По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

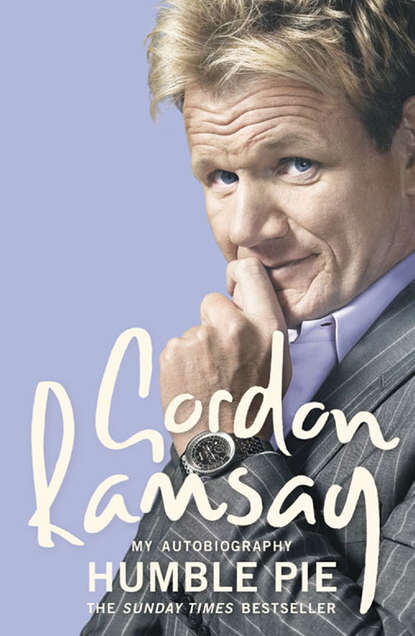

Humble Pie

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Until I was six months old, we lived in Bridge of Weir, which was a comfortable and rather leafy place in the countryside just outside Glasgow. Dad, who’d swum for Scotland at the age of fifteen – an achievement that went right to his head, if you ask me – was a swimming baths manager there. And after that, we moved to his home town, Port Glasgow – a bit less salubrious, but still okay – where he was to manage another pool. Everything would have been fine had he been able to keep his mouth shut. But he never could. Sure as night followed day, he would soon fall out with someone and get the sack; that was the pattern. And because our home often came with his job, once the job was gone, we were homeless. Time to move. That was the story of our lives. We were hopelessly itinerant.

What kind of people were my parents? Dad was a hard-drinking womaniser, a man to whom it was impossible to say ‘no’. He was competitive, as much with his children as with anyone else, and he was gobby, very gobby – he prided himself on telling the truth, even though he was in no position to lecture other people. Mum was, and still is, softer, more innocent, though tough underneath it all. She’s had to be, over the years. I was named after my father, another Gordon, but I think I look more like her: the fair hair, the squashy face. I have her strength too: the ability to keep going no matter whatever life throws at you.

Mum can’t remember her mother at all: my grandmother died when she was just twenty-six, giving birth to my aunt. As a child, she was moved around a lot, like a misaddressed parcel, until, finally, she wound up in a children’s home. I don’t think her stepmother wanted her around, and her father, a van driver, had turned to drink. But she liked it, despite the fact that she was separated from her father and her siblings – it was safe, clean and ordered. The trouble was that it also made her vulnerable. Hardly surprising that she married my father – the first man she clapped eyes on – when her own family life had been so hard. She just wanted someone to love. Dad was a bad lot, but at least he was her bad lot.

By the age of fifteen, it was time for her to make her own way in the world. First of all, she worked as a children’s nanny. Then, at sixteen, she began training as a nurse. She moved into a nurses’ home – a carbolic soap and waxed floors kind of a place – where the regime was as strict as that of any kitchen. In the outside world, it was the Sixties: espresso bars had reached Glasgow and all the girls were trotting round in short skirts and white lipstick. But not Mum. To go out at all, a ‘late pass’ was needed, and that only gave you until ten o’clock. One Monday night, she got a pass so that she could go highland dancing with a girlfriend of hers. But when they got to the venue, the place was closed. That was when the adrenalin kicked in. Why shouldn’t they take themselves off to the dance hall proper, like any other teenagers? So that was what they did. A man asked Mum to dance, and that was my father, his eye always on the main chance. He played in the band there, and she thought he was a superstar. She was only sixteen, after all. And when it got late, and time was running out and there was a danger of missing the bus, all Mum could think of was the nightmare of having to ask the night sister to take her and her friend back over to their accommodation. Then he and his friend offered to drive them back in his car. Well, she thought that was unbelievably exciting, glamorous even. He was a singer. She’d never met a singer before.

After that, they met up regularly, any time she wasn’t on duty. When she turned seventeen, they married – on 31 January, 1964, in Glasgow Registry Office. It was a mean kind of a wedding. No guests, just two witnesses, no white dress for her, and nothing doing afterwards, not even a drink. His parents were very strict. His father, who worked as a butcher for Dewhursts, was a church elder. Kissing, cuddling, any kind of affection was strictly forbidden. My Mum puts a lot of my father’s problems in life down to this austere behaviour. She has a vivid memory of a day about two weeks after she was married. Her new parents-in-law had a room they saved for best, all antimacassars and ornaments. Her father-in-law took Dad aside into that room, and her mother-in-law took Mum into another room, and then she asked Mum if she was expecting a baby.

