По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

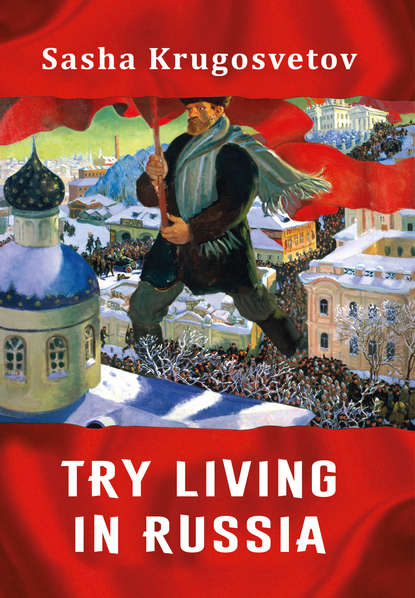

Try living in Russia

Автор

Серия

Год написания книги

2020

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Try living in Russia

Sasha Krugosvetov

London Prize presents

The autobiographical prose of the talented writer who uses the pseudonym Sasha Krugosvetov is aimed at the widest possible audience. The author talks about those events he happened to witness and be part of, as well as about others of which he knows from tales and stories, and about the people whose actions and fates left a trace in the history of the last decades…

Sasha Krugosvetov

Try living in Russia

© Sasha Krugosvetov, 2020

© Josephine von Zitzewitz: the English translation, 2020

© Maxim Sviridenkov: the cover design and the book description on the back cover, 2020; The paintings used in the cover design are Boris Kustodiev's «Bolshevik» (1920) and «Shrovetide» (1916)

© International Union of Writers, 2020

Sasha Krugosvetov

Sasha Krugosvetov is the pen name of Lev Lapkin, a Russian writer and scientist. Born in 1941, he worked in science research and began to write fiction in the early 2010s. For his books, he was awarded several prizes at the Russian-based International Science Fiction and Fantasy Convention, «RosCon» (including 2014 Alisa Award for the best children's fantasy book, 2015 Silver RosCon Award for the best short story book and 2019 Gold RosCon Award for the best novel), the International Adam Mickiewicz Medal (Moscow/Warsaw, 2015) and other prestigious Russian literary awards. His novel, «Dado Island: The Superstitious Democracy» was translated into

Blessed is he who lived

In the world at its fateful hour

He was called by the gods themselves

To join them at the feast.

Fyodor Tyutchev

Orenburg

I've been living in Russia for a hundred years. Since 1913. Although I was born much later.

A hundred years ago my father lived at the edge of Orenburg, a small provincial town in tsarist Russia. Grandfather Mendel, a pious Jewish tailor, had a large family to support. He had five children from his first marriage, three boys and two girls. My father was the middle child, the third. He was right in the middle, with one older and one younger brother and sister each. After the death of my grandmother, whom I never met, my grandfather married a young peasant woman. My parents, uncles and aunts called her Auntie Musya. Auntie Musya bore Mendel a daughter. My father grew up like a selfseeding plant in the steppe. Not very tall, well-built, muscular, opinionated. The winds of the times tried to bend and break him, but he drew himself up and grew strong. Nearby was the Ural River. He would go fishing and swim tirelessly. In the vicinity there were Cossack villages. The boys from these villages would lie in wait for the Jewish kid to teach that infidel a lesson or two about life. He apprehended his offenders one by one and paid them back in kind. The adults were more benevolent. Many had their uniforms made by his father. The family might by yids, but they could be good people nonetheless. Look, they would say, how Yashka vaults his horse. He was able to jump off at a full gallop, touch the earth with his feet and jump back into the saddle with his backside facing forward. And then sit up straight. It's hard for me to imagine what life was like in my grandfather's family. I know that Mendel observed the Jewish feasts strictly. For Easter he would read the Torah, hiding the matzo on the chair under his bottom. The children would try to steal it. That was their custom. If a child managed to steal the matzo, he or she would receive a ransom for it. Grandfather pretended to be angry and did not allow anyone to get close, but somebody would inevitably manage to reach the matzo. Grandfather ostensibly failed to see that person. Did my father spend a lot of time at home? Did he master many of the patriarchal Jewish family customs? I don't know. He mastered neither the Law of Moses, nor the Jewish festivals, nor faith in his Jewish god, nor Yiddish, the second language of Jewish families in tsarist Russia. But for some reason he learned to sew a bit from his father. That I know for sure. There was a period after WWII during which we led a very modest life; I was a schoolboy and my father sewed me several pairs of trousers. His sewing was quite good, and he ironed the trousers exquisitely. And he taught me how to do it myself. I still know how to do it now. He also somehow managed to finish primary school. He finished his school education only after he'd been on civvy street for a bit. And I don't get how he managed to get out of his father's family with cut-glass Russian, no accent at all. And not a single foul word! My father, who lived through three wars… you would hear my uncles and aunts speak the same correct language. They were very simple people, with primary education and then secondary school. That they received a secondary education is entirely to the credit of the Soviet government, which offered opportunities to simple people regardless of their nationality. I never heard anyone in my family use the word «bum» or «piss», not even «take a leak», nothing of that kind, neither words nor jokes nor hints nor indecencies nor euphemisms. My father only ever spoke correct Russian. I can't figure out where he looked for it, how he filtered it out and mastered it in the draughts of the troubled and tragic twentieth century.

