По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

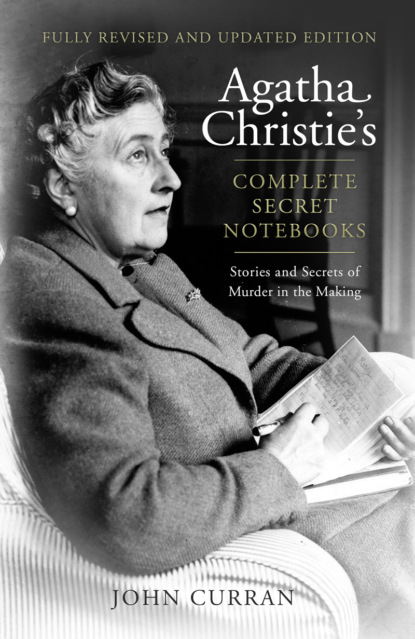

Agatha Christie’s Complete Secret Notebooks

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Act III Scene I The following evening

Assembled in library – George and Battle read code letter – Richmond – they wait – struggle in darkness. Lights go up – Antony holding Lemaitre – always suspected this fellow – colleague from the Surete

Act III That evening Battle and George

Virginia, Lord C, Bundle go to bed. Lights out – George and Battle – the cipher – George 3 – man in armour. They [struggle] – door opens – the window – shadows. Suddenly outbreak of activity – they roll over and over – the man in armour clangs down. Suddenly door opens – Lord C. switches on light – others behind him. Battle in front of window – Antony on top of Lemaitre – ‘I’ve got you.’

As the above extract might suggest, The Secret of Chimneys is, both as novel and play, a hugely enjoyable but preposterous romp; it is littered with loose ends, unlikely motivations and unconvincing characters. Suspects drop compromising notes; jewel thieves act with uncharacteristic homicidal responses; blackmail victims react with glee at a new ‘experience’ and bodies are disposed of with everyday nonchalance. And virtually nobody is who or what they seem. Why does Virginia not recognise Anthony if, as is reported in Chapters 15 and 24, she lived for two years in Herzoslovakia? Would someone really mistake a bundle of letters for the manuscript of a book? Would Battle accept Cade’s bona-fides so easily? It is difficult not to have a certain amount of sympathy with the pompous George Lomax and to sympathise deeply with the unfortunate Lord Caterham.

There are glimpses of the Christie to come in the final surprise revelation and the double-bluff with King Victor (in a novel about a disputed kingdom, why use this name for a character unconnected with the throne?), but her earlier thriller, The Man in the Brown Suit, and the later The Seven Dials Mystery, are, if not more credible, at least far less incredible.

The Mystery of the Blue Train (#ulink_6a8f9278-ccd0-5582-9229-0e500272dbf1)

29 March 1928

The elegant train is the setting for the murder of wealthy American Ruth Kettering. Fellow passenger Katherine Grey assists Hercule Poirot as he investigates the murder as well as the disappearance of the fabulous jewel, the Heart of Fire, among the wealthy inhabitants of the French Riviera.

The Mystery of the Blue Train was written at the lowest point in Christie’s life. In An Autobiography she writes, ‘Really, how that wretched book came to be written I don’t know.’ Following her disappearance and her subsequent separation from Archie Christie, she went to Tenerife with her daughter Rosalind and her secretary, Carlo Fisher, to finish the already started book, the writing of which also represented an important milestone. She now realised that her status had advanced from amateur to professional: ‘I was driven desperately on by the desire, indeed the necessity, to write another book and make money. [But] I had no joy in writing, no élan. I had worked out the plot – a conventional plot, partly adapted from one of my other stories … I have always hated The Mystery of the Blue Train but I got it written and sent it off to the publishers. It sold just as well as my last book had done. So I had to content myself with that – though I cannot say I have ever been proud of it.’

The short story to which she refers is ‘The Plymouth Express’, published in April 1923. A minor entry in the Poirot canon, it is doubtful that it merited expansion into a novel. Extra complications in the shape of the history of the Heart of Fire are added in the novel and the inclusion of a new character, Katherine Grey, is significant. Katherine lives in St Mary Mead, although she does not seem to know a certain Miss Jane Marple, who had made her detective debut some three months earlier in ‘The Tuesday Night Club’. A quiet, determined, sensible young woman seeing the world for the first time, Katherine is a sympathetic character who captivates Poirot.

Notes for The Mystery of the Blue Train are in two Notebooks: Notebook 1 has a mere five pages but Notebook 54 has over eighty, although the entries on each page are relatively short. They all reflect accurately the finished novel; no variations are considered, nor are there any discarded ideas, possibly because it was an expansion of a short story. Notes begin with Chapter 4 and then, twenty pages later, we find a listing of the earlier chapters, suggesting that those notes had been destroyed.

