По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

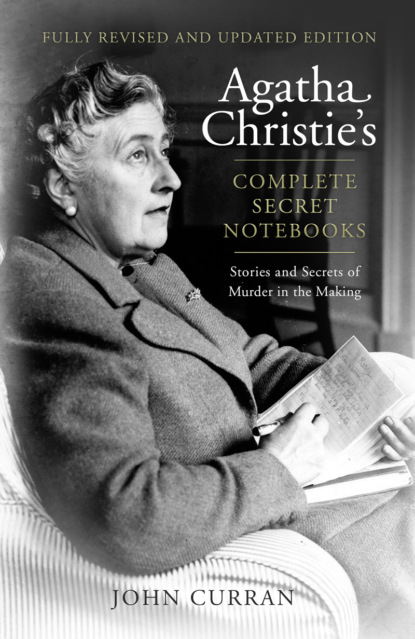

Agatha Christie’s Complete Secret Notebooks

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘We congratulate you on your acumen. The case is becoming much clearer. The drugged cocoa, taken on top of the poisoned coffee, amply accounts for the delay which puzzled the doctor.’

‘Exactly, Mr Le Juge. Although you have made one little error; the coffee, to the best of my belief was not poisoned.’

‘What proof have you of that?’

‘None whatever. But I can prove this – that poisoned or not, Mrs Inglethorp never drank it.’

‘Explain yourself.’

‘You remember that I referred to a brown stain on the carpet near the window? It remained in my mind, that stain, for it was still damp. Something had been spilt there, therefore, not more than twelve hours ago. Moreover there was a distinct odour of coffee clinging to the nap of the carpet and I found there two long splinters of china. I later reconstructed what had happened perfectly, for, not two minutes before I had laid down my small despatch case on the little table by the window and, the top of the table being loose, the case had been toppled off onto the floor onto the exact spot where the stain was. This, then, was what had happened. Mrs Inglethorp, on coming up to bed had laid her untasted coffee down on the table – the table had tipped up and [precipitated] the coffee onto the floor – spilling it and smashing the cup. What had Mrs Inglethorp done? She had picked up the pieces and laid them on the table beside her bed and, feeling in need of a stimulant of some kind, had heated up her cocoa

and drank it off before going to bed. Now, I was in a dilemma. The cocoa contained no strychnine. The coffee had not been drunk. Yet Mrs Inglethorp had been poisoned and the poison must have been administered sometime between the hours of seven and nine. But what else had Mrs Inglethorp taken which would have effectively masked the taste of the poison?’

‘Nothing.’

‘Yes – Mr Le Juge – she had taken her medicine.’

‘Her medicine – but …’

‘One moment – the medicine, by a [coincidence] already contained strychnine and had a bitter taste in consequence. The poison might have been introduced into the medicine. But I had my reasons for believing that it was done another way. I will recall to your memory that I also discovered a box which had at one time contained bromide powders. Also, if you will permit it, I will read out to you an extract – marked in pencil – out of a book on dispensing which I noticed at the dispensary of the Red Cross Hospital at Tadminster. The following is the extract …’

‘But, surely a bromide was not prescribed with the tonic?’

‘No, Mr Le Juge. But you will recall that I mentioned an empty box of bromide powders. One of the powders introduced into the full bottle of medicine would effectively precipitate the strychnine and cause it to be taken in the last dose. You may observe that the “Shake the bottle” label always found on bottles containing poison has been removed. Now, the person who usually poured out the medicine was extremely careful to leave the sediment at the bottom undisturbed.’

A fresh buzz of excitement broke out and was sternly silenced by the judge.

‘I can produce a rather important piece of evidence in support of that contention, because on reviewing the case, I came to the conclusion

that the murder had been intended to take place the night before. For in the natural course of events Mrs I[nglethorp] would have taken the last dose on the previous evening but, being in a hurry to see to the Fashion Fete she was arranging, she omitted to do so. The following day she went out to luncheon, so that she took the actual last dose 24 hours later than had been anticipated by the murderer. As a proof that it was expected the night before, I will mention that the bell in Mrs Inglethorp’s room was found cut on Monday evening, this being when Miss Paton was spending the night with friends. Consequently Mrs Inglethorp would be quite cut off from the rest of the house and would have been unable to arouse them, thereby making sure that medical aid would not reach her until too late.’

Notebook 37 showing the end of the deleted chapter from The Mysterious Affair at Styles. See here (#litres_trial_promo).

‘Ingenious theory – but have you no proof?’

Poirot smiled curiously.

