По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

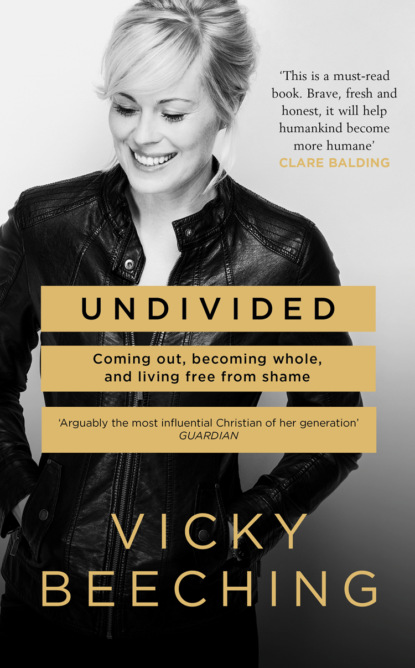

Undivided: Coming Out, Becoming Whole, and Living Free From Shame

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“You mean not eating?” I replied, sounding worried.

“Yes,” he said. “You know Jesus fasted for forty days, like the Gospels tell us. It’s a proven way to get free from demons that won’t go any other way. If you want God’s freedom enough that you’re willing to fast from food, you’ll see your feelings change for sure.”

I walked away, clutching the tissues. The auditorium was empty; they had prayed with me long after the meeting had ended. The band had stopped playing, and all the other youth had left the venue. I walked through the huge empty building, weaving my way through the rows of chairs and out into the night.

Rather than finding freedom, healing, and pastoral support from those adults, I came away feeling more ashamed and broken. Previously, I’d thought of my feeling for girls as emotional, biological, and psychological. But now panic set in: apparently I was not creating these desires myself—it was the sinister work of demons. This information, new to me, was extremely alarming.

I thought about the man’s encouragement to fast too. I decided that, yes, I would go to any lengths to get free from my sinful desires, even if it meant starving myself. Food, body image, and self-worth are tricky for any young adult, and this set in motion a preference for punishing my body rather than caring for it.

My mind felt full to the brim. The hope I’d felt surging through me that evening as I’d listened to the red-haired girl and her testimony had fallen flat. That night, I fell asleep under the canvas of my tent, scared stiff that I was inhabited by dark powers that would never let me go.

I took what my Christian leaders had taught me at face value, and I didn’t feel equipped to question it. I was an intelligent person, near the top of my class in most school subjects, but when it came to spirituality, I wasn’t used to thinking for myself. There were no LGBTQ+ people in my life, so I didn’t have role models to tell me that same-sex feelings were, in fact, not the work of demons or that being gay and Christian was possible.

I’d summoned all my teenage courage that night and spoken out about my same-sex feelings, asking for help. Having had it go so badly, I couldn’t imagine telling another soul about my secret ever again. As the writer Ian McEwan strikingly expresses in his novel Atonement: “A person is, among all else, a material thing, easily torn, not easily mended.” After that night at summer camp, I would not be easily mended.

6 (#ulink_f2ca6e5a-1cc0-511d-8cbf-db533d0a2f6e)

“This,” he said, gesturing soberly, “is what happens when you have … sex.” Looking at us with an intense gaze, the man at the front of the Christian youth event held up two pieces of white paper. He took a stick of glue and spread it liberally over both sheets. Then he pressed the sheets together, so they stuck firmly.

“Sex means you are literally gluing your soul to the other person; it’s sacred. Something significant happens when two people become ‘one flesh,’ as the Bible describes it. It’s not just about flesh and bone; part of you joins with that other person. It’s a spiritual union that cannot be broken.” He held the two pieces of paper in the air, showing us they were completely glued together.

“Now, see what happens if you have sex with someone casually—who you’re not married to—and then you break up.” His brow furrowed as he took the two pieces of paper and, starting at the top, tried to pull them apart. Of course, the glue had done its work, and this proved a difficult thing to attempt. Finally, he managed to separate them but was left with a mess: part of one piece of paper was left attached to the other and vice versa. In his hands the two sheets—once perfect—were now ripped to shreds and full of holes.

“This,” he said, “is what sex outside of marriage does to your body and soul. You leave a part of yourself with that other person. You are both damaged by it. And you can never be whole again.” All of us in that summer camp seminar were around the age of sixteen, and we exchanged worried glances.

“Save sex for marriage,” he said, bringing his illustration to a close. “Wait for the partner God has chosen for you, the perfect husband or wife, who you’ll be married to for life. If you don’t wait, the consequences are very serious in God’s eyes.”

At the end of the seminar on sex and relationships, we all shuffled out of the venue looking shell-shocked. I knew a couple of my friends had already had sex, and I hated to think what emotions they were trying to process after seeing those ripped-up pieces of paper.

One friend who I knew had been sexually active whispered to me, “What am I going to do now? If I’m damaged, just like that piece of paper, who is ever going to want me?” Tears began trickling out of the corners of her eyes, and she wiped them away, smudging her makeup. “God must be so angry with me …” she added as she walked away in need of some privacy to cry.