The Soviet Regime

My father was fourteen when the Civil War started. He ended up in the Red Army. They made him a mounted orderly. Now it came handy that he knew how to vault. He had a Red Army book that I have kept to this day. He had to fulfil difficult tasks and there were pursuits, too, but the lord spared this nimble, clever lad. Afterwards he worked in a factory. He studied. He took up singing. People kept pushing him, telling him that the opera was beckoning. My father had an amazing bass-baritone voice. «Neither sleep nor rest for the tortured soul. Night brings me no comfort, no forgetting. All that is past I experience again, alone in the silence of the night.» What a mix! Everything was in there – the revolution, the dictatorship of the proletariat, atheism, the accursed bourgeois culture. My father became a Soviet vydvizhenets, a low-ranking worker promoted to a leading role.[1 - A vydvizhenets was a young person with politically correct background and past who was recommended by the communist party for a leadership role in the national economy.] That's understandable and natural. He was of working class origin after all. What is a tailor? Not a peasant, not a landowner, not a general, and not a clerk either. That means he's a worker. My father finished school and found himself in a factory in Petrograd. Then he helped his own ageing father and his siblings to make their way there. How did they live back then? The huge flats that had belonged to members of the bourgeoisie were being cleared of their inhabitants. Rooms that were 30 or 40 square meters in size were partitioned off. Each room was then allocated to a large family. One single flat might consist of ten or even twenty such rooms. To the present day I remember the phantasmagoria of communal flats. I remember my grandfather's flat (or rather, his room in a communal flat) on Borovaya Street. I used to go there after the war, when my grandfather was still alive. What singing career? Forget the opera. The country was seething. There were so many things to do. My father joined the party. Lenin's summons. My father's belief was fierce; everything was now being done for the sake of the working people. As he was hardworking, organised, respectable, a Civil War veteran and a party member, he was quickly promoted to a leadership role. My father wanted to get an education and started a college degree. I'll ran ahead and say that his dream of higher education didn't materialise – there were the communist construction projects, special commissions by the party… «Tell me, Yakov, what is more important to you – college or your party card? You need to go where the party needs you.» The construction of Khibinogorsk. Apatity. Then came the Finnish War. And WWII was drawing near at full speed already. The trumpet kept calling. And then even the trumpet could no longer be heard. In its place came the roar of guns, explosions and friends dying; the everyday military labour that could end only in an early grave or the longawaited victory. But that was later. For now there was the dawn of the young Soviet regime, a happy time for a Jewish lad of modest origins. The fact that a host of atrocities had already been committed by that time, while many poisonous vipers were fighting under the carpet,[2 - Cf. the remark that Russian politics resembles «dogs fighting under a carpet», attributed to Winston Churchill.] that the founders of the «radiant future» were embroiled in a long straggle to get even with each other, that by that moment the dark Eastern genius of the Kremlin had emerged fully-fledged and shown his insidious power… All this was so far away, so entirely incomprehensible to those who were the green shoots of the new Soviet land. The young vydvizhentsy did not reflect on all this; they neither saw nor understood. For them everything was simple. There it was, the bubbling, young ordinary life, so open, so naive, so selfless and honest. Work and turn the fairy tale into a true story. All paths are open to you. You are young and strong. Everything you do will turn out well. A wonderful young country. «We were born…»[3 - The first words of the official hymn of the Soviet Air Force: «We were born to turn the fairy take into a true story, to overcome space and expanse».] What remained behind were years of destitution, humiliation, the Jewish pale. National inequality. Now there was no oppression. No religions. No nations. We are Soviet people. The party leads us, and Stalin is its leader. He is just like us. Simple and easy to understand. But also wise and far-sighted. Do we now have the right to judge those who were young, ardent, genuine, naive and inexperienced then? How many people in the West were taken with the new Russian idea of universal brotherhood! There it was – the city of the sun, about to be built. The Comintern (the Third International). Everybody was waiting for the worldwide proletarian revolution. The communist idea was popular all over the world. Take the French communist and writer Vaillant-Couturier. Or Henri Barbusse, who wrote «Joseph Stalin». «He was a genuine leader, a man whom the workers discussed, smiling with joy at the fact that he was both their comrade and their teacher; he was the father and older brother, really watching over all of us. You didn't know him but he knew you; he was thinking about you. No matter who you were, you were in need of precisely such a friend. And no matter who you are, the best elements of your fate were in the hands of this other person, who was also keeping watch on behalf of everybody, working; this man with the head of a scholar, the face of a worker and the clothes of a simple soldier.» When Henri Barbusse, the French writer, journalist and public figure, the laureate of the prestigious French Prix Goncourt, sang the praises of the Great Stalin, he wrote from the heart, wrote what he was thinking. So what do we expect of our inexperienced, simple-minded fathers?

The New Economic Policy and Khibinogorsk

My mother is from Odessa. My maternal grandfather was a huge, pure-bred, handsome blond man. His surname was Koch, let's face it, not a popular name during the war. Running ahead, I'll tell you that my mother didn't change her surname when she got married and that, as it turned out, hadn't been the best of decisions. There were three daughters and one son in the family. The children were well dressed, the girls all in ruches. My grandmother was a real character, the pillar of the household. There was nothing Jewish about that family apart from its origin. Neither language nor religion. I don't know why. Everybody spoke wonderful Russian, not even a Ukrainian accent. I can't tell you the reason for that either. My mother, Lyuba, was the middle daughter. The most accomplished one. The one everybody loved best was Galya, the youngest, who was considered the most beautiful. When I began to understand certain things, this didn't seem obvious to me at all – my mother is significantly more interesting than Galya, perhaps because her entire character was more animated. The oldest daughter, Dora, who was also the oldest child, was, naturally, the first one, and was loved out of habit and inertia. Dora was unlucky; she was pitied, watched over and protected. Semyon, the son, my uncle, was tall as his father, clumsy, bashful, with no real predisposition for any one thing, although he was a good student and the only one in our family to gain a degree in engineering. Nobody paid attention to my mother in her father's house – she was clever, joyful, resilient, independent, lively, sociable, balanced, pretty, she would make her way regardless. During the evacuation in the war, when my grandfather was gone already… The husbands of her daughters were at the front. My grandmother remained behind with three daughters and three grandchildren… Everything fell onto her shoulders, which were no longer young. Grandmother suffered from high blood pressure; the high mountains of the Urals were not for her. Poor grandmother. In the evening the whole family was sitting at the table, she was laughing, joking… and suddenly it all came to an end in front of her daughters. Life was cut short in flight. Her speech faltered, she only managed to say one thing: «Lyuba, look after Dora and Galya.» And then she was gone. She had managed to say the most important thing. She knew that she could count on Lyuba for anything. But that will come later. For the time being all was well in the family of my grandparents. The children were going to school. The country was ruled by the New Economic Policy – NEP Grandfather had his own «business». A tragic story that is comic at the same time. Grandfather's business partner was a sprightly young lad. He used to come to the house frequently, spending time in the company of the three marriageable young ladies. Perhaps they weren't the most beautiful, but they were pure, neat and intelligent. A real pleasure. He managed to turn the oldest girl's head, promising to marry her and seducing her on the sly. Then he took the cash register and that was the last we saw of him. Gone. The oldest daughter in tears and with a broken heart. The business bust. The disgrace to be seen by the whole of Odessa. Perhaps for this reason, perhaps for another, the family scraped together the last of their money and left for Petrograd. That was the script of providence. At first they lived in a communal flat on Mokhovaya Street, then on the Old Nevsky Prospekt. How they made ends meet is hard to say. The children were grown, the daughters were going to school, the son was working already. The inconsolable girl who'd been «jilted and abandoned» was married off upon arrival. The parents found an unprepossessing Jew, kindhearted, plump and no longer young. He had an amazing instinct for business, a characteristic that is common among the people of the Book. He was the commercial director of a furniture factory and rather well-off for by the standards of those dark times. He was glad to be married. How they made Dora agree I don't know. Perhaps she understood that such a marriage was necessary in order to solve the family's financial problems. She never looked happy. I never saw her smile. But she was a good wife. She was faithful and maintained her family as best she could. The daughter she had was the first granddaughter in a large family and everyone's darling. But with her husband she was strict. This tradition to keep one's husband under the thumb was subsequently passed down to every single woman in Auntie Dora's lineage.

