talking about the earliest days of the restaurant. It had only been open about six months, and it would be another six months before it got its first Michelin star.