По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

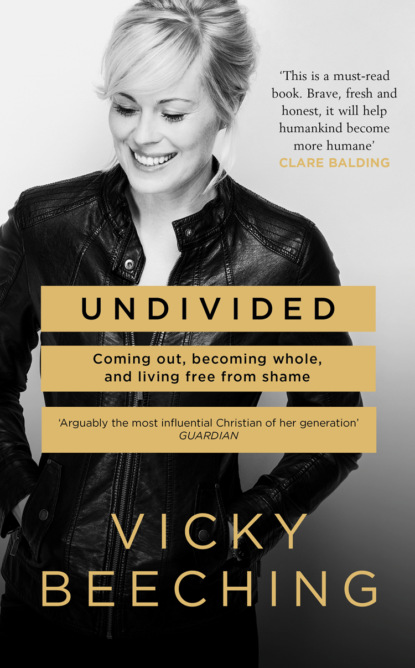

Undivided: Coming Out, Becoming Whole, and Living Free From Shame

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

I was certain I couldn’t hide these thoughts forever. Someone would figure me out, I worried. Acting on any of these attractions wasn’t an option for me—I might have daydreamed about it, but I shut down those thoughts as, to me, they were off-limits and wrong. But I feared my accidental gazes at girls might make people suspicious, and it felt awful.

Honestly, I hoped it was just a phase—I wanted to fit in with my Christian friends and my church; I just wanted to belong. Sneaking away from my parents once at the local library, I found a book about teenage psychology. Flicking to a section on sexual development, I read that lots of young people experienced attraction to people of the same gender for a while and then they grew out of it.

After reading that, my prayers every night—offered with urgency—begged God to help this “phase” come to an end, so that I could stop these sinful thoughts and start living a holy life. The guilt these feelings generated was leaving me feeling paralyzed. I had nowhere to go with them and no one safe to confide in. Would God still love me if I was attracted to girls? I was pretty sure the answer was a resounding no.

Go on, Vicky. It’s just for a weekend,” a school friend said, handing me a paper invitation. “You’ll love it—loads of us are going.”

Despite my increasingly solitary behavior at school, one Christian classmate invited me to a weekend event for church youth. Lately, I’d felt miles away from everyone, behind an invisible wall, trying to navigate the tensions in my life created by this new awareness that I was attracted to girls and not boys. All my friendships had grown distant as I spent my free periods alone in the library writing in my journal or with my Walkman plugged into my ears.

I didn’t feel like being social, but since this would be a conference to develop young adults in their Christian faith, I thought I’d give it a try. It would be held in a beautiful old property in a nearby town and was a Catholic event—something outside my usual Protestant tradition. I was curious and intrigued. “Okay,” I said. “Count me in.”

The weekend arrived, and my initial nerves about being with a roomful of strangers dissipated when someone grabbed a guitar and led worship songs that I was familiar with. I enjoyed the talks, the meals, and, most of all, the singing. But, as always, nagging shame and fear plagued me as I thought about my orientation, knowing that everyone on the weekend would see me in a totally different light if they knew I was gay. Their friendliness would have turned to disapproval and judgment, and I would certainly not have been viewed as an “up-and-coming young faith leader,” as they were describing me there that weekend.

Every time we prayed, and each time we sang a slow song encouraging inner reflection, my mind played the same broken record that beat me up mentally and emotionally for being broken and sinful because of my orientation.

I wondered if maybe, somehow, I could get help that weekend. Perhaps in this more anonymous setting, one of the Catholic leaders could help me? I thought. Whispering a prayer, I asked God for a breakthrough.

On the final afternoon, the event leaders announced that something different would be happening. A priest was visiting for a few hours and would be performing private confessions in a small room down the hall. Any participants wanting to go to confession, to repent of whatever sins they had committed and receive the priest’s absolution (official forgiveness from God), could make their way to that small room and wait their turn.

The Church of England didn’t offer one-on-one confession, neither had my earlier Pentecostal denomination. This was something new to me and I wondered if it might be the key to getting free from my feelings for girls.

Summoning all the courage I had, I made my way down the hallway to the small room and knocked on the dark mahogany door. The sound of that knock seemed to echo for miles, and I blushed, hoping none of my friends knew I was going to see the priest. It could only mean I was struggling with something. And for an “up-and-coming” young Christian leader like me, that was not the impression I wanted to give anyone.

The whole exchange was unfamiliar to me, but the old Catholic priest was friendly and put me at ease. With a smile, he gestured to an empty seat opposite him. After reading some liturgy, the priest wanted to make it more teen-friendly, so he spoke in everyday language: “Are there specific things you’d like to repent of, to say sorry to God for? If there are, just speak them out now, and we’ll give those things to God.”

I listed some minor things—like getting angry, using bad language, and forgetting to do my daily Bible readings. When I left a long pause after this, he sensed that there was something I hadn’t mentioned, the real reason I was there.

“Is there anything else?” he interjected.

I gulped and felt my chest tighten. Desperate for change, for the first time in my life I tried to voice the words: “Um … Yes … I am having feelings for other girls … like gay feelings … and I want to be forgiven for that, and set free from it as I know it’s sinful.”