‘No, I’m not,’ said Mum, a bit put out.

‘Then why did you go and get married?’ asked her new mother-in-law.

I’ve often asked Mum this question myself. It’s a difficult one. I’m glad I’m here, obviously. But my father was such a bastard, and he treated her so badly, that it’s hard, sometimes, not to wonder why she stayed with him. Her answer is always the same. ‘He wanted to get married, and I thought “Oh, it would be nice to have my own home and my own children”.’ But she knew he was trouble, right from the start.

Ten months later, my sister Diane came along, and Dad got the job at a children’s home in Bridge of Weir. They were given a bungalow on the premises and my poor mother really did think that all her dreams had come true. There was a swimming pool in the grounds, where he was an instructor and manager. According to Mum, it was lovely – idyllic, even. Then it started – the drinking and the temper. She found out that even as they had been getting married, Dad had been on probation for drinking and fighting – though he told her that it wasn’t his fault and, like an idiot, she believed him. She was madly in love, you see. The violence against her started soon after that. He would slap her about and, not having had any other experience with men, she assumed that this was what every woman had to put up with. When her father told her that Dad was bad, she refused to believe him. She’d pay a visit home and, when she took off her coat, there were bruises on her arms, and maybe a cut to her eye or her lip.

‘Oh, I just banged into a cupboard, Dad,’ she’d say. He’d accuse her of telling lies, of covering up. But she was deaf to it all, of course.

Next was the job in Port Glasgow. The prodigal son returns. Dad had all sorts of big ideas about that – his swimming career meant that everyone in the town knew him. They got a nice council house, and I think Mum felt quite settled. But Dad was all over the place – ‘fed up’ he used to call it, a pathetic euphemism. The womanising got steadily worse – he’d go out at night, and not come back until the morning. Then he’d get changed and go straight off to the pool to work. By now, I was around, and Mum was pregnant with my brother, Ronnie. One morning, Dad came home and announced that his car had been stolen. He made a big show of phoning the police to report it. Of course, it was complete bollocks. What had actually happened was that he’d been with a woman, had a few drinks, and knocked down an old man in what amounted to a hit-and-run. Despite his best efforts, it wasn’t long before the police found out and it was all over the papers. There was nothing else for it. Port Glasgow wasn’t a very big place, and it was certainly too small for us now. We had to leave, literally overnight. Diane was toddling, I was in a pushchair, and Mum was pregnant. But did he care? No, he didn’t. It was straight on the train to Birmingham, and who knows why. It could just as easily have been Newcastle, or Liverpool. He may as well have stuck a pin in a map, at random. We knew no one. We spent the night at New Street Station, waiting for the sun to come up so that Dad could walk the streets, looking for somewhere to live. What a desperate sight we must have made; you can all too easily imagine people walking past, looking down at the pavement in their embarrassment.

We found a room in a shared house. Amazingly, Dad only got probation and a fine for the hit-and-run, and he soon picked up a job as a welder. The room was horrible, or so Mum tells me, but we just had to make the best of it. We shared a kitchen – in fact, a cooker in the hall – and a bathroom with another family. Meanwhile, Dad joined an Irish band, and all the usual kinds of women were soon hanging onto his every word. If he went out on a Friday night, you were lucky if you saw him again before Sunday. Needless to say, the welding soon went by the way. He wanted to spend more time with the band; he was convinced, despite all evidence to the contrary, that he was going to be a rock-and-roll star. Even at such a young age, these fantasies of his would make me sick. We’d spend time with him going from market to market looking for music equipment. The money he used to spend was extraordinary, and hard to take. There we’d be, looking at these Fender Stratocasters and Marshall amplifiers – the fucking dog’s bollocks of the music world – and we’d be dressed in rags. All our clothes were from jumble sales, our elbows and knees patched over and over again. How did he fund his shopping habit? Loan sharks, mostly. His debts still come back to haunt me now – our names are the same, and I’ll occasionally get investigated by companies trying to recoup the cash he owes them.

The older I got, the harder this kind of treatment got to bear. I remember when Choppers and Grifters were the big things. Well, of course, we never, ever had a new bike. On birthdays, I used to get a £3.99 Airfix model kit. However much I enjoyed putting those things together, you could tell they’d come from somewhere like the Ragmarket, which was Birmingham’s version of the Barras. There’d be half of it missing, or the cardboard box it came in would be so wet and soggy that you wouldn’t have wiped your arse with it. Christmas was terrible. When we were older, Mum always used to work in a nursing home, doing as much double-time as she could, sometimes not even coming home on Christmas Day. I used to dread Christmas.