My grandfather was soon arrested by the secret police. They were arresting all the NEP-men and confiscating their gold. And he, the unsuccessful NEP-man, was arrested, too. He, the NEP-man who had had his «business» stolen, together with his money and the honour of his elder daughter. What did that matter to those guys? Give it to us here and now! Not long ago I visited the Solovetsky Islands. I walked around and thought about where my grandfather might have been. Where was he locked up, in which building? My mother abandoned her studies. She made the rounds of the official channels, travelling to Odessa and, for some reason, to Rostov-on-the-Don. She collected many certificates, went to different offices, trying to prove that they had ceased being bourgeois NEP-men long ago and were now honest members of the working class. I don't know whether it was her efforts that did it or whether the screws at that point still hadn't totally lost their mind from the smell of blood. Anyway, my grandfather returned home. Why did they forgive him, why did they leave him alive? Perhaps the screws had made a mistake. I know that many screws of the first wave were shot on the Solovetsky Islands. Perhaps because they sometimes released somebody's grandmothers and – fathers. Without conforming to the important principles of supreme proletarian justice.

However, the good times didn't last long in the old communal flat on Nevsky Prospekt. The problem was that my grandfather had been repeatedly put through the «steam room» when he was on the Solovetsky Islands. Narrow benches were placed into a small room and the prisoners were made to sit astride these benches, very close together, belly to back. Then they'd fill the room with steam. To make the prisoners suffer. To make them realise that they had to surrender what they had unrighteously amassed to the country of the working people. My grandfather returned from the Solovetsky Islands suffering from severe asthma. He died shortly afterwards.

My mother was the next candidate for marriage. We've kept a portrait of hers, drawn in red sangina pencil by an unnamed suitor who had made, as they say, a spectacular career. In the family album there is the portrait of an elegant man with a violin, who apparently had also shown interest in my dear mother before she got married. But for some reason she married my father. He was of very modest means, not very educated, not at all handsome and eight years her senior. Perhaps my mother, wise even in her youth and frightened by the unpredictable turns and harsh reality of the dictatorship of the proletariat, consciously chose a successful and, in those years, fairly influential Soviet riser-through-the-ranks. Or perhaps she had discerned his generous nature, the strength and courage of his character, and his particular masculine type. It's hard for me to tell. The photographs from this time, taken when I wasn't yet born, during my parents' holidays in the Crimea, in the Caucasus, among the snowdrifts of Khibinogorsk where my father was sent on party orders, show an absolutely happy couple. Against the backdrop of glittering snow my father, torso naked, pushes his treasure in a huge wheelbarrow – my mother, clad in a thin crepe-de-chine dress. Life was smiling at them. This was a couple, a family, a union of two complex individuals who faced a very difficult fate. Their relationship, open, kind, selfless and devoted during happy moments as well as life's harsh trials, has been and will remain to me the exemplary, ideal relationship between a man and a woman.

The Northern Caucasus

The Soviet regime provided many people with the opportunity to receive a previously inaccessible higher education. Samuil graduated from medical school in the 1920s and left his native Rostov-on-the-Don on an assignment to the Northern Caucasus. He worked in hospitals and sanatoriums in Sernovodsk, Zheleznovodsk, and Piatigorsk. The clan from Rostov dreamt that the boy might finally settle down and marry a nice Jewish girl. Samuil had his own ideas regarding life. Medicine came first. Medicine was his calling. Behind the plain exterior there was a strong, resolute character. He was a good doctor, organised, knowledgeable and capable of holding his own when it came to treating a patient. He had instinct and intuition. And, most importantly, he loved his patients. That's why he could intuit what they felt. That's why he became a good doctor. And an excellent administrator. He was head of several sanatoriums, one after the other. With regard to having a Jewish wife – no, please don't start. I know what these wives are like. They sleep until midday, and around 2pm they utter the first words: «Syoma, everything hurts!» Samuil loved Tonya Fedotova, who came from an educated, well-to-do intelligentsia family. Every conceivable ethnicity was mixed into this family: there were Russian roots, Terek Cossack influence, Georgian blood and possibly a drop of Turkish blood, too. Tonya was the younger of two sisters. She was not as beautiful as the elder sister, Tanya. But my god, what a woman she was. Delicate and feminine. Slim, well-proportioned, with the Madonna's sad face. Just like Vera Kholodnaya. She played the piano and sang in a quiet voice, kept a diary and wrote poetry. Syoma knew exactly what he needed from life. How could he not have fallen in love with Antonina? If there is a young man among the readers of this sketch, listen to your older comrade. If you happen to meet a woman with a quiet voice who is not talkative and modestly averts her pensive eyes, concealed behind long lashes, don't dismiss her, don't walk past this rare stroke of luck. The strongest, most faithful, selfless and fervent female natures are hiding behind such lowly beauty, such quiet charm. It is them who bestow upon their chosen one the most passionate embraces and become his faithful support for life.