I hung my head, red-faced, as heavy tears began streaming down my cheeks. It was a shock to hear those words come out of my mouth for the first time.

The priest gave me a kind look and said, “That was very brave. Well, let’s pray, shall we?” Then he read the prayer of absolution, offering my repentance to God and pronouncing his forgiveness over my life. I heard the words, but mostly I was lost in a moment of shock that I’d told someone.

The prayer ended, and he thanked me for dropping in. Surely, I thought, God would see how brave I’d been in speaking out this deeply held secret. Surely, the Catholic priest, with his spiritual authority and the powerful words of the liturgy, would have the ability to change me.

Stepping out of the room, I closed the heavy wooden door behind me. I heard it shut with a loud thud and believed I’d left my sins—my gay feelings, my gay identity—behind that door. Forgiven and set free, I’d stepped out of an old life and into a new one.

But it didn’t take long for me to realize nothing had changed. The feelings remained and with them came the rush of embarrassment and fear. I was crushed—my prayer hadn’t been answered. My moment of courage and honesty with the priest had been for nothing. Perhaps God had forgiven me, according to the priest’s absolution, but he certainly hadn’t set me free.

My head spun with questions, but I had no one to go to with them. That priest had been from another town, and I had no idea how to contact him; to be honest, I was so embarrassed about telling him that I hoped we’d never cross paths again.

I must be so rebellious and sinful, if just hours after the confession I’ve had my old thought patterns return, I thought tearfully. God must be so angry with me. I felt utterly alone and saw no chance of an end to all of my struggles. If even a priest couldn’t break off these chains of sinful feelings, who could? It seemed to me that I must be too broken for even God to fix.

4 (#ulink_5fb40286-cb81-5388-98e1-73c34a3d9ffa)

Transfixed, I stood in the music store, gazing at the most beautiful electric guitar I’d ever seen. It was red and white, modeled after the famous Fender Telecaster—a cheaper version but still stunning to me. The gregarious salesman grabbed a stepladder and got it down, the weight of it surprising me as he handed it over. I plugged it into an amplifier and began to play. My face lit up, and my mother, watching from nearby, could tell I was desperately hoping we might take it home.

We’d only planned to buy a basic, cheap classical guitar that day, something for me to learn on instead of always stealing my mum’s acoustic. But she could tell my heart had attached itself to this red-and-white electric. I agreed that I’d gladly have it as birthday and Christmas gifts all rolled into one. So we left the store with that gorgeous instrument, plus a small practice amp, a tuner pedal, a capo, and all the cables and plectrums I could wish for.

With this new guitar waiting for me each evening when I returned home from high school, I practiced even more than before. Once homework was done, every night I’d close my bedroom door and play, teaching myself from a book and asking Mum for help if I got stuck.

One evening, shut away in my room playing and singing, something unusual happened. Usually I only made up worship songs, taking my lyric ideas directly from parts of the Bible, like the Psalms. But that evening, rather than singing about faith, I found myself writing a love song. And it was about a girl.

After five minutes, I blushed, stopped, and put the guitar away. It felt as though I’d used my musical gift for something wrong and dirty; I’d polluted the beautiful talents God had given me. I put the guitar down, switched off the bedroom light, pulled the curtains open, and stared out at the stars. “Sorry, God,” I whispered. “I won’t do that again. I promise to use my music for one thing only: to glorify you.”

That was the last time I sang about a girl.

Music quickly evolved from a hobby to something more serious. I recorded my first demo during a high-school summer break—a cassette tape with eight of my songs on it. I borrowed the school’s four-track recorder, a now-ancient device that can record four different layers of audio on one cassette. This was long before easily affordable laptops and music software came into being; as I look back, it feels like the technological Dark Ages.

Proficient in several instruments by then, I played guitar, drums, and piano and then layered vocals and harmonies on the four-track tape. Finally, I finished it off with synth pads and some harmonica.

My parents and sister could barely walk around our living room for weeks, as I’d filled it with cables, wires, amplifiers, and instruments. A piece of paper taped to the door, scribbled in my handwriting, read: QUIET PLEASE: RECORDING IN PROGRESS. I’m grateful that my family was infinitely patient and supportive of my musical quest.

Once the finished demo tape was in my hands, I sent it to one of the UK’s biggest Christian record labels. It was a shot in the dark, but worth a go. To my amazement, they chose one of my songs out of thousands of submissions and featured it on a CD. A copy of the album arrived in the mail, and my family and I sat around and listened to it together. My crazy summer of cables, wires, and recording equipment had opened a significant door.

Spurred on by this, I worked on other songs, hopeful that they’d be published and recorded too. The following year, at one of the Christian youth camps I attended, the leader brought me up in front of five thousand attendees and spoke about how impressed he was with my songwriting. After that, other teenagers came up to me all week, saying hello or asking me to sign their copy of the CD. It was heady stuff for someone still in high school, but instead of making me develop an ego, it just fueled my desire to be the best Christian I could be. I didn’t want to let anyone down.

