По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

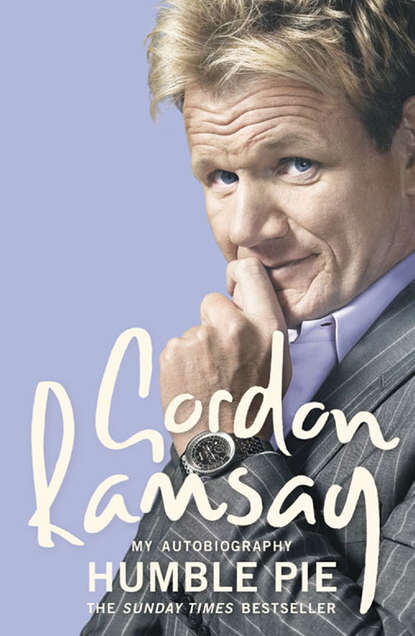

Humble Pie

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘What’s happened to you?’ I said.

‘Oh, Anne and I separated, and I had an argument with one of her sons and he tried to have a go at me.’

‘Look at the state of you. Where are you living?’

He pointed at the car park, and there, as ever, was his Ford Transit van. We went out and I opened it up and inside there were all his possessions: his music equipment, his clothes, and these silly lamps – paraffin lamps – and an inflatable camp bed in the back with these awful net curtains in the windows.

We finished our breakfast, and we went for a walk on the pier, and it was so sad. So I went to the bank, and I got out £1,000 and I gave it to him for the deposit on a flat. I thought that at least I could do the right thing by him. And that’s what he did, he got a little one-bedroomed basement flat. A week later, I went back to see him again. He told me that he was going to be on his own for Christmas. I was in two minds as to what to do. Then I decided: this is not the right time to introduce him to Tana. I felt sorry for him, real pity, but nothing more. And anything I did feel had nothing to do with him being my father; I just felt sorry that a man had to be on his own at that time of year. It seemed so desolate, so bleak.

On Christmas Eve, he telephoned. Anne was coming over to spend the week with him, and they were going to try and resolve their differences. That was the last time I ever spoke to him. Looking back, I wonder if he knew that his time was running out. He’d gone back to Margate because that was where he’d gone on holiday with his parents, as a boy. Perhaps it had happy memories for him. It certainly didn’t for me. Driving back to London after that last visit, I cried my eyes out. What a waste of a life.

After hearing that he and Anne had made up, I booked him a table at Aubergine for the 21st of January, 1998. That was going to be a big, big day for me. First of all, that was Michelin Guide day. The new edition. Second, I was going to introduce this guy, my father, to all my staff. I’d spoken of him so little, most of them didn’t even know I had a father. The truth is that he embarrassed me. When I was eighteen, a girlfriend gave me a gold chain, a massive gold chain – bling before bling was invented – and Dad was envious of it, so incredibly envious. One day he asked me if he could wear it. So I gave it to him. That was the kind of power he had because at the time I loved it half to death. Later, I remember shuddering, seeing him look like some East End spiv, dripping in gold. There was my chain, and sovereign rings, and chunky gold bracelets, all topped off with a white leather jacket. I had never known how to describe this man to anyone, let alone my staff. I’d reinvented myself, I suppose. I’m not ashamed of that. I’ve never tried to pretend anything else. All I knew was that I didn’t want to be like him, and any time I came even close to doing so, I would put the fear of God into myself. My father was in some box that, metaphorically speaking, I’d hidden in a dusty corner of the attic years ago.

And then there was my fear of being used. A while before he came back to England, during a busy service at Aubergine, someone came to me saying I had a phone call from my brother-in-law. At the time, I didn’t have a brother-in-law.

‘Dave, here,’ said the voice.

‘Look, Dave,’ I said. ‘I’m fucking busy right now. I haven’t got time for pranks. You can call me back at fucking midnight.’

But he persisted. He refused to get off the line.

‘Look, Dave,’ I said, again. ‘I don’t know who the fuck you are but this is not the right fucking time. I’m not fucking happy.’

‘Well, I don’t care where you are or what you’re cooking,’ said the voice. ‘My Mum is married to your dad.’