Sex had become a regular topic at the Christian events I attended, as soon as my friends and I had hit sixteen. Some of the seminars did better than others at handling this sensitive topic, although even the best ones made it clear sex was only allowed within a heterosexual marriage to another Christian. It was an important evangelical teaching, an unmovable line in the sand. It was the only godly option—everything else was serious sin.

Many times in those talks, I heard St. Paul quoted: “Flee from sexual immorality. All other sins a person commits are outside the body, but whoever sins sexually, sins against their own body” (1 Cor. 6:18, NIV). We were taught that this placed sexual sin above others; it was the most grievous offense against God and against yourself. It frightened our teenage minds, which I think was part of the aim—to scare our hormones into obedience.

At one Christian camp, a visiting American speaker used a different illustration. She held up an apple and, taking a bite out of it, said, “This is an example of what happens when you have sex.” She handed the apple to a person in the front row, instructing, “Take a bite.” The teenager awkwardly chomped into the fruit. “Now hand it to the person next to you,” the leader instructed. Once five people had bitten chunks out of the apple, there was little left but the core. “Hand it back to me,” the leader said, holding out her hand.

“Now,” she said, looking at us, “this is what happens when you give yourself away sexually to multiple people. All you’re left with is this ugly core.” She held what was left of the apple in the air. “Who’s going to want you if you are left like this? What godly man or woman will want to give their life to you then? Stick to God’s way for sex: save it for marriage.”

This area of life was treated with severity in evangelical and Pentecostal churches. I’d heard of several married pastors in the UK who’d lost their job as a result of having an affair. A male youth leader in another city had been fired for sleeping with his girlfriend before they were married. Punishment was seen as helping the sinner get back on track.

Our youth meetings also brought up the topic of masturbation. We were told it was sinful and not something Christians should ever do. Sex and the feelings that went with it were for marriage, not for selfish pleasure. We shouldn’t be “harboring lustful thoughts,” so masturbation had no place in the life of a follower of Jesus. It was a lot to process for all of us, leading to repetitive cycles of guilt, repentance, and more guilt.

American influences were increasingly making their way into British church culture, especially in Pentecostal circles. Speakers and musicians frequently traveled between the two countries, so ideas cross-pollinated. As I attended conferences, listened to tapes, and watched Christian documentaries, I was discovering more of them.

A movement called True Love Waits—also known as the purity movement or abstinence movement—was sweeping the States, and it didn’t take long for it to reach me on British shores. Various authors, speakers, and singers taught an impassioned message insisting not only on no sex before marriage, but also on avoiding any physical affection at all between dating couples.

I watched several documentaries featuring American Christian teens who were choosing not to kiss until their wedding day. “I’m choosing to put Jesus first,” one of them said to the camera in a documentary, “that means choosing the way of the Spirit, not the way of the flesh.” Another said, “Physical intimacy—even a quick kiss—is a slippery slope toward sex, and I’m worried I’ll go too far. Better to avoid anything besides holding hands until marriage. I know it’s what God wants, and I want to please him with my life.”

Spokespeople for the abstinence movement described it as follows: “True Love Waits promotes sexual purity not just in a physical way, but also in a cognitive, spiritual, and behavioral way.” It was all-encompassing; thoughts of sex, sexual feelings, and any physical affection between young people were seen as potentially dangerous. Sexual desire was the enemy, and life was a battlefield where we must wage war against it.

A major book on this theme, I Kissed Dating Goodbye, by Joshua Harris, was published in January 1997, when I was seventeen. His book sold 1.2 million copies worldwide. Harris was a homeschooled, twenty-one-year-old Christian when he wrote it, and he was proud to be a virgin.

The book opens with a story about a young Christian couple, Anna and David, who are soon to be married. One night, Anna has a dream about their wedding day, but gradually it turns into something of a nightmare. In this dream, as she walks down the aisle to David, other girls suddenly start standing up and walking toward him too, taking his hands and standing next to him.

“Who are these girls, David?” Anna asks in the dream, feeling tears welling up.

“They’re girls from my past,” David answers, looking ashamed. “Anna, they don’t mean anything to me now … but I’ve given part of my heart to each of them.” Anna was devastated and David was deeply ashamed as this strange scene unfolded. It left both of them ashamed and uncomfortable, turning a beautiful wedding day into a scene of tears and shame. This was just a dream, but by using it in the opening of the book, Joshua Harris hit home his message about the fallout that not being sexually abstinent could create for any of us. Our own wedding days might turn from a dream to a nightmare.

Reading this was enough to shock any churchgoing teen. It left us anxious and horrified. Harris wasn’t just talking about sex in his analogy; it was about David giving his heart to other girls emotionally too. Emotional closeness was something that should be saved for marriage as well.

Not only were sex and kissing off-limits, according to Harris, but so was dating itself. Dating, he argued, was a selfish approach to relationships. It treated them casually, as something you could start and finish at will. Dating was “a training ground for divorce,” as teens would learn to walk away whenever relationships became difficult.

Harris proposed a different model, known as courtship. This meant spending time with the person you liked only in groups, not one-on-one, and having family members present as much as possible. Also, a guy and girl should only begin courting if they believe it is likely to progress toward a lifelong marriage.

