По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

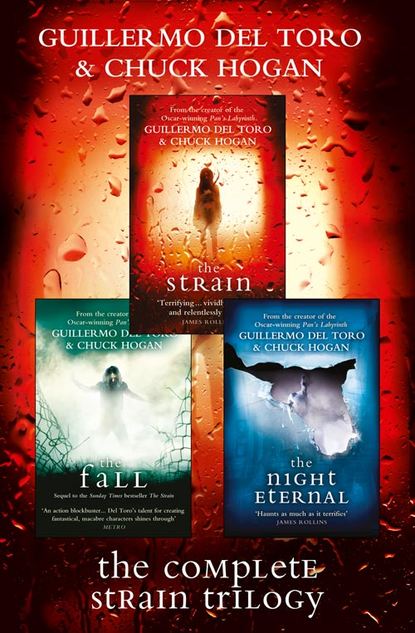

The Complete Strain Trilogy: The Strain, The Fall, The Night Eternal

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The Thing was an expert in horror, but this human horror indeed exceeded any other possible fate. Not only because it was without mercy, but because it was acted upon rationally and without compulsion. It was a choice. The killing was unrelated to the larger war, and served no purpose other than evil. Men chose to do this to other men and invented reasons and places and myths in order to satisfy their desire in a logical and methodical way.

As the Nazi officer mechanically shot each man in the back of the head and kicked them forward into the consuming pit, Abraham’s will eroded. He felt nausea, not at the smells or the sights but at the knowledge—the certainty—that God was no longer in his heart. Only this pit.

The young man wept at his failure and the failure of his faith as he felt the muzzle of the Luger press against the bare skin—

Another mouth at his neck—

And then he heard the shots. From across the yard, a work crew of prisoners had taken the observation towers and were now overriding the camp, shooting every uniformed officer in sight.

The man at his back went away. Leaving Setrakian poised at the edge of that pit.

A Pole next to him in line stood and started to run—and the will seeped back into young Setrakian’s body. Hands clutched to his chest, he found himself up and running, naked, toward the camouflaged barbed-wire fence.

Gunfire all around him. Guards and prisoners bursting with blood and falling. Smoke now, and not just from the pit: fires starting all across the camp. He made it to the fence, near some others and somehow, with anonymous hands lifting him to the top, doing what his broken hands could not, he fell to the other side.

He lay on the ground, rifle rounds and machine-gun fire ripping into the dirt around him—and again, helping hands and arms raised him up, lifting him to his feet. And as his unseen helpers were torn apart by bullets, Setrakian ran and ran and found himself crying … for in the absence of God he had found Man. Man killing man, man helping man, both of them anonymous: the scourge and the blessing.

A matter of choice.

For miles he ran, even as Austrian reinforcements closed in. His feet were sliced open, his toes shattered by rocks, but nothing could stop him now that he was beyond the fence. His mind was of a single purpose as he finally reached the woods and collapsed in the darkness, hiding in the night.

DAWN (#)

17th Precinct Headquarters, East Fifty-first Street, Manhattan (#)

Setrakian shifted his weight, trying to get comfortable on the bench against the wall inside the precinct house holding tank. He had waited in a glass-walled prebooking area all night, stuck with many of the same thieves, drunks, and perverts he was caged in with now. During the long wait, he had had sufficient time to consider the scene he had made outside the coroner’s office, and realized he had spoiled his best chance at reaching the federal disease control agency in the person of Dr. Goodweather.

Of course he had come off like a crazy old man. Maybe he was slipping. Going wobbly like a gyroscope at the end of its revolutions. Maybe the years of waiting for this moment, lived on that line between dread and hope, had taken their toll.

Part of getting old is checking oneself constantly. Keeping a good firm grip on the handrail. Making sure you’re still you.

No. He knew what he knew. The only thing wrong with him now was that he was being driven mad by desperation. Here he was, being held captive in a police station in Midtown Manhattan, while all around him …

Be smart, you old fool. Find a way out of here. You’ve worked your way out of far worse places than this.