Then it clicked. That, you see, was how little I thought of Dad, and how little I knew about his new life. The voice said: ‘I read that you do consultancy work for Singapore Airlines and my watch is from Singapore, and I can’t get a battery in this country. Is there any chance you could get one for me next time you are out there?’

Perhaps you can imagine how I felt.

‘Are you taking the fucking piss?’ I said.

I put down the phone. Some guy I’d never even met ringing me in the middle of service to ask me to get him a new battery for his watch. I simply could not believe it.

It was New Year’s Eve when we heard that my father died. The family were all in London, staying with me and Tana. It must have been about 3.30 a.m. We’d been in bed for an hour. Then the phone rang. I woke up and answered it and all I could hear was screaming. At first, I thought someone was trying to wish me a Happy New Year, but this person was in hysterics. She kept going on about some drug, how it hadn’t worked. She kept going on about someone called Ricky Scott. I put down the phone. Then, as it began to sink in, I called this person back. It was Anne, and ‘Ricky Scott’ was Dad. Apparently, he’d changed his name. Scott was his mother’s maiden name.

It was his alcoholism that had killed him. Of course, I drove straight down there, to the hospital. I felt fucking robotic. I was just going through the motions. That was the first time I had ever laid eyes on Anne. ‘Oh my God,’ she gasped. ‘You’re so like your father.’ All I remember is lots of people smoking, and drinking tea. I was asked if I wanted to see him – Dad. I said no.

‘I can’t believe you’re not going to see him,’ she said.

‘Well, that’s my choice,’ I said. I knew I wouldn’t be very good at seeing a dead person. It just wasn’t something I could put myself through. Years later, a close friend of mine died. I was asked to go and identify the body. But I couldn’t. I had to send someone else. I wasn’t any stronger then.

For all that I hated him, burying Dad was one of the worst days of my life. The funeral was horrible. She organised it, Anne, in a Margate crematorium so characterless it might as well have been a branch of Tesco. Oh, it was bad, really bad. We walked in, and his songs were playing, him singing. To me, that was the worst thing. And then, all these strangers…We knew no one.

Mum didn’t go, but my sisters did. And Ronnie, though not without a fight. By this time, Ronnie was a desperate heroin addict, and he was refusing to go. I was at my wits’ end. Finally, about an hour before the funeral, I gave him money so that he could buy what he needed to get him through. I thought it was better for him to be there and off his face, than not there at all. How low can you go? Very low indeed, if you’re desperate.

We carried Dad in, in his wooden box, and I could have cried. I started listening to the service, and they were calling him Ricky. That wasn’t even his name. His name’s Gordon, I thought. Why the fuck are they calling him Ricky? Then Anne turned round, and said: ‘I think your father would have wanted you to say a few words.’ So I did.

‘On behalf of the Ramsay family, I just want to say that we don’t know this “Ricky”. Dad’s name is Gordon.’ I got so upset I couldn’t even finish my sentence. I burst into tears. It took me several attempts to get the words out. Afterwards, we tried to be polite. We went and spent the requisite fifteen minutes at the knees-up that she’d organised. But I couldn’t have taken any more than that. Ronnie was out of it in any case. We could have been at a family christening for all he knew.

After that, I drove back to London and I went straight back to the kitchen. I was there, on the pass, working as hard as ever, trying not to think – or at least, to think only about the next order. I don’t think I’ve ever needed my kitchen so much in all my life.

What did my father leave me? A watch, actually. Everything else he ‘owned’ was on hire purchase anyway. He never tasted my cooking in the end, though even if he had, I doubt he would have been impressed. ‘Cooking is for poofs,’ he used to say. ‘Only poofs cook.’

But there is something else, too. Someone, I should say. Dad had another child, a girl, before he met Mum. Her parents adopted the baby. Apparently, Dad had planned on marrying her, but her parents had other ideas. One night, they went to see him sing, and then they followed him home and told him to stay away from their daughter. They threatened to beat him up. Perhaps his performance that evening had been even worse than usual. So that was that. He walked away, and went after Mum instead. My father’s parents knew all about this child, but they kept it from Mum, though she found out, of course – and several times, when she was expecting Diane, she even saw his child.

