По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

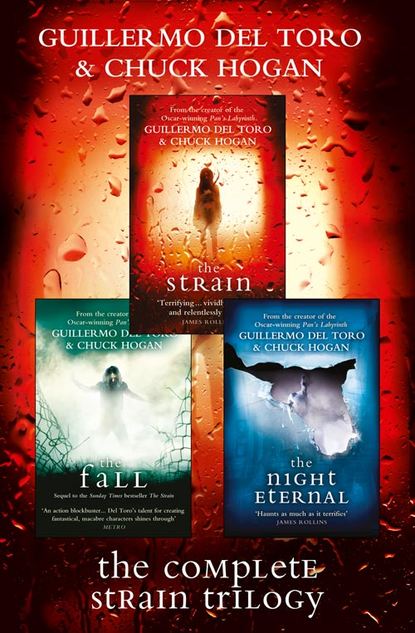

The Complete Strain Trilogy: The Strain, The Fall, The Night Eternal

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Barnes checked Nora, who nodded rigorously, with Eph on this all the way.

Director Barnes said, “The inference is that you believe this … this tumorous growth, this biological transformation … is somehow transmissible?”

“That is our supposition and our fear,” said Eph. “Jim may well be infected. We need to determine the progression of this syndrome, whatever it is, if we want to have any chance at all of arresting it and curing him.”

“Are you telling me you saw this … this retractable stinger, as you call it?”

“We both did.”

“And where is Captain Redfern now?”

“At the hospital.”

“His prognosis?”

Eph answered before Nora could. “Uncertain.”

Barnes looked at Eph, now starting to sense that something wasn’t kosher.

Eph said, “All we are requesting is an order to compel the others to receive medical treatment—”

“Quarantining three people means potentially panicking three hundred million others.” Barnes checked their faces again, as though for final confirmation. “Do you think this relates in any way to the disappearance of these bodies?”

“I don’t know,” said Eph. What he almost said was, I don’t want to know.

“Fine,” said Barnes. “I will start the process.”

“Start the process?”

“This will take some doing.”

Eph said, “We need this now. Right now.”

“Ephraim, what you have presented me with here is bizarre and unsettling, but it is apparently isolated. I know you are concerned for the health of a colleague, but securing a federal order of quarantine means that I have to request and receive an executive order from the president, and I don’t carry those around in my wallet. I don’t see any indication of a potential pandemic just yet, and so I must go through normal channels. Until that time, I do not want you harassing these other survivors.”

“Harassing?” said Eph.

“There will be enough panic without our overstepping our obligations. I might point out to you, if the other survivors have indeed become ill, why haven’t we heard from them by now?”

Eph had no answer.

“I will be in touch.”

Barnes went off to make his calls.

Nora looked at Eph. She said, “Don’t.”

“Don’t what?” She could see right through him.

“Don’t go looking up the other survivors. Don’t screw up our chance of saving Jim by pissing off this lawyer woman or scaring off the others.”

Eph was stewing when the outside doors opened. Two EMTs wheeled in an ambulance gurney with a body bag set on top, met by two morgue attendants. The dead wouldn’t wait for this mystery to play itself out. They would just keep coming. Eph foresaw what would happen to New York City in the grip of a true plague. Once the municipal resources were overwhelmed—police, fire, sanitation, morticians—the entire island, within weeks, would degenerate into a stinking pile of compost.

A morgue attendant unzipped the bag halfway—and then emitted an uncharacteristic gasp. He backed away from the table with his gloved hands dripping white, the opalescent fluid oozing from the black rubber bag, down the side of the stretcher, onto the floor.

“What the hell is this?” the attendant asked the EMTs, who stood by the doorway looking particularly disgusted.

“Traffic fatality,” said one, “following a fight. I don’t know … must have been a milk truck or something.”

Eph pulled gloves from the box on the counter and approached the bag, peering inside. “Where’s the head?”

“In there,” said the other EMT. “Somewhere.”

Eph saw that the corpse had been decapitated at the shoulders, the remaining mass of its neck splattered with gobs of white.

“And the guy was naked,” added the EMT. “Quite a night.”

Eph drew the zipper all the way down to the bottom seam. The headless corpse was overweight, male, roughly fifty. Then Eph noticed its feet.

He saw a wire wound around the bare big toe. As though there had been a casualty tag attached.

Nora saw the toe wire also, and blanched.

“A fight, you say?” said Eph.

“That’s what they told us,” said the EMT, opening the door to the outside. “Good day to you, and good luck.”

Eph zipped up the bag. He didn’t want anyone else seeing the tag wire. He didn’t want anyone asking him questions he couldn’t answer.

He turned to Nora. “The old man.”

Nora nodded. “He wanted us to destroy the corpses,” she remembered.

“He knew about the UV light.” Eph stripped off his latex gloves, thinking again of Jim, lying alone in isolation—with who could say what growing inside him. “We have to find out what else he knows.”

17th Precinct Headquarters, East Fifty-first Street, Manhattan

SETRAKIAN COUNTED thirteen other men inside the room-size cage with him, including one troubled soul with fresh scratches on his neck, squatting in the corner and rubbing spit vigorously into his hands.

Setrakian had seen worse than this, of course—much worse. On another continent, in another century, he had been imprisoned as a Romanian Jew in World War II, in the extermination camp known as Treblinka. He was nineteen when the camp was brought down in 1943, still a boy. Had he entered the camp at the age he was now, he would not have lasted a few days—perhaps not even the train ride there.

Setrakian looked at the Mexican youth on the bench next to him, the one he had first seen in booking, who was now roughly the same age Setrakian had been when the war ended. His cheek was an angry blue and dried black blood clogged the slice beneath his eye. But he appeared to be uninfected.

Setrakian was more concerned about the youth’s friend, lying on the bench next to him, curled up on his side, not moving.

For his part, Gus, feeling angry and sore, and jittery now that his adrenaline was gone, grew wary of the old man looking over at him. “Got a problem?”

Others in the tank perked up, drawn by the prospect of a fight between a Mexican gangbanger and an aged Jew.