I include a dozen pages from towards the end of Notebook 54. They contain Poirot’s explanation of the crimes, a passage so close to the published version in Chapter 35 that it merits reproduction in full. Although the published version is more elaborate, nowhere else in the plotting of her books is there anything else like this. Flowing handwriting covers the pages, elucidating a complex plot with a minimum of deletion. Much of the following passage is almost exactly as Agatha Christie wrote it in Tenerife in 1927; I have added only punctuation. The single most concentrated example of continuous text in the Notebooks, it is an impressive example of Christie’s fluency, clarity and readability, all factors that play an important part in her continuing popularity.

‘Explanations? Mais oui, I will give them to you. It began with 1 point – the disfigured face, usually a question of identity; but not this time. The murdered woman was undoubtedly Ruth Kettering and I put it aside.’

‘When did you first begin to suspect the maid?’

‘I did not for some time – one trifling [point] – the note case – her mistress not on such terms as would make it likely – it awakened a doubt. She had only been with her mistress two months yet I could not connect her to the crime since she had been left behind in Paris. But once having a doubt I began to question that statement – how did we know? By the evidence of your secretary, Major Knighton, a completely outside and impartial testimony, and by the dead woman’s own confession testimony to the conductor. I put that latter point aside for the moment because a very curious idea was growing up in my mind. Instead, I concentrated on the first point – at first sight it seemed conclusive but it led me to consider Major Knighton and at once certain points occurred to me. To begin with he, also, had only been with you for a period of 2 months and his initial was also K. Supposing – just supposing – that it was his notecase. If Ada Mason and he were working together and she recognised it, would she not act precisely as she had done? At first taken aback, she quickly fell in with him gave herself time to think and then suggested a plausible explanation that fell in with the idea of DK’s guilt. That was not the original idea – the Comte de la Roche was to be the stalking horse – but after I had left the hotel she came to you and said she was quite convinced on thinking it over that the man was DK – why the sudden certainty? Clearly because she had had time to consult with someone and had received instructions – who could have given her these instructions? Major Knighton. And then came another slight incident – Knighton happened to mention that he has been at Lady Clanraven’s when there had been a jewel robbery there. That might mean nothing or on the other hand it might mean a great deal. And so the links of the chain –’

‘But I don’t understand. Who was the man in the train?’

‘There was no man – don’t you see the cleverness of it all? Whose words have we for it, that there was a man. Only Ada Mason’s – and we believe in Ada Mason because of Knighton’s testimony.’

‘And what Ruth said …’

‘I am coming to that – yes – Mrs. Kettering’s own testimony. But Mrs Kettering’s testimony is that of a dead woman, who cannot come forward to dispute it.’

‘You mean the conductor lied?’

‘Not knowingly – the woman who spoke to him he believed in all good faith to be Mrs Kettering.’

‘Do you mean that it wasn’t her?’

‘I mean that the woman who spoke to the conductor was the maid, dressed in her mistress’s clothes – wearing her very distinctive clothes remember – more noticeable than the woman herself – the little red hat jammed down over the eyes – the long mink coat – the bunch of auburn curls each side of the face. Do you not know, however, that it is a commonplace nowadays how like one woman is to another in her street clothes.’

‘But he must have noticed the change?’

‘Not necessarily, he saw The maid handed him the tickets – he hadn’t seen the mistress until he came to make up the bed. That was the first time he had a good look at her and that was the reason for disfiguring the face – he would probably have noticed that the dead woman was not the same as the woman he had talked to. M. Grey would The dining room attendants might have noticed and M. Grey of course would have, but by ordering a dinner basket that danger was avoided.’

‘Then – where was Ruth?’

P[oirot] paused a minute and then said very quietly ‘Mrs Kettering’s dead body was rolled up in the rug on the floor in the adjoining compartment.’

‘My God!’

‘It is easily understood. Major Knighton was in Paris – on your business. He boarded the train somewhere on its way round the ceinture – he spoke perhaps of bringing some message from you – then he draws her attention to something out of the window slips the cord round her neck and pulls … It is over in a minute. They roll up put the body in the adjoining compartment of which the door into the corridor is locked. Major Knighton hops off the train again – with the jewel case. Since the crime is not supposed to be committed until several hours later he is perfectly safe and his evidence and the supposed Mrs. Kettering’s words to the conductor will prove an alibi for her.