CHAPTER TWO FOOTBALL (#ulink_921262fe-c1c5-59d4-b025-0ee74d6b5800)

I MUST HAVE been about eight when I realised I was good at football. It was football, not cooking, that was my first real passion. I was a left-footed player – still am – and I was always in the back garden, or out in the close, kicking a ball against the wall. I used to long for Saturday mornings. The night before, I’d polish my boots until I got the most amazing shine on them. I remember my first pair of football boots. They were second-hand, bought from the Barras by Mum, and they didn’t fit properly; I had to wear two or three pairs of socks with them at first. But that didn’t matter to me, because owning them was more exciting than anything.

Football was one way I thought I could impress Dad. Nothing else worked. He never came into school, to see how we were doing, and he never thought our swimming was as good as his. But he and my Uncle Ronald were huge Rangers fans, and I could see that this might be a way to reach him. Uncle Ronald had a season ticket, and any time we went up to Glasgow, we would go off to Ibrox to see a game. I must have been about seven when I went to my first match. I remember being up on Ronald’s shoulders, and the incredible roar of the crowd. It was quite frightening. They still had the terraces in those days, and when the crowd celebrated, everyone surged forward: this great, heaving mass. I was always worried things might kick off, especially during derby matches. There was so much aggression between Rangers and Celtic and I could never understand why they had to be that nasty. My uncle told me that the men all worked together in the shipyard Monday to Friday but when it came to the weekend, they hated one another’s guts. I was very struck by that as a boy.

Back in Stratford, I was chosen to play under-14 football when I was just eleven, and, later, I used to be excused from rugby and athletics because I was representing the county at football; at twelve years old, I played for Warwickshire. So I had a fair idea that other people thought I was good, too. Did I enjoy it? Well, it was certainly better than rugby, which I hated. I was skinny, really skinny, and whenever we played rugby I just used to get mullered. And yes, of course I enjoyed it. I loved it. But if I am honest, it was also a good way of getting out of the house, especially at weekends. If Dad came to watch it was a special relief because at least that meant he wasn’t at home playing country and western, deafening all the neighbours, and giving Mum a hard time. He didn’t always come to watch, though. On those days, you’d come home and Dickie Davies would be on the telly, and while you desperately tried to watch the results, Dad would be busy trying to prove to you that he was a better guitarist than Hank Marvin. Sometimes, he didn’t even ask you the score, or whether or not you’d made any goals. I got used to it.

I had plenty of setbacks along the way, though, my progress was hardly meteoric. For one thing, we moved so often that I always had to secure a place in a new team. Then, when I was fourteen, I had the most terrible footballing accident. I was playing in a county match, in Leamington Spa. In the first two minutes of the game I went up to head a ball, and the miracle was that the ball went straight into the back of the net. Unfortunately, along the way, the goalkeeper had managed to punch me in the stomach and the combination of my exuberance and his mistaking the height of my jump meant that he somehow perforated my spleen. What a nightmare.

I went down and, at first, I thought I was only winded. The referee came over and sat me up and made me do all these sit-ups. I felt dizzy and weird. So he sent me off to get some water. I went to pee and suddenly I was peeing blood, and two minutes later I collapsed. An ambulance was called.

In the hospital, they didn’t know it was my spleen. First, they thought it was my appendix; then they thought it was a collapsed lung. That night, I was doubled over in pain. I was crippled with it and was crying my eyes out. The immense fucking agony, you would not have believed it. The doctors didn’t know what to do. Dad was away for some reason, in Texas, I think, and no one could get hold of Mum, so there was no one to sign the consent forms. In the end, they took me down to surgery anyway and somehow managed to repair the damage, though they took my appendix out as well, in the end. I was scared. I wanted Mum.

The operation really knocked me back. But there was worse to come. Two weeks later, an abscess developed internally. So it was back into hospital. This time, I had blood poisoning. All told, my recovery took three months from start to finish. I couldn’t do anything physical. I couldn’t run, I couldn’t jump and I couldn’t train. That was a terrible blow for a fourteen-year-old boy. And then when I started kicking the ball again, I was nervous about going into a tackle. I had lost my confidence.