The book contained stories of various young couples who had “strayed” into sex before marriage and (apparently) dealt with debilitating guilt, trauma, and damaged future relationships as a result. It was distressing stuff.

For me, this extreme ideology was strangely appealing; if any Christian teen was keen to distance themselves from the effects of puberty, it was me. Hormones seemed like the ultimate enemy, as they were causing my feelings for girls.

Perhaps, I thought, I can make up for those secret feelings by being a perfect example when it comes to my morals around saving sex for marriage. Someday God will change me, I’ll fall in love with a guy, not a girl, and when I do, we’ll save everything beyond a brief kiss for our wedding night.

The purity movement was encouraging young adults to buy “purity rings” and wear them as a sign of their commitment to stop dating and to save sex for marriage. When I attended a concert that preached this message and sold these rings on a merchandise table, I bought one and put it on.

True Love Waits was igniting a generation of Christian youth, mostly in the US, but also around the world. Other resources followed, to keep us all reading and learning. Josh Harris’s flagship book was still flying off the shelves, and he followed it with sequels, including Not Even a Hint: Guarding Your Heart Against Lust and Boy Meets Girl: Say Hello to Courtship.

Well-known Christian artist Rebecca St. James wrote the foreword to Harris’s first book and, a few years later, released her hit song “Wait for Me,” a prayer for her future husband to remain a virgin until they met and were married, and a promise that she would do the same. The song was nominated for a Dove Award (Christian music’s equivalent of a Grammy) in 2002. Following the song’s success, Rebecca published a book, Wait for Me: Rediscovering the Joy of Purity in Romance, which sold over a hundred thousand copies. The abstinence movement was gathering huge momentum.

Ever a perfectionist and never one to go half measure, I fully embraced the ideas of True Love Waits. Not all of this was entirely bad, but it was certainly extreme, and it damaged my perspectives on sexuality and the body. Seeing my sexuality as the enemy, leading me away from God, provided a religious reason to completely distance myself from my own body.

Slowly, I felt less and less of a connection to my emotions too, and dissociation became my norm. This brought some relief—I now had fewer feelings for girls. But it had far broader consequences; it became harder to feel anything at all. At a high-school parents’ evening, when a teacher praised me in front of my mum and dad for an essay I’d written, I couldn’t even crack a smile. I didn’t feel happiness, or pride, or encouragement. I felt nothing.

“Vicky, you can look pleased if you want,” the teacher remarked jokingly, taken aback by my blank expression. I tried to look happy, but I felt numb and unaffected.

On my sixteenth birthday, when other girls were picking out the shortest dress they could get away with to go on a date with their boyfriend, my parents had asked me, “Vicky, what would you like for your birthday?”

My response? “I’d like two Bibles, please.” I had my eye on two specific versions at our local Christian bookstore in Canterbury. One was a study version—The Spirit-Filled Life Bible—complete with commentary, maps, and translations of Greek and Hebrew words. The second was a contemporary translation—The Message—that put the Bible into everyday language. These were genuinely what I wanted—a way to deepen my faith.

Delighted, I unwrapped and pored over those books, filling them with underlining and notes. I loved God deeply, but faith was starting to get out of balance in my life and becoming a form of escapism. I thought about, read about, and spoke about little else. Prayer and worship provided me with a different reality to live in—a spiritual one. This otherworldly, ethereal realm was easier to focus on than the physical world I was finding so tough to navigate.

Like many evangelical Christians, I got up early each morning and did devotions for an hour, following a daily Bible reading plan. Gradually those morning devotions became more self-critical; I adopted a practice used by John and Charles Wesley, the founders of Methodism, who used to get together for meetings that they called the Holy Club. During those gatherings the Wesleys painstakingly assessed themselves using twenty-two accountability questions that explored how well they’d lived up to God’s standards each day. They listed the good character traits they wanted to see in themselves and examined where they’d failed to live up to them.

Inspired by the Wesleys, in a big blue journal I wrote out accountability questions each night. My perfectionism caught every flaw. I felt I had so much to make up for in life, because I believed I was inherently broken due to my gay feelings.

Alongside all of this, I was getting a steady stream of invitations to play and sing at churches and youth events, and the numbers attending were larger and larger. Other churches had started using my songs in their services too. “Hundreds of young people your age are looking up to you now—make sure you give them a great example to follow,” I was told by well-meaning people. It was exciting to see my music reaching bigger audiences, but responsibility weighed heavy on my shoulders, as did fear and shame.

I wanted to be a Christian musician and a worship leader. I wanted to set a great example and make those around me proud. I wanted to serve God and use the musical gifts he’d entrusted me with. It was terrifying to think of letting everyone down. If my church music career was to grow, I’d need to keep a perfect moral track record. The pressure was on.

On top of this, major change was ahead. High school was nearing its end, and in a year or so I’d be heading to university. Church leaders had warned me that many eighteen-year-olds had gone to university and lost their faith, which alarmed me. I had no idea what sort of ideas or people I would encounter in this future chapter of my life. I’d be away from my family, my church, my youth group; it would be a whole new start—which excited and scared me in equal measure.