And then the bailiffs would show up. We’d be evicted, Dad’s van would be loaded up, and that would be it. Off to the nearest refuge, or round to the social services pleading homelessness. He was always telling them that he was ill, trying to get sickness benefit. In reality, though, he’d be out gigging three or four times a week.

As a teenager, I used to be ashamed of some of the places we lived. We always seemed to end up in the worst of places: the ones that were riddled with damp, with nails exposed everywhere, the ones that had been left like pigsties by other families. I never used to let on to girlfriends – I’d make them drop me off round the corner. It wasn’t so much that I was embarrassed about living on an estate, or in a tenement block. It was more the state of our home itself. Every time he got violent, any ornament, any present we’d bought for Mum, a vase or a picture frame – anything nice – would be smashed or thrown through a window or destroyed, simply because it belonged to her.

I think we built up a lot of insecurity as children. I used to find it so intimidating, walking into yet another new school. Academically, we were never in one place long enough to develop any kind of attention span – and in any case, Dad was hardly the kind of man to insist on you doing your homework. Only poofs did homework. The same way only poofs went into catering. No, he was much more interested in trying to turn us into a country version of the Osmonds. Diane, Ronnie and Yvonne, my younger sister, all sing and play musical instruments. They didn’t really have any choice about that, Dad was obsessed. But something in me wasn’t having it, and I never went along with his plan. That’s not to say I wasn’t just as scared of him as they were. My tactic was to keep my head down and my nose clean. I never drank or smoked, and when I was asked to lug his bloody gear about the place, I just got on with the job. It’s ironic, really, that people think of me as so forceful and combative, a real aggressive bastard, because that’s the precise opposite of how I was as a kid. Until I was big enough to take him on in a fight, I wouldn’t have said ‘boo’ to a goose.

His favourite punishment was the belt. You’d get whacked on the back of your legs with it for something as innocent as going into the fridge and drinking his Coke. I say ‘whacked’. The truth is, I would get completely fucked over for that sort of thing. But what would really set him off were lies. I’d lie about things because I was too scared to tell him the truth, ‘Yeah, Dad, it was me who went in the fridge and took your Coke’ – and then he’d go absolutely fucking ballistic. Of course, what I didn’t realise at the time was that it wasn’t so much the Coke he was bothered about as the fact that he wouldn’t have a mixer for his precious Bacardi. He was the kind of drinker who couldn’t open a bottle without finishing it. You’d watch the stuff disappear, and your heart would sink.

Yvonne was born in Birmingham. One night, when Mum was six months pregnant, a neighbour had to call the police as Dad was dishing out some domestic violence on Mum. He was taken away. Mum was taken to hospital and ended up signing consent forms for the three of us to be taken into a children’s home for ten days. She visited every day. Then Dad was released and he came back home.

Next stop was Daventry, where we had quite a nice council house. It even had a garden. This time, Dad got a job as a rep, but he was still doing his band work and, thanks to the buying of yet more equipment, the debts were building. One day, he told Mum to pack – only the belongings she could fit in his precious van – and we were off again, to Margate where, for a time, we lived in a caravan. He never explained, or tried to justify his behaviour. We did as we were told. That was easily the worst place we ever lived, horrendous. I shudder to think of it. We didn’t even have enough money for the gas bottle to keep the place warm. The rain just came pelting down, while inside we shivered, and wondered how long we were going to be there. We were saved by the council, who put us back into a bed-and-breakfast.

Then it was back up to Scotland again, followed by another stint in Birmingham, and then on to Stratford-upon-Avon. Dad had somehow managed to get another job at a swimming pool. But he couldn’t settle. Off he’d go: off to France, to America. He never sent money home; it was up to Mum to earn our keep. When he came back from his stint abroad, we moved to Banbury, Oxfordshire, where he was going to run a newsagent’s shop. Everything was great for a while. We lived above the shop, and the guy who owned it was lovely. This was Dad’s big chance to get it right, if you ask me. But no, he had to screw it all up. One day, while I was getting something out of the fridge, I noticed that the lining of the door was loose. Unnaturally loose. And something was hidden in there – a wad of cash, it must have been at least £300. I remember feeling very sick, I nearly threw up then and there. Dad was on the fiddle. Not long after that, of course, the owner found out, and we were out on our ear again.