If Dad had been there, at the hospital, if he’d understood how serious the situation had been, he might have been a bit more sympathetic. But he wasn’t. When he eventually came back, he announced that he’d managed to get some construction work in Amsterdam, and that he was going to take me with him while I convalesced. I was really excited, but only for one reason. I wanted to go and look at the Ajax stadium. The trouble was, it was only about ten weeks since the operation, I still wasn’t as well as I should have been, and Dad was hardly the kind of man to take care of me. For days, I was just left to wander round this stadium. We were in bed-and-breakfast accommodation, so he would go off to work (though that, predictably, lasted about three weeks), leaving me behind with four guilders to my name. You don’t realise it till later – that you’ve been abandoned. I think now: fuck, I was on my jack, wandering around, a fourteen-year-old boy who’s just had major surgery. It was fun, going to the Ajax stadium one, two, three times. But then – even the fucking gardeners got to know me. That was a very, very strange trip.

I had pictures of my heroes, Kenny Dalglish and Kevin Keegan, on my bedroom wall, but I never thought I’d be professional. Apart from anything, even after the accident, I still had terrible problems with my feet. I was cramming my feet into boots that were too small – the ethos of the day was to get boots that were a size too small. Even my coach told me to do that. Some Saturday nights, I’d sit on the side of the bath, wearing my boots, with my feet in hot water, trying to literally mould the leather around them. To this day, I’ve got toes that are bent at the end – hammer toes. By the time I’m an old man, they’ll be like claws. I never had the money for decent boots, even if they’d been the right size. I had to make them last and then, when they were finally worn out, when they looked like a few bits of old cardboard tied together with string, Mum had to secretly slip me money to buy a new pair.

When we moved down to Banbury, I began playing for Banbury United. I suppose that’s when I started getting noticed, though I was only paid my expenses because I was still at school. I played left back. Every term, players from our team were invited up to Oxford United, where they trained with the third or fourth team, and then played for the reserve side, which meant that they got to spend the most amazing week up there. I was picked up by coach and taken there – the first time that I’d been made to feel special, or any good at all, really. And then the travelling became more of a regular event – though I was crap at that. The coach used to make me feel so ill. A small bowl of porridge for breakfast and then, an hour later, I’d be sick as a dog. Hardly the hard man.

I remember my first serious game like it was yesterday. Dad was away and I couldn’t take Mum because, well, you don’t take your mum to football, do you? It was an English Schools competition, Oxfordshire County vs Inner London, and it was to be held at Loftus Road, the ground of Queens Park Rangers, in London. Amazing. A big, fucking stadium instead of the cow patch we had to play on in Banbury, and all the London players were from the youth teams of Chelsea, Tottenham and Arsenal. I thought we were going to get absolutely hammered – that the score would be 8-0 or something. These guys were bigger and stronger than us. But the funny thing was that we beat them 2-1. But it was a dirty game. I was taken off, fifteen minutes before the end of the second half, after a bad tackle to my knee. Another injury from which it took me ages to recover. Perhaps I was doomed when it came to football.

After I’d recovered, I played in an FA Cup youth game and it was there that a Rangers scout spotted me. They asked if I’d like to spend a week of my next summer holiday with the club. Fucking hell. I couldn’t believe it. It wasn’t just the fact that it was a professional club; it was RANGERS, the one that would really have an impact on the way Dad felt about me – or so I thought. The trouble was, Mum and Dad were going through a really shitty time then, and in a way, it put me under even more pressure. A part of me didn’t want anyone to know, just in case I couldn’t pull it off. I didn’t want to let anyone down and, in doing so, unwittingly make things even worse between them. By this point, I was sixteen and was pushing the upper age limit as far as breaking into professional football went. It was make-or-break time.

