По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

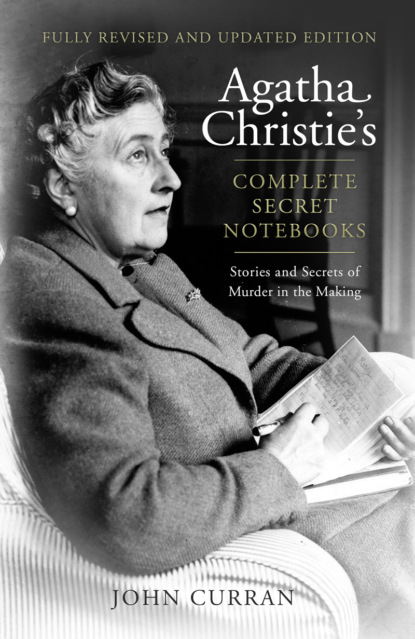

Agatha Christie’s Complete Secret Notebooks

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘I disagree with that most utterly.’

‘You consider the fragment important?’

‘Of the first importance.’

‘But I believe,’ interposed the judge, ‘that no-one in the house had a green garment in their possession.’

‘I believe so, Mr Le Juge,’ agreed Poirot facing in his direction. ‘And so at first, I confess, that disconcerted me – until I hit upon the explanation.’

Everybody was listening eagerly.

‘What is your explanation?’

‘That fragment of green was torn from the sleeve of a member of the household.’

‘But no-one had a green dress.’

‘No, Mr Le Juge, this fragment is a fragment torn from a green land armlet.’

With a frown the judge turned to Sir Ernest.

‘Did anyone in that house wear an armlet?’

‘Yes, my lord. Mrs Cavendish, the prisoner’s wife.’

There was a sudden exclamation and the judge commented sharply that unless there was absolute silence he would have the court cleared. He then leaned forward to the witness.

‘Am I to understand that you allege Mrs Cavendish to have entered the room?’

‘Yes, Mr Le Juge.’

‘But the door was bolted on the inside.’

‘Pardon, Mr Le Juge, we have only one person’s word for that – that of Mrs Cavendish herself. You will remember that it was Mrs Cavendish who had tried that door and found it locked.’

‘Was not her door locked when you examined the room?’

‘Yes, but during the afternoon she would have had ample opportunity to draw the bolt.’

‘But Mr Lawrence Cavendish has claimed that he saw it.’

There was a momentary hesitation on Poirot’s part before he replied.

‘Mr. Lawrence Cavendish was mistaken.’

Poirot continued calmly:

‘I found, on the floor, a large splash of candle grease, which upon questioning the servants, I found had not been there the day before. The presence of the candle grease on the floor, the fact that the door opened quite noiselessly (a proof that it had recently been oiled) and the fragment of the green armlet in the door led me at once to the conclusion that the room had been entered through that door and that Mrs Cavendish was the person who had done so. Moreover, at the inquest Mrs Cavendish declared that she had heard the fall of the table in her own room. I took an early opportunity of testing that statement by stationing my friend Mr Hastings

in the left wing just outside Mrs Cavendish’s door. I myself, in company with the police, went to [the] deceased’s room and whilst there I, apparently accidentally, knocked over the table in question but found, as I had suspected, that [it made] no sound at all. This confirmed my view that Mrs Cavendish was not speaking the truth when she declared that she had been in her room at the time of the tragedy. In fact, I was more than ever convinced that, far from being in her own room, Mrs Cavendish was actually in the deceased’s room when the table fell. I found that no one had actually seen her leave her room. The first that anyone could tell me was that she was in Miss Paton’s room shaking her awake. Everyone presumed that she had come from her own room – but I can find no one who saw her do so.’

The judge was much interested. ‘I understand. Then your explanation is that it was Mrs Cavendish and not the prisoner who destroyed the will.’

Poirot shook his head.

‘No,’ he said quickly, ‘That was not the reason for Mrs Cavendish’s presence. There is only one person who could have destroyed the will.’

‘And that is?’

‘Mrs Inglethorp herself.’

‘What? The will she had made that very afternoon?’

‘Yes – it must have been her. Because by no other means can you account for the fact that on the hottest day of the year [Mrs Inglethorp] ordered a fire to be lighted in her room.’

The judge objected. ‘She was feeling ill …’

‘Mr Le Juge, the temperature that day was 86 in the shade. There was only one reason for which Mrs Inglethorp could want a fire – namely to destroy some document. You will remember that in consequence of the war economies practised at Styles, no waste paper was thrown away and that the kitchen fire was allowed to go out after lunch. There was, consequently, no means at hand for the destroying of bulky documents such as a will. This confirms to me at once that there was some paper which Mrs Inglethorp was anxious to destroy and it must necessarily be of a bulk which made it difficult to destroy by merely setting a match to it. The idea of a will had occurred to me before I set foot in the house, so papers burned in the grate did not surprise me. I did not, of course, at that time know that the will in question had only been made the previous afternoon and I will admit that when I learnt this fact, I fell into a grievous error. I deduced that Mrs Inglethorp’s determination to destroy this will came as a direct consequence of the quarrel and that consequently the quarrel took place, contrary to belief, after the making of the will.