So then it was back up to Scotland – Glasgow. Dad had heard that the country and western scene was better up there. But I was a teenager by now, and I decided not to go. The council gave Diane and me a flat and so we stayed put. I was doing a catering course at college, sponsored by the local Round Table who’d even helped me to buy my first set of knives – but, in any case, I don’t think Dad wanted either of us around. He just couldn’t control Diane the way he’d controlled Mum, and that left him feeling frustrated because in the old days she’d sung with him, been dragged around all the seedy clubs. He had thought she was his, and when it turned out that she wasn’t, that she had a mind of her own, he just couldn’t take it. Later, when Diane got married, she didn’t want him anywhere near her. It was me who gave her away.

As for me, I was public enemy number one. Up in Glasgow, Mum would have to sneak out of the flat if she wanted to ring me. I certainly wasn’t allowed to ring her. I had finally crossed a line when I was fifteen. I was going out with a girl called Stephanie, and one night I came back late – too late, in his eyes.

‘Get your stuff out of my house, and go and live with her,’ he said.

‘I’m sixteen next week,’ I said. ‘I can go where I like.’

I’d already been given some kind of big radio for the upcoming birthday, and he threw it at me, from the top of stairs. ‘I can’t believe you’ve done that,’ I said. ‘You know damn well that Mum bought it for me.’ I knew she’d got it on hire purchase, which was costing her £8 a month, and I couldn’t bear it. ‘I’d rather you did that to me than to something that hasn’t even been paid for,’ I said.

At that, he came storming down the stairs. At first, I stood my ground. Then I saw the look in his eyes. That was why I bolted, and I’m not ashamed to admit it. I don’t think that I would be here today if I’d stopped and tried to confront him. For the first time, I felt that he really might kill me. I remember him teaching me how to swim by holding my head under the water for minutes on end – I’d end up struggling and gasping for air – so I’d always known he was a sadistic bastard. But I saw something different in his eyes that day – a glint that chilled me. There was nothing there. It was a kind of madness.

Of course, once Diane and I were out of the way, he turned his attention to whoever else was available. Ronnie was his pal, mostly, so now it was Yvonne’s turn to take the sort of treatment that I had suffered previously.

By that time, I was already trying to make headway as a cook, on the first rung on the ladder, busting my nuts in a kitchen, and it was unimaginably painful – hearing this stuff from Mum, her voice down the telephone. Yvonne had grown up more quickly than the rest of us – she had a baby in her teens, and she was a real ‘ducker and diver’, but he just pushed her too far, there was too much pressure, and she was going under.

Meanwhile, Mum was still getting knocked about. She was working in my Uncle Ronnie’s shop in Port Glasgow – he was a Newsagent – and she’d come in early in the morning, sometimes not having been to bed at all, with bruised lips and black eyes, and my uncle would say: ‘Oh, Helen, you can’t serve the customers looking like that,’ and she’d say: ‘Well, it was your brother that did this to me.’ But, of course, no one intervened. It was a different time then. Domestic violence was still considered a private matter, something for couples to sort out between themselves.

‘That’s bloody terrible,’ he’d say. ‘You should hit him back.’

Fat lot of good that advice was. Things got so bad that Mum finally worked up the courage to leave him, and the council gave her, Ronnie and Yvonne a flat. But Dad was soon back, pleading forgiveness, promising that everything would be different. And so it would be, for a few weeks. Then he’d start sliding again, back to his old ways, all this anger always pouring out of him. Oh, he was good at crying crocodile tears, but his heart was an empty space where all the normal feelings a man has for his family should have been.

Next, they embarked on some kind of house swap, and the four of them ended up in Bridgwater in Somerset. Same old story…No sooner had they settled in than Dad was off again – this time on a cruise ship. He took Diane with him, to sing, which put Mum’s mind at rest a little because even after everything he’d done to her, she was still worrying that he would run off with someone else, and she had this idea that a cruise would be full of beautiful women. Diane was engaged by this time, and her fiance and Mum saved up to go out and meet the ship in Venice. Mum worked so hard – she had three part-time jobs on the go all at the same time. But when they got there, no sooner had they boarded the ship than Dad had some big, drunken argument with the man who was in charge of the entertainment. This ended with Dad, in a fit of pique, sabotaging all the ship’s musical equipment, at which the captain told him he had to leave. They all came back to London by bus – a fine end to Mum’s dream trip. Did he feel bad about this? Did he feel guilty? Not at all. He had got his revenge, and that was all that mattered.