He replayed the scene from the booking area in his mind. In the middle of his giving his name and address and having the charges of disturbing the peace and criminal trespass explained to him, and signing a property form for his walking stick (“It is of immense personal significance,” he had told the sergeant) and his heart pills, a Mexican youth of eighteen or nineteen was brought in, wrists handcuffed behind him. The youth had been roughed up, his face scratched, his shirt torn.

What caught Setrakian’s eye were the burn holes in his black pants and across his shirt.

“This is bullshit, man!” said the youth, arms pulled tight behind him, leaning back as he was pushed ahead by detectives. “That puto was crazy. Dude was loco, he was naked, running in the streets. Attacking people. He came at us!” The detectives dropped him, hard, into a chair. “You didn’t see him, man. That fucker bled white. He had this fucking … this thing in his mouth! It wasn’t fucking human!”

One of the detectives came over to Setrakian’s booking sergeant’s cubicle, wiping sweat off his face with a paper towel. “Crazy-ass Mex. Two-time juvie loser, just turned eighteen. Killed a man this time, in a fight. Him and a buddy, must have jumped the guy, stripped off his clothes. Tried to roll him right in the middle of Times Square.”

The booking sergeant rolled his eyes and continued pecking at his keyboard. He asked Setrakian another question, but Setrakian didn’t hear him. He barely felt the seat beneath him, or the warped fists his old, broken hands made. Panic nearly overtook him at the thought of facing the unfaceable again. He saw the future. He saw families torn apart, annihilation, an apocalypse of agonies. Darkness reigning over light. Hell on earth.

At that moment Setrakian felt like the oldest man on the planet.

Suddenly, his dark panic was supplanted by an equally dark impulse: revenge. A second chance. The resistance, the fight—the coming war—it had to begin with him.

Strigoi.

The plague had started.

Isolation Ward,

Jamaica Hospital Medical Center

JIM KENT, still in his street clothes, lying in the hospital bed, sputtered, “This is ridiculous. I feel fine.”

Eph and Nora stood on either side of the bed. “Let’s just call it a precaution, then,” said Eph.

“Nothing happened. He must have knocked me down as I went through the door. I think I blacked out for a minute. Maybe a low-grade concussion.”

Nora nodded. “It’s just that … you’re one of us, Jim. We want to make sure everything checks out.”

“But—why in isolation?”

“Why not?” Eph forced a smile. “We’re here already. And look—you’ve got an entire wing of the hospital to yourself. Best bargain in New York City.”

Jim’s smile showed that he wasn’t convinced. “All right,” he said finally. “But can I at least have my phone so I can feel like I’m contributing?”

Eph said, “I think we can arrange that. After a few tests.”

“And—please tell Sylvia I’m all right. She’s going to be panicked.”

“Right,” said Eph. “We’ll call her as soon as we get out of here.”

They left shaken, pausing before exiting the isolation unit. Nora said, “We have to tell him.”

“Tell him what?” said Eph, a little too sharply. “We have to find out what we’re dealing with first.”

Outside the unit, a woman with wiry hair pulled back under a wide headband stood up from the plastic chair she had pulled in from the lobby. Jim shared an apartment in the East Eighties with his girlfriend, Sylvia, a horoscope writer for the New York Post. She brought five cats to the relationship, and he brought one finch, making for a very tense household. “Can I go in?” said Sylvia.

“Sorry, Sylvia. Rules of the isolation wing—only medical personnel. But Jim said to tell you that he’s feeling fine.”

Sylvia gripped Eph’s arm. “What do you say?”

Eph said, tactfully, “He looks very healthy. We want to run some tests, just in case.”

“They said he passed out, he was a bit woozy. Why the isolation ward?”

“You know how we work, Sylvia. Rule out all the bad stuff. Go step by step.”

Sylvia looked to Nora for female reassurance.

Nora nodded and said, “We’ll get him back to you as soon as we can.”

Downstairs, in the hospital basement, Eph and Nora found an administrator waiting for them at the door to the morgue. “Dr. Goodweather, this is completely irregular. This door is never to be locked, and the hospital insists on being informed of what is going on—”