Samuil and Tonya got married. Tonya bore two sons, Vova and Misha, two years apart in age. The chief doctor was a well-respected man. His family received a flat with three rooms. Samuil gave one room to a woman without a family, a fellow doctor at his sanatorium. He had decided that two rooms were enough for his family. Antonina was very hospitable. The doors were always half open. The house was furnished with ascetic simplicity: hospital bunks, a wardrobe, table and chairs. No other furniture whatsoever. In their place a piano, a splendid library and many guests. Antonina, slow by nature, would get up at six in the morning, run to the market, then cook. She managed to feed everybody. Anyone could turn to her family and ask for help. Some insolent women came regularly, asking for money. And Antonina would slip them something. When she had no money, she would give them food, milk, eggs, everything she had. She was incapable of turning anybody away. Acquaintances and others who had come to the resort but didn't know her well would stay at the house. Everybody, apart from Samuil's relations. They couldn't forgive his choice of a wife. They still refused to recognise Antonina and her children. The children hardly knew their father's relatives. However, all their life the children entertained a very close relationship with the beautiful Tanya, Auntie Tanya. I'll charge ahead and tell you that Misha told Tanya things he wouldn't have told his own mother.

The boys were taught music and drawing. They were very capable children. Their school grades were excellent, and both had a gift for the exact sciences. The elder, Volodya, played the violin. He was a fine draftsman, able to create with a single stroke, a single line, the image of a person or outline a landscape. The younger brother, Mishka, played the piano. However, the boys weren't mollycoddled or kept indoors. Let's remember the atmosphere of a warm, southern resort town – the atmosphere of perennial feast. A host of holidaymakers, visitors from the large cities. An abundance of fruit. And an abundance of temptations. Just as all other local children, the boys ran wild in the street, made friends with the people from Caucasus, went to the mountains, climbed trees and collected mulberries. They grew up real tomboys. Once they were chasing each other and Vova slammed the door in Misha's face, bam! Now his brother had a huge conk where his nose was meant to be. And so Misha went through life with a broken, squashed nose. Another time Misha was running after Vova, threatening him with a hot iron, and when he caught up with him he pressed the iron against his bottom, and so Vova was left with the imprint of the iron for life. Antonina decided to get an education and enrolled at the Medical Institute. On the very first day of her course her neighbours told her in the evening that they had seen her dear boys walk along the cornice of the fifth floor. There could be no talk of lectures or study. Oh, it seems that Tonya's dreams of a degree, her dreams to raise her boys to become musicians, writers, artists or doctors, were all in vain. These dreams weren't meant to come true. The younger, Misha, turned out particularly sprightly. He was lively, always laughing and very kind, and as a result everybody loved him, his peers as well as the adults. And whether through constant exposure to the sun or by nature, he was not just sun-bronzed, but downright black. Black like some Indians. Mishka-the-Black, his friends would call him. And that nickname stayed with him to the end of his life. Misha loved to play billiard. He reckoned that he had to know how to do all things better than the others. Sometimes, professional billiard players would come to the sanatorium. One of them became the boy's patron and trained him rather well. Before the outbreak of the war the short ten-year old boy was a very decent player already. Whenever someone came who wanted to play for money, some new artist on tour, Misha's billiard mentor would deploy his favourite trick. Not so quick, he would say. Why don't you first play the lad over there. People would quickly gather for their favourite spectacle. The «lad» would clamber onto a chair, as he couldn't reach the balls standing on the floor. And then he would tear the guest artist to shreds, to everyone's amusement. Yes, it didn't look as if Misha would become a pianist or writer. The country was troubled. Sometimes there was trouble in this god-protected house, too. The terrible year 1937 began to ramble and roar and then exploded in claps of thunder. «Oh how I want to fly away, unseen by anyone, fly off after a ray of light and not exist at all», wrote Mandel'shtam. We won't manage to fly away, Osip Emil'evich, we won't manage to hide or turn into an invisible ray. The local NKVD was given an order; they had to uncover and arrest several thousand hidden enemies of the people. A number of them were to be executed, the other part to be sent to the GULAG. Committees of three NKVD-members were formed, arrests prepared. Lists were compiled of Trotskyites, anti-party groups, kulaks, accomplices of the White Army, spies, war specialists involved in subversive acts, saboteurs, other alien elements. Let's have a heart-to-heart with them, they will confirm everything. Sernovodsk is a small town, everybody knew at whose house the black police car would call next during the night. In the chief doctor's house they were expecting visitors, too. The family was saved by the Chechens. They loved Samuil and decided to help. Old men in burkas came and sat down in the sanatorium's courtyard. «Samuil, don't go home. Stay here for a bit. We've told your family. They won't worry. We'll see what happens.» Every child in town knew about the Chechens in the sanatorium. For the NKVD this was an unexpected turn. There could be unforeseen disturbances. They'd get a rap on the knuckles in Moscow for this. To hell with that Samuil. May he live and work for the good of the proletarian state. He's a good doctor, isn't her? Well, let him work then. We'll manage without including him in our report. Perhaps it really happened like that. Perhaps the Chechens simply hid the chief doctor, his wife and children for a while. Whatever happened, the storm passed by Samuil and his family. But for how long? Hard to predict how the events would have unfolded further. A huge, cruel, merciless war appeared at the threshold, a war that jumbled everyone and everything and destroyed all plans to build a «peaceful» life in the land of the Soviets. During the war, a torrent of casualties flooded from the frontline into the North Caucasus. The sanatorium was transformed into a war hospital. Samuil, the sanatorium's chief doctor, became head of the hospital. His non-proletarian origin didn't stand in the way of his appointment.