At the Gare de Lyon Ada Mason gets a dinner basket – then locks the door of her compartment – hurriedly changes into her mistress’s clothing – making up to resemble her and adjusting some false auburn curls – she is about the same height. Katherine Grey saw her standing looking out of her window later in the evening and would have been prepared to swear that she was still alive then. Before getting to Lyons, she arranges the body in the bunk, changes Her own into a man’s clothing and prepares to leave the train. It must have been then that When Derek Kettering enters his wife’s compartment the scene had been set and Ada Mason was in the other compartment waiting for the train to stop so as to leave the train unobserved – it is now drawn into Lyons – the conductor swings himself down – she follows, unobtrusively however, to proceed by slouching inelegantly along as though just taking the air but in reality she crosses over and takes the first train back to Paris where she establishes herself at the Ritz. Her name has been entered registered as booking a room the night before by one of Knighton’s female accomplices; she has only to wait for Mr. Van Aldin’s arrival. The jewels are in Knighton’s possession – not hers – and he disposes of them to Mr Papapolous

in Nice as arranged beforehand, entrusting them to her care only at the last minute to deliver to the Greek. All the same she made one little slip …’

‘When did you first connect Knighton with the Marquis?’

‘I had a hint from Mr Papapolous and I collected certain information from Scotland Yard – I applied it to Knighton and it fitted. He spoke French like a Frenchman; he had been in America and France and England at roughly the same times as the Marquis was operating. He had been last heard of doing jewel robberies in Switzerland and it was in Switzerland that you first met Major K. The Marquis was famous for his charm of manner [which he used] to induce you to offer him the post of secretary. It was at that time that rumours were going round about your purchase of the rubies – the Marquis meant to have these rubies. In seeing that you had given them to your daughter he installed his accomplice as her maid. It was a wonderful plan yet like great men he has his weakness – he fell genuinely in love with Miss Grey. It was that which made him so desirous of shifting the crime from Mr Comte de la Roche to Derek Kettering when the opportunity presented itself. And Miss Grey suspected the truth. She is not a fanciful woman by any means but she declares that she distinctly felt your daughter’s presence beside her one day at the Casino; she says she was convinced that the dead woman was trying to tell her something. Knighton had just left her – and it was gradually [borne in on her] what Mrs Kettering had been trying to convey to her – that Knighton was the man who had murdered her. The idea seemed so fantastic at the time that Miss Grey spoke of it to no one. But she acted on the assumption that it was true – she did not discourage Knighton’s advances, and she pretended to him that she believed in Derek Kettering’s guilt …

‘There was one thing that was a shocking blow. Major Knighton had a distinct limp, the result of a wound – the Marquis had no such limp – that was a stumbling block. Then Miss Tamplin mentioned one day that it had been a great surprise to the doctors that he should limp – that suggested camouflage. When I was in London I went to the surgeon who had looked after been in charge at Lady Tamplin’s Hospital and I got various technical details from him which confirmed my assumption. Then I met Miss Grey and found that she had been working towards the same end as myself. She had the cuttings to add – one a cutting of a jewel robbery at Lady Tamplin’s Hospital, another link in the chain of probability and also that when she was out walking with Major Knighton at St. Mary Mead, he was so much off his guard that he forgot to limp – it was only a momentary lapse but she noted it. She had suspicion that I was on the same track when I wrote to her from the Ritz. I had some trouble in my inquiries there but in the end I got what I wanted – evidence that Ada Mason actually arrived on the morning after the crime.’

My Favourite Stories and ‘The Man Who Knew’ (#ulink_67b5e453-2e93-5b6a-b6de-7294ed4d0d26)

‘Looking back over the past, I become increasingly sure of one thing. My tastes have remained fundamentally the same.’

An Autobiography

What were Agatha Christie’s own personal favourites of her output? In February 1972, in reply to a Japanese reader, she listed, with brief comments, her favourite books. But she makes an important point when she writes that her list of favourites would ‘vary from time to time, as every now and then I re-read an early book … and then I alter my opinion, sometimes thinking that it is much better than I thought it was – or nor as good as I had thought’. Although the choices are numbered it is not clear if they are in order of preference; she adds brief comments and reiterates her earlier point at the outset:

At the moment my own list would possibly be:

And Then There Were None – ‘a difficult technique which was a challenge …’

The Murder of Roger Ackroyd – ‘a general favourite …’

A Murder is Announced – ‘all the characters interesting …’

Murder on the Orient Express – ‘… it was a new idea for a plot.’

The Thirteen Problems – ‘a good series of short stories.’

Towards Zero – ‘… interesting idea of people from different places coming towards a murder instead of starting with the murder and working from that.’

Endless Night – ‘my own favourite at present.’

Crooked House – ‘… a study of a certain family interesting to explore.’

Ordeal by Innocence – ‘an idea I had for some time before starting to work upon it.’

The Moving Finger – ‘re-read lately and enjoyed reading it again, very much.’