‘When, however, I was forced to reluctantly abandon this hypothesis – since the various interviews were absolutely steady on the question of time – I was obliged to cast around for another. And I found it in the form of the letter which Dorcas describes her mistress as holding in her hand. Also you will notice the difference of attitude. At 3.30 Dorcas overhears her mistress saying angrily that “scandal will not deter her.” “You have brought it on yourself” were her words. But at 4.30, when Dorcas brings in the tea, although the actual words she used were almost the same, the meaning is quite different. Mrs Inglethorp is now in a clearly distressed condition. She is wondering what to do. She speaks with dread of the scandal and publicity. Her outlook is quite different. We can only explain this psychologically by presuming [that] her first sentiments applied to the scandal between John Cavendish and his wife and did not in any way touch herself – but that in the second case the scandal affected herself.

‘This, then, is the position: At 3.30 she quarrels with her son and threatens to denounce him to his wife who, although they neither of them realise it, overhears part of the conversation. At 4 o’clock, in consequence of a conversation at lunch time on the making of wills by marriage, Mrs Inglethorp makes a will in favour of her husband, witnessed by her gardener. At 4.30 Dorcas finds her mistress in a terrible state, a slip of paper in her hand. And she then orders the fire in her room to be lighted in order that she can destroy the will she only made half an hour ago. Later she writes to Mr Wells, her lawyer, asking him to call on her tomorrow as she has some important business to transact.

Now what occurred between 4 o’clock and 4.30

to cause such a complete revolution of sentiments? As far as we know, she was quite alone during the time. Nobody entered or left the boudoir. What happened then? One can only guess but I have an idea that my guess is fairly correct.

‘Late in the evening Mrs Inglethorp asked Dorcas for some stamps and my thinking is this. Finding she had no stamps in her desk she went along to that of her husband which stood at the opposite corner. The desk was locked but one of the keys on her bunch fitted it. She accordingly opened the desk and searched for stamps – it was then she found the slip of paper which wreaked such havoc! On the other hand Mrs Cavendish believed that the slip of paper to which her mother [in-law] clung so tenaciously was a written proof of her husband’s infidelity. She demanded it. These were Mrs Inglethorp’s words in reply:

‘“No, [it is out of the] question.” We know that she was speaking the truth. Mrs Cavendish however, believed she was merely shielding her step-son. She is a very resolute woman and she was wildly jealous of her husband and she determined to get hold of that paper at all costs and made her plans accordingly. She had chanced to find the key of Mrs Inglethorp’s dispatch case which had been lost that morning. She had meant to return it but it had probably slipped her memory. Now, however, she deliberately retained it since she knew Mrs Inglethorp kept all important papers in that particular case. Therefore, rising about 4 o’clock she made her way through Miss Paton’s room, which she had previously unlocked on the other side.’

‘But Miss Paton would surely have been awakened by anyone passing through her room.’

‘Not if she were drugged.’

‘Drugged?’

‘Yes – for Miss Paton to have slept through all the turmoil in that next room was incredible. Two things were possible: either she was lying (which I did not believe) or her sleep was not a natural one. With this idea in view I examined all the coffee cups most carefully, taking a sample from each and analysing. But, to my disappointment, they yielded no result. Six persons had taken coffee and six cups were found. But I had been guilty of a very grave oversight. I had overlooked the fact that Dr Bauerstein had been there that night. That changed the face of the whole affair. Seven, not six people had taken coffee. There was, then, a cup missing. The servants would not observe this since it was the housemaid Annie who had taken the coffee tray in and she had brought in seven cups, unaware that Mr Inglethorp never took coffee. Dorcas who cleared them away found five cups and she suspected the sixth [of] being Mrs Inglethorp’s. One cup, then, had disappeared and it was Mademoiselle Cynthia’s, I knew, because she did not take sugar in her coffee, whereas all the others did and the cups I had found had all contained sugar. My attention was attracted by the maid Annie’s story about some “salt” on the cocoa tray which she took nightly into Mrs Inglethorp’s room. I accordingly took a sample of that cocoa and sent it to be analysed.’

‘But,’ objected the judge, ‘this has already been done by Dr Bauerstein – with a negative result – and the analysis reported no strychnine present.’

‘There was no strychnine present. The analysts were simply asked to report whether the contents showed if there were or were not strychnine present and they reported accordingly. But I had it tested for a narcotic.’

‘For a narcotic?’

‘Yes, Mr Le Juge. You will remember that Dr Bauerstein was unable to account for the delay before the symptoms manifested themselves. But a narcotic, taken with strychnine, will delay the symptoms some hours. Here is the analyst’s report proving beyond a doubt that a narcotic was present.’

The report was handed to the judge who read it with great interest and it was then passed on to the jury.