По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

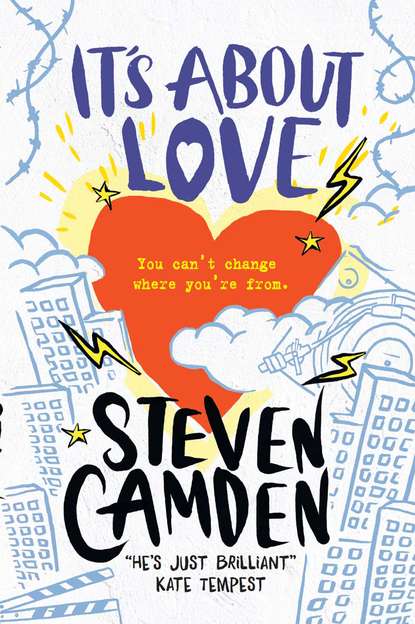

It’s About Love

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

From Mum and Dad’s bedroom window she couldn’t see me.

Every Sunday morning, she’d wheel it out on to the dirty slabs by their back door, flip it over and clean it with a toothbrush.

Her name was Becky.

Something about the way she moved, the care she took, mesmerised me.

I wanted to tell her, let her know I thought she was amazing.

So I wrote her a note, on Dad’s yellow pad, and posted it the day we left to go up and see Uncle Chris in Yorkshire.

The two weeks we were away I thought about her every day. Yorkshire was so boring. Dad and Uncle Chris fixing old bikes. Marc cooking with Mum. There was nothing to do but walk in the wet fields and think about Becky. Her face as she opened the letter. Her writing one back. Me running alongside her as she rode her BMX to the park.

The drive home was all butterflies.

Then we pulled into our road and I saw the SOLD sign straight away. I didn’t even know her house was for sale. Through the front window I could see empty walls and stripped floorboards.

On our door mat, among the post, was a sky-blue envelope with my name on it. I ran upstairs, shut my bedroom door and sat on my bed to read it. All it said was:

I’m on my bed, staring across at my bookcase of DVDs.

My bedside lamp’s pointed up at them like the Twentieth Century Fox spotlight. Mum’s at work at the hospital. It’s just after midnight.

Forget her.

I stare at the DVD spines and picture Leia standing in the underpass, staring confused as I walk away.

Forget her. She’s no different.

But she feels different.

She stared just the same, didn’t she?

My hand comes up to my face. Didn’t she?

My fingertip traces my scar. The curved sickle of torn skin that swoops from above the middle of my left eyebrow, down over my eyelid, across my cheek towards my ear. The glossy smoothness of it. Branding me.

I think about how there’s a version of me, somewhere else, in another universe, without a scar. A sixteen-year-old Luke Henry with a face that isn’t torn, who doesn’t live his life through the stares of strangers. I think about cells. How they die and regenerate and replace themselves and why can’t the cells of a scar be like all the others?

Nan said every scar is the memory of a mistake. A reminder to learn from. I get that. I understand. But do I have to see that memory every day for the rest of my life?

Look at you.

I picture Simeon, head cocked back in laughter, his perfect skin. It’s all so cliché. It can’t be that simple. Surely she can see past it.

What does she see when she looks at me?

Trouble. That’s what she sees. Just like everybody else.

I open my notebook in my lap and stare at the page. Zia’s words from the other day are written at the top: My life is my scrapbook.

My eyes close and my head goes back until it touches the wall behind me.

I use my neck muscles and push back, feeling the pressure in my crown.

“My life is my scrapbook.” Deep breath. “My life is my scrapbook.”

I stare across and read the spines on my top shelf, a jumble-sale mix of films I stole from Dad and Marc and other ones I don’t think either of them have seen; The Conformist, A Room For Romeo Brass, Somebody Up There Likes Me, Buffalo 66.

And then I have an idea.

I’m on my knees pulling out my notebooks. All of them. I spread them out on the floor around me. They’re all A4. Some have scribbled words on the front. Some have doodles and rubbish sketches. One of them has a crude picture of a hand gun in black biro against the brown of its cover. I open it up and flick through, looking for something, then I find it.

We sit opposite each other across the plastic table.

The room has small square windows pushed up near the ceiling and through them it’s afternoon. Spaced out pairs of people all sitting across identical tables from each other. The walls are off-white. A thick-set prison guard stands next to the door. I look across the table at Marc. Nervous. He just stares and says, “You shouldn’t have come.” I want to tell him I wanted to. I had to. He’s my brother. I can help him get through this. But I don’t. I just sit.

Then his skin is changing. Becoming dotted. Grainy. His facial expression doesn’t change, but his skin is becoming sandpaper. Rough and speckled.

“Marc. What’s happening? Marc?”

He doesn’t respond, his skin getting darker and rougher. And then his chin breaks off, the bottom of his jaw crumbling into sand, spilling down his chest. “Marc?” Then his shoulder, like old stone, disintegrates. Then his chest, caving into itself. “Marc!” Then all of him. His neck gives way, then his face, his expression never changing as all of him crumbles away.

I lay the notebook on the floor, open at the page. I can see it. I can see him. And I can use it.

I pick up my new one and I write: Marc

What you doing?

I write Nineteen

What are you doing?

I cross out Nineteen and write Marc. 20 yrs old.

You shouldn’t be writing this.

But I don’t listen. I just carry on.

Marc showers. He dries himself and walks back to his cell. He gets dressed. We can hear shouts and the occasional clank of metal on metal. He folds his towel up and lays it over the back of the chair, watching himself in the small shaving mirror stuck on to the wall above the sink. His dark hair is cut close, light stubble on his top lip and chin, cheeks smooth and fresh. Chiselled.

He stares at his reflection, lowering his chin until it’s almost touching the grey of his sweater, his shoulders rise and fall as he breathes.

Then he speaks. “I’m coming home.”

(#ulink_654a7e98-1e6e-5475-a375-73668bd04c7f)

I’m staring out of the window in comms.