It was in Bridgwater that he committed the final transgression, and departed our lives – almost for good, if not quite. It’s a time I cannot think about without feeling the blood pulsing in my temples, though I was not even there when it happened. I’m not sure what I’d have done if I had been.

Dad had had a couple of drinks, but he certainly knew what he was doing; this attack was calculated, clever even, not some dumb, drunken rage. He came home from work one night, and he just started. There was no ‘trigger’. Mum was in bed, with a mug of hot milk. He poured it all over her, even as she lay there, leaving bad scalding to her chest. Then he dragged her downstairs, and the beating started. By the time the ambulance arrived, she looked like she’d done five rounds with a heavyweight boxer. Her eyes were completely closed, her face swollen and pulped. First, she was taken to a hospital, then to a refuge. Dad, of course, didn’t stay to face the music. He disappeared at the first sound of a police siren.

A few days later, I finally tracked him down. He was with a woman called Anne, whom he would later marry.

‘Mum’s been in hospital for three days,’ I said. ‘And she’s still wearing sunglasses.’

‘Well, she asked for it,’ he said.

That was when the social services and all the other authorities got fully involved, and a restraining order was taken out on him. He wasn’t allowed anywhere near the house.

But when Mum went home, she found everything that she had built up and saved for smashed to smithereens. He hadn’t left as much as a light bulb intact.

Worst of all, Dad had left a note on the mantelpiece. It said: ‘One night, when you are least expecting it, I’ll come back and finish you off’. Even after the restraining order came into effect, there were some evenings when Mum would be sitting in alone and the phone would ring and she’d hear his voice telling her that he was on his way. Many nights, you would have seen a patrol car parked outside the house, just in case. How she slept, I’ll never know.

Journalists have often asked me whether I loved Dad, whether I had any love at all in my heart for him. The truth is that any time I tried to get close, I’d just come up against this competitive streak in him. Later, my feelings for him hardened into hatred. Everything he did, I was determined to do the opposite. I never wanted to follow in his footsteps, and that’s why I never picked up a fucking guitar, and that’s why I never sat at the fucking piano. Were there any good times? Not really. I suppose the only thing that I really admired about him was the fact that he was a fisherman. He was a great fisherman, there’s no two ways about it. But even that got tainted by all the other stuff.

Ronnie was good at keeping Dad’s secrets, but I made the mistake of telling Mum exactly what he used to get up to. After that, I was never taken fishing again. We used to go to this campsite on the River Tay in Perth – salmon fishing. Ronnie and I would be sitting on the riverbank at nine o’clock at night on our own, fishing, while Dad and his mate Thomas would be out drinking. He’d give us a fiver between us, and tell us to keep ourselves amused. I remember one time when the weather was bad, it was raining heavily, and we’d booked into this little bed-and-breakfast. That night, Ronnie and I ended up sleeping in the bathroom because Dad had brought some woman back. I can’t have been older than twelve at the time.

After a while, Dad went off to Spain, and I didn’t see him for many years. I was too busy trying to make a success of my life, but even if I hadn’t been working every hour God sent, I had no real wish to see him. Dad, though, had a way of turning up when you least expected him, like a bad penny. It was towards the end of 1997. I was busy trying to win my second Michelin star by this point – which should give you some idea of how much time had passed – when I got a call from Ronnie telling me that Dad was in Margate. He’d had an argument with Anne, and Anne’s sons, and he’d upped and left.

I called him on the number Ronnie had given me – I don’t know why. He sounded very low.

‘I’m here to see my doctor,’ he said.

‘Come on,’ I said. ‘Why are you really here?’

‘No, I’m back just to have a check-up.’ There was a pause. Then he said: ‘Can I see you?’

‘Yeah, yeah, I’ll come down.’

It had been a difficult year. My wife, Tana, and I were expecting our first baby. And I was involved in all sorts of legal wrangles over my restaurant, Aubergine. Still, I drove down there. There was something in me that couldn’t refuse his request. We were to meet on the pier where we used to go fishing back when we had lived in the town ourselves, so I knew exactly where he’d be. I got out of my car and I saw this old, frail, white-haired man with bruises on his face, and marks on his knuckles. I felt stunned. This was the man I’d been scared of for so long, brought so low, so pathetic and feeble.

We went and had breakfast in a little cafe. The waiter came over and asked us what we would like and, straight away, Dad started into me, telling me that when I was at home I always used to steal his bread. The words came out of nowhere. Another unwarranted attack.