The Great Fatherland War

I know little about my father's involvement in the Finnish war. Perhaps he fought only for a short time or not at the main stretch of the front. My father didn't talk about it much. He told something about Finnish snipers at the top of the fir trees and about how dexterous the Fins were at throwing knives. All the rest is muddled. By contrast, WWII, the Great Fatherland War, affected us to the full extent. Just before the war my parents received their own living space. As a fairly highly positioned leader, my father was assigned a flat with two rooms on Liteiny Prospekt. My mother was already pregnant with me. My father decided that a certain colleague of his, who already had a child, needed a separate flat more urgently and ceded the flat. For his own family he took a room in a communal flat, also on Liteiny Prospekt. True, there weren't many other people in that communal flat, which also consisted of two rooms. Our room was large, more than thirty square meters. On the third floor, without a lift. With a stove for heating. My parents only spent a very short time there at first. The war had broken out. My father was preparing his factory's evacuation to the Urals. He sent my grandmother's entire extended family (my aunts, their husbands and children, my uncle) to Sverdlovsk – that was the name of Ekaterinburg in Soviet Russia – and then he sent my mother with her baby bump there, too. She delivered me en route. Well, not on the train, naturally. When she went into labour she was swiftly made to disembark in the town of Galich, Kostroma region, where I came into this world in August 1941. Thus I saw the ancient town of Galich only once. In the following my mother made her own way to Sverdlovsk, with a nursing infant. The food was terrible. She would travel in a heated goods carriage. There was no opportunity to wash. The baby – that is, me – was covered in scabs. Instead of a crib I slept in a wooden trough. She was surrounded by men, soldiers, who had been sent down from the front for various reasons. The soldiers, who were occupying the upper levels of the bunks, picked out lice from under their armpits and dropped them. My mother cried. A wounded officer with heart disease, on his way to a home visit, lowered his head from the second bunk and said, «Don't cry, dear mother, when you son grows up he'll be a Hercules.» As if he'd looked into the future. He was almost right – I grew up to become a big, strong man. With time. Back then what was there was there.

When my mother rejoined my grandmother everyday life became easier, it seems. Although the issue of food remained, of course. It was the same for everyone at that time. Soon afterwards my father moved to the Urals with his family. My mother proudly presented him her cachetic, malnourished baby boy, evidently. Women always show their newborn babies to their beloved husbands in this way. And of course my parents' family joy was once again short-lived. My father, who would always give in to my mother in all matters and consider her opinion in literally all matters, became a very decisive man in those critical moments in life. He was vice director of a huge factory of defensive significance, exempt from military service due to his obligations at the factory and, at 38, was entering middle age. And he enlisted as a volunteer. As a rank-and-file soldier. He told my mother only when he was about to leave.

What do I remember from that time? Almost nothing. A dark stairwell. Some logs that had been stacked on the landing for some reason. A white cat playing among them. Looking at me. My future life, the bright bits and the troubled ones all together, were looking at me through that cat's child-like feral eyes. I remember stories. How my mother took up smoking. Makhorka, rough-cut tobacco. There was nothing else. How my grandmother died. How we waited for the rare letters from the front. How we listened to the song «Wait for Me and I Will Return», how we hoped and cried in silence. How the children greedily snapped up food when there was any in the house. How they swallowed quickly and growled, unable to wait for the next spoonful of porridge. The entire country lived like that. Some faded photographs from that time have survived. My mother, haggard and almost unrecognisable. Huge eyes, a prematurely aged face with a tortured expression. And a terrible puny creature, all skin and bones. That is me. In my eyes, the same suffering as in my mother's.

In 1944 we returned to our flat on Liteiny Prospekt. All our things and furniture had been taken away. By our neighbours from upstairs. My mother didn't argue with anyone. She started again, from scratch. Her sisters and brother came to her aid. Then the war was over. The men returned from the front. In the streets there were flowers, songs, accordion tunes. No news of my father. One joyful soldier in a shirt turned to me in the street, smiled at me and waved. I ran towards him, screaming 'Uncle Daddy!' I didn't know my own father after all. Then the news came that the units of the Second Ukrainian Regiment were still in Prague. That's where my father was. There, the war was still going on; people were dying. While here, peaceful life was beginning. Shops opened. One event that has stayed with me is the opening of a bakery on Liteiny Prospekt. I can still remember it. For some reason my strongest childhood impression was a loaf of white bread on the table. Bulka, as they call white bread in Leningrad.

My father's commander was travelling through Leningrad. «Wait for your husband, Lyubochka, he'll come soon. Your Yasha will return as a Hero of the Soviet Union. All documents are prepared already.» If only it had happened that way. Perhaps many of the subsequent problems in my family would never have arisen. But it turned out differently. Somewhere in the headquarters they had changed the nomination for the Gold Star of the Hero and my father was awarded the Order of the Red Banner instead. My father never pleaded on his own behalf and did not appeal to his front commander.

Who thought of those things back then? The war was over. My father was safe and sound. Almost everyone was safe. The only person in my father's huge family who had died was his older brother. His beloved younger brother Borya returned from captivity. He had pretended to be Tartar and thus saved his own life. What joy that was! My grandmother's entire family, all together. The only one missing was my grandmother herself. My father was jolly and strong. He would sing arias, everybody would start dancing. He would hug my mother and her two sisters to himself, lift them up and waltz around with them. Everybody idolised my father. He was a real hero, his chest covered in orders. Twelve military honours. He would drink a whole bottle of vodka in one go, to the Victory.