I discovered that plenty of people made a living recording Christian music and touring across the UK, the US, and Canada. Once I knew this, I wondered if it could ever become my full-time career; I certainly hoped it might. It felt like my childhood dream of becoming a missionary, but through music. I want to be a musicianary, I joked to myself. This dream brought up lots of insecurities too—I worried that I wasn’t good enough at singing or songwriting—but most of all it brought up embarrassment about my “secret personal struggles.”

Amid the growing musical opportunities in my teens, my sexuality hadn’t shown any signs of being a phase. My feelings for girls were real as ever. Daily, I played mind games with myself to silence the thoughts. Who you’re attracted to isn’t a big part of life anyway, I told myself. I mean, it’s just one small fraction of what it means to be human. I can shut it out, stay single, and have a perfectly happy and fulfilled future … I was trying to compartmentalize my heart, and silence my emotions, but it was a struggle I couldn’t seem to win.

Because of this, despite the exciting musical doors that were opening, I was feeling less and less enthusiastic about life. As I segmented my identity into good and bad parts, I felt like I was fragmenting. A dark cloud fell from the sky and settled over my mind and heart.

In my anxiety, I created long, detailed prayers that I would recite to myself each time I felt attracted to a girl. It was my own private liturgy—my internal confession booth—in which I told God how sorry I was ten times a day. My mind became a complex place, a far cry from the mind of the simple, happy child I had been before.

Friends in my class noticed a change in my previously carefree personality. I became aloof and felt awkward in my own skin; I slouched my shoulders and didn’t look people in the eye. Mostly I had my Walkman headphones plugged in, shutting out the world, with my midnight-blue denim jacket buttoned all the way up to the top like a suit of armor.

I began throwing my packed lunches away and stopped eating during school hours. I didn’t know how to relate to my body anymore. It seemed to be betraying me with its sinful desires, so I didn’t want to give it food. My flesh and blood were now the enemy; I was fighting a battle against myself.

Do you think there’s any chance he likes me?” one girl asked, looking hopeful, as she ate her sandwich. “I mean, he did sit next to me on the bus the other day—and I could’ve sworn he was looking at my hair and my outfit. I just can’t stop thinking about him.”

I never knew quite how to handle these conversations. I wanted to be part of the crowd, so I listened to my classmates sharing their latest stories. But when someone casually asked me, “So, Vicky, which of the guys do you like? Anyone you’ve got your eye on? Who have you been kissing lately?!” I felt totally stumped. Stumbling over my words, I would say, “Oh, no one really …,” but that recurring answer was only making people ask more frequently, as they were curious.

I’d had my first kiss somewhere around the age of twelve or thirteen. It was with a boy, of course, as girls were, in my mind, forever off-limits. In keeping with my outdoorsy, countryside childhood, it had happened when we were sitting in a field of tall yellow flowers; so tall that they stood far above our heads, swaying in the summer breeze. And the boy I’d sat in tree houses, splashed in rivers, and run through wheat-fields with since we were nine was the one who’d decided to kiss me.

It was a first kiss that almost anyone would treasure, picturesque in location and with someone I cared for. But I felt nothing for him beyond the platonic friendship we’d always shared. My heart was wired differently, so I couldn’t reciprocate his attraction. So my first kiss, despite being a happy memory because of our friendship, was not one I felt a romantic connection to. At the time, I wondered if maybe I would feel something for other guys; perhaps he was more like a brother than a boyfriend to me, I’d thought.

Several other interested boys came and went during my high-school years, mostly just friends I bonded with over guitars. My heart would sink if those guys began looking at me differently, as I knew what was coming. They’d tell me about their feelings, and I’d be forced to choose: try dating them and see if any feelings appeared or admit what I already knew, that I was gay and attraction to boys would never be there.

When one of these male friends tried to kiss me at a bus stop, nothing about it made my heart skip a beat or gave me butterflies—but I did feel all of those things when I looked at the girls I liked. Kissing somebody male felt unnatural and awkward to me, like playing a forced role in the film of my life, an understudy for the person I was trying to become. But it felt important to explore this—I was figuring out who I was, and I was desperate to fit in.

I said yes to dating a few of my male friends, but they were deeply hurt when I broke up with them only weeks into our fledgling relationship. I couldn’t tell them the truth about why I had no attraction to them—so I was left grasping at clichés like “It’s not you; it’s me” or “You’re more like a brother to me.” It was an emotional car crash for both of us every time; we both walked away hurt, and they had a sense of confusion because my reasons for breaking up were never fully convincing.

As my female classmates and I arrived at the legal age of consent to have sex (sixteen years old in the UK), conversations about “fancying boys” became more serious and progressed further. Some of the older girls were claiming to have “gone all the way.” I’m sure much of it was just bravado, but a number of my peers at school were now sexually active. This, in turn, would bring a new degree of heartache for me.

Once, on my way to a science lesson, the blue-eyed girl in my class whom I’d fallen for three years earlier and still couldn’t seem to get over said she wanted to go on a walk with me at break time to tell me something. Getting to spend time with her alone was the Holy Grail for me, and I thought about nothing else all morning.