‘Yes, Mr Le Juge – I have a proof. I admit that up to some hours ago, I merely knew what I have just said, without being able to prove it. But in the last few hours I have obtained a sure and certain proof, the missing link in the chain, a link in the murderer’s own hand, the one slip he made. You will remember the slip of paper held in Mrs Inglethorp’s hand? That slip of paper has been found. For on the morning of the tragedy the murderer entered the dead woman’s room and forced the lock of the despatch case. Its importance can be guessed at from the immense risks the murderer took. There was one risk he did not take – and that was the risk of keeping it on his own person – he had no time or opportunity to destroy it. There was only one thing left for him to do.’

‘What was that?’

‘To hide it. He did hide it and so cleverly that, though I have searched for two months it is not until today that I found it. Voila, ici le prize.’

With a flourish Poirot drew out three long slips of paper.

‘It has been torn – but it can easily be pieced together. It is a complete and damning proof.

Had it been a little clearer in its terms it is possible that Mrs Inglethorp would not have died. But as it was, while opening her eyes to who, it left her in the dark as to how. Read it, Mr Le Juge. For it is an unfinished letter from the murderer, Alfred Inglethorp, to his lover and accomplice, Evelyn Howard.’

And there, like Alfred Inglethorp’s pieced-together letter at the end of Chapter 12, Notebook 37 breaks off, despite the fact that the following pages are blank. We know from the published version that Alfred Inglethorp and Evelyn Howard are subsequently arrested for the murder, John and Mary Cavendish are reconciled, Cynthia and Lawrence announce their engagement, while Dr Bauerstein is shown to be more interested in spying than in poisoning. The book closes with Poirot’s hope that this investigation will not be his last with ‘mon ami’ Hastings.

The reviews on publication were as enthusiastic as the pre-publication reports for John Lane. The Times called it ‘a brilliant story’ and the Sunday Times found it ‘very well contrived’. The Daily News considered it ‘a skilful tale and a talented first book’, while the Evening News thought it ‘a wonderful triumph’ and described Christie as ‘a distinguished addition to the list of writers in this [genre]’. ‘Well written, well proportioned and full of surprises’ was the verdict of The British Weekly.

Poirot’s dramatic evidence in the course of the trial resembles a similar scene at the denouement of Leroux’s The Mystery of the Yellow Room (1907) – specifically mentioned in An Autobiography – where the detective, Rouletabille, gives his remarkable and conclusive evidence from the witness box. Had John Lane but known it, in demanding the alteration to the denouement of the novel he unwittingly paved the way for a half century of drawing-room elucidations stage-managed by both Poirot and Miss Marple. And although this explanation, in both courtroom and drawing room, is essentially the same, the unlikelihood of a witness being allowed to give evidence in this manner is self-evident. In other ways also The Mysterious Affair at Styles presaged what was to become typical Christie territory – an extended family, a country house, a poisoning drama, a twisting plot, and a dramatic and unexpected final revelation.

It is not a very extended family, however. Of Mrs Inglethorp’s family, there is a husband, two stepsons, one daughter-in-law, a family friend, a companion and a visiting doctor; there is the usual domestic staff although none of them is ever a serious consideration as a suspect. In other words, there are only seven suspects, which makes the disclosure of a surprise murderer more difficult. This very limited circle makes Christie’s achievement in a debut detective novel even more impressive. The clichéd view of Christie is that all of her novels are set in country houses and/or country villages. Statistically, this is inaccurate, as fewer than thirty (i.e. little over a third) of her books are set in such surroundings. And as Christie herself said, you have to set a book where people live.

Some ideas that feature in The Mysterious Affair at Styles would appear again throughout Christie’s career. The dying Emily Inglethorp calls out the name of her husband, ‘Alfred … Alfred’, before she finally succumbs. Is the use of his name an accusation, an invocation, a plea, a farewell; or is it entirely meaningless? Similar situations occur in several novels over the next 30 years. One novel, Why Didn’t They Ask Evans?, is built entirely around the dying words of the man found at the foot of the cliffs. In Death Comes as the End, the dying Satipy calls the name of the earlier victim, ‘Nofret’; as John Christow lies dying at the edge of the Angkatells’ swimming pool, in The Hollow, he calls out the name of his lover, ‘Henrietta.’ An extended version of the idea is found in A Murder is Announced when the last words of the soon-to-be-murdered Amy Murgatroyd, ‘she wasn’t there’, contain a vital clue. In both Murder in Mesopotamia – ‘the window’ – and Ordeal by Innocence – ‘the cup was empty’ and ‘the dove on the mast’ – dying words indicate the method of murder. And the agent Carmichael utters the enigmatic ‘Lucifer … Basrah’ before he expires in Victoria’s room in They Came to Baghdad.