That first week was hard. I didn’t have a good time at all. I had an English accent, for one thing, so basically they just kicked the shit out of me for that. And they also made me use my right leg, which was fucking useless. We weren’t allowed to rely on only one foot, in much the same way as, in the kitchen, you must be able to chop with both hands. I’m naturally left-handed, but I can chop and peel with my right hand so if I cut myself, I’m okay – I’m prepared. Anyway, after that first week, I came back and I just hated Rangers. I hated the guts out of them. I had no problem with the training – I’ve never been afraid of hard work – but then, in the afternoons, after training, we had gone on to play snooker and eat for Britain. Food in Scotland was bad, then – unbelievably bad. It still is, in most cases. It was pie and gravy, pie and beans, or what the Scottish call a ‘slice’ – these big, square, processed slabs of sausage meat. Fucking hell. I didn’t have what you’d call a sophisticated palate, but I couldn’t stand it. And although I was in digs, with the other lads, I was very lonely. I wished I had a Scottish accent, something that would have made them feel more comfortable around me.

‘I was born in Johnstone, and Mum and Dad moved south,’ I kept trying to tell them. ‘But my gran and my uncle and aunt all live in Port Glasgow.’

They, of course, weren’t having any of it.

I suppose after that first week up there, I thought I’d really fucked it up. I was called back three times. The process was horrible, and I was in two minds about begging for a fucking contract out of Rangers. I was settled in Banbury in the flat with Diane and I’d started a foundation course in catering and it was going well, and there was this feeling, deep inside me, that something else was bubbling up. I was starting to get excited about food. Also, though Mum and Dad’s relationship was really going pear-shaped, they had moved back up to Scotland, and I was enjoying my freedom. I had my first serious girlfriend, I’d started working in a local hotel, I had a bit of money, and there was always Banbury United if I wanted football. I got about £15 a game. I wasn’t complaining. Still, I was just waiting for that call.

Mum phoned. She told me to contact my Uncle Ronald: he had some good news for me about Rangers. So that was what I did. ‘Look, things have moved on,’ he said. ‘I told you they were going to watch you, and they have, and they’re going to invite you back up.’

He gave me a number to call. It was for one of the head coaches. I couldn’t understand a word he was saying: he was speaking far, far too fast. But finally he said: ‘We want you back up. Can you bring your Dad to training on May seventeenth?’

I thought: oh, shit. At that point, I was barely speaking to Dad. I wasn’t even allowed to call the house. The trouble was that the first people the club want to talk to are your parents. They want to know that you’ve got security at home, that you’re properly supported. I was thinking: fuck, am I properly supported? No. I’m sixteen, and I’m living on my own, fending for myself. I rang Mum and asked her to tell him. I couldn’t face doing it myself.

So she did tell him and, all of a sudden he was…I don’t know. Not nice, exactly, but smarmy. He was excited now. I guess he had his eye on the main chance. He was going to live vicariously, through me. How did I feel about this? Wary and nervous. I knew he was drinking; I knew he’d been horrible to Mum; I knew what Yvonne had been through. The only thing that kept me going was the fact that Dad had promised to buy Mum a house – the first time he’d ever suggested such a thing. I hung on to that promise for dear life. I picked up on that one tiny moment, and managed to convince myself that he must have got his shit together at last. Still, it all felt so false – everyone pretending to be best mates, Dad and my uncle suddenly being so involved in my life. I had to live at home again, and take Dad to training with me every day. Being back there, I knew that things weren’t at all right. I felt it instantly. It was almost like Mum and Dad were staying together for the sake of my future at Rangers. I couldn’t bear that. It was pressure, massive pressure. It wasn’t as though I was in love with Dad and he had this amazing relationship with Mum, and all I had to do was concentrate and play football. I was worried. It was all so precarious – a house of cards that could tumble down around my ears at any moment.

This time, the training was going exceptionally well. I started playing in the testimonial games, and I was included on the first-team sheet, which was amazing. It was great, turning up to meet the bus when we were playing away from Ibrox, standing there waiting in your badge and tie, all spruced and immaculate as if you were off to a wedding. It was such a thrill. Outside the stadium, you’d be signing things like pillow cases and the side of prams, and families would turn up with their kids to have their trainers signed. Of course, they didn’t know me from Adam. They didn’t have a clue who I was. I was never a famous Rangers player because I was a member of the youth team. But, on the other hand, I was part of a squad that was doing well. The team has such a following that if you’re wearing the gear – you’re in, and that’s that.