So many things remained in the past. He had suffered concussion when a mine exploded next to him. The left side of his body was left paralysed. He'd only just recovered a bit in hospital when he left in a hurry to catch up with his unit. The left side of his face remained immobile for a long time. On one of the photographs from the front his face looks contorted. My father was older than the other front soldiers; they used to call him 'batya', father. Fate saved him from the bullets. But his life could have come to an end for a different reason. My father was a signalman. Once, near Kursk, he and a group of fighters were given the task to set up communication links between our sub-units. With spools of wire on their backs and submachine-guns they had to fight their way through this layer cake of Russian and German positions and return to the position of their unit. Several groups had already been sent on this mission; all had perished. The fighting lasted several days. They completed the task. My father returned and went to the staff quarters to report. An officer he didn't know held forth: «We are risking our lives here while the yids are taking cover behind the front line.» My father threw himself at the officer and hit him in the odious face with a brick. So he came to face trial. According to martial law he should have been shot. What his commander did in order to save him I don't know. They hushed up the story somehow. How they managed to get past the «smershevtsy» – Soviet counterintelligence – I don't know either. God averted them. And the commander. A courageous, noble man. Moreover, he took the risk upon himself. My father received the next award. And in winter 1945 he was nominated for the Star of the Hero for the forced crossing of the river Oder. The Red Army had captured a bridgehead on the other bank. My father's men had to establish a signal connection. They were crawling across the ice with their spools. A mine exploded next to my father, the ice broke, and the massively heavy spool dragged him down, underwater. A very young boy, a signalman from his section, held a pole into the water, which my father managed to grab. Lucky him. He clambered out of the icy water. The section moved on. They established the connection. That's what my father told me. For this action he was nominated for the Hero.

Recently my son found a copy of the original documents nominating my father for his awards on the website «Openaccess database of documents 'The People's Victory in the Great Fatherland War 1941-45'». Look, he said, grandfather was a «terminator». This is what's written, in black and white, in careful handwriting, in the official document on the grounds of which my father received the Order of the Red Banner:

«Sergeant major – surname, name, patronymic – displayed extraordinary courage, self-control, bravery and heroism during the forced crossing of the river Oder and the storming of a heavily fortified defence position on German territory.

In command of a telegraph unit, he inspired his subordinates to military feats by personal example.

Several times he personally removed interruptions to the signal line.

On 26 January 1945 he shot five Nazis at point blank while on his military mission and the signal connection was established in time.

For the forced crossing of the river Oder and the storming of a heavily fortified enemy defence position sergeant major – surname, name, patronymic – is deserving of the Highest Government Award, i. e. the title of Hero of the Soviet Union, the Order of Lenin and the token of particular excellence, the Gold Star Medal».

Let us return to those post-war years. It's all in the past now. The only thing that matters now is to live. Perhaps these were our family's best years. But they were also very difficult years.

The Blockade

No questions here and no decisions

But abundance and a steely order:

Whether you chose the thick of things or lived on the side

Lie down now, someone will stand beside.

E. Kliachkin

Dusya, sturdy, strong, full of vitality, with small eyes and clear traces of the Tartar-Mongol invasion in her face, was left to her own devices during the Blockade, with two girls of ten and twelve to look after. At first the girls had been in the evacuation. Then rumours appeared that the trains full of children were being bombed. Dusya threw herself at the feet of her boss, imploring «I won't ran away, let me go and get my kids!» She managed to get permission for a trip, located her daughters in Valdai and took them back to Leningrad. There they lived through the entire blockade together with their mother.

Dusya came from the town of Torzhok, from a prosperous peasant family. In the past they had been «middle peasants», not rich, but well-to-do. Dusya was sullen and silent. Muscular and strong. With large, unfeminine hands and feet. Her education consisted of four years of parish school. Her husband, Nikolai, was tall and very handsome. With large brown eyes. They had been introduced by Nikolai's mother, a smart peasant women with business sense, a former innkeeper who sometimes travelled from Petersburg to Torzhok. Dusya was 22, by the standards of the time an old maid already. She had had a groom once. A good-for-nothing, when he was drank he would ran through the streets with a rifle and fire at random. They had to get rid of such a groom. On top of that Dusya didn't love him. It would be good to marry her off to a man from the city. Their parents matched Nikolai and Dusya up and married them. They spent a lot of time apart. Nikolai in Petersburg and Dusya in Torzhok. They lived without love. But they managed to have two daughters who, naturally, lived with their mother. Only right before the war did the family manage to find housing in a suburb of Leningrad and started living together. At that time Nikolai had just finished technical college. He became a production engineer. They were very different, Nikolai and Dusya. Nikolai used to read books and wear eyeglasses. Even with his glasses his eyesight was zero. Dusya thought little of her husband. A man who was good for nothing. Incapable of lifting stuff. Of getting things done. Of taking a decision, hammering a nail into the wall. He kept forgetting everything. A bungler. Constantly thinking about something. Lazy and useless. He brought his food ration home, at least something. Well no, Nikolai wasn't quite as useless and clumsy. Before he graduated from technical college he had been a worker at the Putilov Factory, and he'd coped well with the workload. He hadn't been sent to the front because of his eyesight. Certificate of exemption from military service. And suddenly… In the changing room someone took his documents from his clothes. Stole them. Perhaps it didn't happen in the changing room; perhaps someone picked them from his back pocket in the street. Somebody was very keen to help himself to a passport with an exemption certificate inside in these war times. Just at that moment recruitment was underway for the emergency volunteer corps. For some reason recruitment was always underway for the volunteer corps. Come on, Nikolai. We must defend the city against the enemy. We need to get a company together. That's an order. What exemption certificate? Where is it, your exemption certificate? Oh, you don't have it? Where nothing is, nothing can be had. What do you mean, you don't see a thing? Can you see five meters ahead? Do you see the rifle in the corner over there? Take it, and into service with you. There. We'll put a tick there. Nikolai Oref'ev the fighter. What kind of a fighter was he when he couldn't see further than his own hand even when wearing his eyeglasses? So he left with the emergency volunteer corps, to fight in the Siniavinsk swamps. And he didn't send a single message to either Dusya-Evdokia or his girls. Not a single triangular envelope. Not a single message. And no «killed in action» notice either. He vanished just as he had left. What kind of a fighter was he? His eyesight was zero point zero. He disappeared without a trace. He vanished to rot in the icy cold slush of the swamp. And left Dusya to fight for herself with the two girls. No, there is no monument to the fighter Nikolai Sergeevich Oref'ev anywhere in the world. To him who was fashioned from different stuff. For a life in a different space and a different time. Who ended up in this incomprehensible, terrible world and lived here as best he could, preserving his immortal soul as best he could. He chose a woman, not the most beautiful woman, but one who was strong and stubborn and capable of saving and protecting two thoughtless, long-legged girls. What could he have done? He joined the emergency voluntary corps to shield the city against the enemy with his own body. In order to… «lie down in peace when the time comes». «The green leaf from the dead head will cover them all – the gentle and the violent alike.» He left two girls behind. He left fragments of his genes to his offspring. The pensive penchant for quiet reflection. Great sensitivity. And unusually beautiful, eastern, slightly slanted eyes. Those were passed right down to my youngest along the generations.