The idea of a character looking over a shoulder and seeing someone or something significant makes its first appearance in Christie’s work when Lawrence looks horrified at something he notices in Mrs Inglethorp’s room on the night of her death. The alert reader should be able to tell what it is. This ploy is a Christie favourite and she enjoyed ringing the changes on the possible explanations. She predicated at least two novels – The Mirror Crack’d from Side to Side and A Caribbean Mystery – almost entirely on this, and it makes noteworthy appearances in The Man in the Brown Suit, Appointment with Death and Death Comes as the End, as well as a handful of short stories.

In the 1930 stage play Black Coffee – whose original title was to have been After Dinner – the only original script to feature Hercule Poirot, the hiding-place of the papers containing the missing formula is the same as the one devised by Alfred Inglethorp. And in an exchange very reminiscent of a similar one in The Mysterious Affair at Styles, it is a chance remark by Hastings that leads Poirot to this realisation.

In common with many crime stories of the period there are two floor-plans and no less than three reproductions of handwriting, all with a part to play in the eventual solution. And here also we see for the first time Poirot’s remedy for steadying his nerves and encouraging precision in thought: the building of card-houses. At crucial points in both Lord Edgware Dies and Three Act Tragedy he adopts a similar strategy, each time with equally triumphant results. The important argument overheard by Mary Cavendish through an open window in Chapter 6 foreshadows a similar and equally important case of eavesdropping in Five Little Pigs.

In his 1953 survey of detective fiction, Blood in their Ink, Sutherland Scott describes The Mysterious Affair at Styles as ‘one of the finest “firsts” ever written’. Countless Christie readers over almost a century would enthusiastically agree.

The Man in the Brown Suit (#ulink_c66aaffb-f9f6-59ac-9975-080a63399e74)

22 August 1924

When she is suddenly orphaned, Anne Beddingfeld

comes to London where she witnesses a suspicious death in a Tube station. A further death in the deserted Mill House convinces Anne to investigate and she boards a ship bound for South Africa, where she becomes involved in a breathless adventure.

Christie’s fourth novel drew extensively on her experiences with her first husband Archie when they both travelled the world in 1922. Although it starts in England, much of the novel is set on a ship travelling to South Africa and the climax of the novel takes place in Johannesburg. It is not a detective story but includes a whodunit element in tandem with murder, stolen jewels, a master criminal, mysterious messages and a shoot-out. It is an apprentice work before Christie found her true profession as a detective novelist and is hugely enjoyable, complete with a surprise solution which presages by two years her most stunning conjuring trick. And it also adopts the technique of using more than one narrator, a format that appears, in various guises, throughout her career in novels as diverse as The ABC Murders, Five Little Pigs and The Pale Horse.

The real-life Major Belcher, who employed Archie Christie as a business manager for the round-the-world trip, convinced Agatha Christie to include him as a character in her next novel. And he was not satisfied to be just any character; he wanted to be the murderer, whom he considered the most interesting character in any crime novel. He even suggested a title, Mystery at Mill House, the name of his own house. In An Autobiography Christie admits that although she did create a Sir Eustace Pedler, using some of Belcher’s characteristics, he was not actually the Major.

This unpublished photograph, from her 1922 world tour with Archie, shows Agatha Christie buying a wooden giraffe beside a train, exactly as her heroine, Anne, does in Chapter 23 of The Man in the Brown Suit.

She also relates in An Autobiography that when the serial rights of The Man in the Brown Suit were sold to the Evening News they changed the title to Anne the Adventuress. She thought this ‘as silly a title as I had ever heard’ – although the first page of Notebook 34 is headed ‘Adventurous Anne’.

The accuracy of the dozen pages in Notebook 34 suggests earlier, rougher notes, but as Christie wrote much of this book in South Africa it is understandable that they no longer exist.

Chapter I – Anne – her life with Papa – his friends … his death – A left penniless … interview with lawyer left with £95.

Chapter II – Accident in Tube – The Man in the Tube – Anne comes home.

Announcement in paper ‘Information Wanted’ solicitor from Scotland Yard – Inspector coming to interview Anne – her calmness – Brachycephalic – not a doctor. Suggest about being a detective – takes out piece of paper – smells mothballs – realises paper was taken from dead man 17 1 22

III – Visit to Editor (Lord Northcliffe) – takes influential card from hall – her reception – if she makes good. The order to view – Does she find something? Perhaps a roll of films?

[There is no IV in the notebook]

V – Walkendale Castle – her researches – The Arundel Castle – Anne makes her passage

VI – Major Sir Eustace Puffin [Pedler] – changing cabins – 13 – to – 17 – general fuss – Eustace, Anne and Dr Phillips and Pratt all laying claim to it