Sasha Krugosvetov

London Prize presents

The autobiographical prose of the talented writer who uses the pseudonym Sasha Krugosvetov is aimed at the widest possible audience. The author talks about those events he happened to witness and be part of, as well as about others of which he knows from tales and stories, and about the people whose actions and fates left a trace in the history of the last decades…

Sasha Krugosvetov

Try living in Russia

© Sasha Krugosvetov, 2020

© Josephine von Zitzewitz: the English translation, 2020

© Maxim Sviridenkov: the cover design and the book description on the back cover, 2020; The paintings used in the cover design are Boris Kustodiev's «Bolshevik» (1920) and «Shrovetide» (1916)

© International Union of Writers, 2020

Sasha Krugosvetov

Sasha Krugosvetov is the pen name of Lev Lapkin, a Russian writer and scientist. Born in 1941, he worked in science research and began to write fiction in the early 2010s. For his books, he was awarded several prizes at the Russian-based International Science Fiction and Fantasy Convention, «RosCon» (including 2014 Alisa Award for the best children's fantasy book, 2015 Silver RosCon Award for the best short story book and 2019 Gold RosCon Award for the best novel), the International Adam Mickiewicz Medal (Moscow/Warsaw, 2015) and other prestigious Russian literary awards. His novel, «Dado Island: The Superstitious Democracy» was translated into

Blessed is he who lived

In the world at its fateful hour

He was called by the gods themselves

To join them at the feast.

Fyodor Tyutchev

Orenburg

I've been living in Russia for a hundred years. Since 1913. Although I was born much later.

A hundred years ago my father lived at the edge of Orenburg, a small provincial town in tsarist Russia. Grandfather Mendel, a pious Jewish tailor, had a large family to support. He had five children from his first marriage, three boys and two girls. My father was the middle child, the third. He was right in the middle, with one older and one younger brother and sister each. After the death of my grandmother, whom I never met, my grandfather married a young peasant woman. My parents, uncles and aunts called her Auntie Musya. Auntie Musya bore Mendel a daughter. My father grew up like a selfseeding plant in the steppe. Not very tall, well-built, muscular, opinionated. The winds of the times tried to bend and break him, but he drew himself up and grew strong. Nearby was the Ural River. He would go fishing and swim tirelessly. In the vicinity there were Cossack villages. The boys from these villages would lie in wait for the Jewish kid to teach that infidel a lesson or two about life. He apprehended his offenders one by one and paid them back in kind. The adults were more benevolent. Many had their uniforms made by his father. The family might by yids, but they could be good people nonetheless. Look, they would say, how Yashka vaults his horse. He was able to jump off at a full gallop, touch the earth with his feet and jump back into the saddle with his backside facing forward. And then sit up straight. It's hard for me to imagine what life was like in my grandfather's family. I know that Mendel observed the Jewish feasts strictly. For Easter he would read the Torah, hiding the matzo on the chair under his bottom. The children would try to steal it. That was their custom. If a child managed to steal the matzo, he or she would receive a ransom for it. Grandfather pretended to be angry and did not allow anyone to get close, but somebody would inevitably manage to reach the matzo. Grandfather ostensibly failed to see that person. Did my father spend a lot of time at home? Did he master many of the patriarchal Jewish family customs? I don't know. He mastered neither the Law of Moses, nor the Jewish festivals, nor faith in his Jewish god, nor Yiddish, the second language of Jewish families in tsarist Russia. But for some reason he learned to sew a bit from his father. That I know for sure. There was a period after WWII during which we led a very modest life; I was a schoolboy and my father sewed me several pairs of trousers. His sewing was quite good, and he ironed the trousers exquisitely. And he taught me how to do it myself. I still know how to do it now. He also somehow managed to finish primary school. He finished his school education only after he'd been on civvy street for a bit. And I don't get how he managed to get out of his father's family with cut-glass Russian, no accent at all. And not a single foul word! My father, who lived through three wars… you would hear my uncles and aunts speak the same correct language. They were very simple people, with primary education and then secondary school. That they received a secondary education is entirely to the credit of the Soviet government, which offered opportunities to simple people regardless of their nationality. I never heard anyone in my family use the word «bum» or «piss», not even «take a leak», nothing of that kind, neither words nor jokes nor hints nor indecencies nor euphemisms. My father only ever spoke correct Russian. I can't figure out where he looked for it, how he filtered it out and mastered it in the draughts of the troubled and tragic twentieth century.

The Soviet Regime

My father was fourteen when the Civil War started. He ended up in the Red Army. They made him a mounted orderly. Now it came handy that he knew how to vault. He had a Red Army book that I have kept to this day. He had to fulfil difficult tasks and there were pursuits, too, but the lord spared this nimble, clever lad. Afterwards he worked in a factory. He studied. He took up singing. People kept pushing him, telling him that the opera was beckoning. My father had an amazing bass-baritone voice. «Neither sleep nor rest for the tortured soul. Night brings me no comfort, no forgetting. All that is past I experience again, alone in the silence of the night.» What a mix! Everything was in there – the revolution, the dictatorship of the proletariat, atheism, the accursed bourgeois culture. My father became a Soviet vydvizhenets, a low-ranking worker promoted to a leading role.[1 - A vydvizhenets was a young person with politically correct background and past who was recommended by the communist party for a leadership role in the national economy.] That's understandable and natural. He was of working class origin after all. What is a tailor? Not a peasant, not a landowner, not a general, and not a clerk either. That means he's a worker. My father finished school and found himself in a factory in Petrograd. Then he helped his own ageing father and his siblings to make their way there. How did they live back then? The huge flats that had belonged to members of the bourgeoisie were being cleared of their inhabitants. Rooms that were 30 or 40 square meters in size were partitioned off. Each room was then allocated to a large family. One single flat might consist of ten or even twenty such rooms. To the present day I remember the phantasmagoria of communal flats. I remember my grandfather's flat (or rather, his room in a communal flat) on Borovaya Street. I used to go there after the war, when my grandfather was still alive. What singing career? Forget the opera. The country was seething. There were so many things to do. My father joined the party. Lenin's summons. My father's belief was fierce; everything was now being done for the sake of the working people. As he was hardworking, organised, respectable, a Civil War veteran and a party member, he was quickly promoted to a leadership role. My father wanted to get an education and started a college degree. I'll ran ahead and say that his dream of higher education didn't materialise – there were the communist construction projects, special commissions by the party… «Tell me, Yakov, what is more important to you – college or your party card? You need to go where the party needs you.» The construction of Khibinogorsk. Apatity. Then came the Finnish War. And WWII was drawing near at full speed already. The trumpet kept calling. And then even the trumpet could no longer be heard. In its place came the roar of guns, explosions and friends dying; the everyday military labour that could end only in an early grave or the longawaited victory. But that was later. For now there was the dawn of the young Soviet regime, a happy time for a Jewish lad of modest origins. The fact that a host of atrocities had already been committed by that time, while many poisonous vipers were fighting under the carpet,[2 - Cf. the remark that Russian politics resembles «dogs fighting under a carpet», attributed to Winston Churchill.] that the founders of the «radiant future» were embroiled in a long straggle to get even with each other, that by that moment the dark Eastern genius of the Kremlin had emerged fully-fledged and shown his insidious power… All this was so far away, so entirely incomprehensible to those who were the green shoots of the new Soviet land. The young vydvizhentsy did not reflect on all this; they neither saw nor understood. For them everything was simple. There it was, the bubbling, young ordinary life, so open, so naive, so selfless and honest. Work and turn the fairy tale into a true story. All paths are open to you. You are young and strong. Everything you do will turn out well. A wonderful young country. «We were born…»[3 - The first words of the official hymn of the Soviet Air Force: «We were born to turn the fairy take into a true story, to overcome space and expanse».] What remained behind were years of destitution, humiliation, the Jewish pale. National inequality. Now there was no oppression. No religions. No nations. We are Soviet people. The party leads us, and Stalin is its leader. He is just like us. Simple and easy to understand. But also wise and far-sighted. Do we now have the right to judge those who were young, ardent, genuine, naive and inexperienced then? How many people in the West were taken with the new Russian idea of universal brotherhood! There it was – the city of the sun, about to be built. The Comintern (the Third International). Everybody was waiting for the worldwide proletarian revolution. The communist idea was popular all over the world. Take the French communist and writer Vaillant-Couturier. Or Henri Barbusse, who wrote «Joseph Stalin». «He was a genuine leader, a man whom the workers discussed, smiling with joy at the fact that he was both their comrade and their teacher; he was the father and older brother, really watching over all of us. You didn't know him but he knew you; he was thinking about you. No matter who you were, you were in need of precisely such a friend. And no matter who you are, the best elements of your fate were in the hands of this other person, who was also keeping watch on behalf of everybody, working; this man with the head of a scholar, the face of a worker and the clothes of a simple soldier.» When Henri Barbusse, the French writer, journalist and public figure, the laureate of the prestigious French Prix Goncourt, sang the praises of the Great Stalin, he wrote from the heart, wrote what he was thinking. So what do we expect of our inexperienced, simple-minded fathers?

The New Economic Policy and Khibinogorsk

My mother is from Odessa. My maternal grandfather was a huge, pure-bred, handsome blond man. His surname was Koch, let's face it, not a popular name during the war. Running ahead, I'll tell you that my mother didn't change her surname when she got married and that, as it turned out, hadn't been the best of decisions. There were three daughters and one son in the family. The children were well dressed, the girls all in ruches. My grandmother was a real character, the pillar of the household. There was nothing Jewish about that family apart from its origin. Neither language nor religion. I don't know why. Everybody spoke wonderful Russian, not even a Ukrainian accent. I can't tell you the reason for that either. My mother, Lyuba, was the middle daughter. The most accomplished one. The one everybody loved best was Galya, the youngest, who was considered the most beautiful. When I began to understand certain things, this didn't seem obvious to me at all – my mother is significantly more interesting than Galya, perhaps because her entire character was more animated. The oldest daughter, Dora, who was also the oldest child, was, naturally, the first one, and was loved out of habit and inertia. Dora was unlucky; she was pitied, watched over and protected. Semyon, the son, my uncle, was tall as his father, clumsy, bashful, with no real predisposition for any one thing, although he was a good student and the only one in our family to gain a degree in engineering. Nobody paid attention to my mother in her father's house – she was clever, joyful, resilient, independent, lively, sociable, balanced, pretty, she would make her way regardless. During the evacuation in the war, when my grandfather was gone already… The husbands of her daughters were at the front. My grandmother remained behind with three daughters and three grandchildren… Everything fell onto her shoulders, which were no longer young. Grandmother suffered from high blood pressure; the high mountains of the Urals were not for her. Poor grandmother. In the evening the whole family was sitting at the table, she was laughing, joking… and suddenly it all came to an end in front of her daughters. Life was cut short in flight. Her speech faltered, she only managed to say one thing: «Lyuba, look after Dora and Galya.» And then she was gone. She had managed to say the most important thing. She knew that she could count on Lyuba for anything. But that will come later. For the time being all was well in the family of my grandparents. The children were going to school. The country was ruled by the New Economic Policy – NEP Grandfather had his own «business». A tragic story that is comic at the same time. Grandfather's business partner was a sprightly young lad. He used to come to the house frequently, spending time in the company of the three marriageable young ladies. Perhaps they weren't the most beautiful, but they were pure, neat and intelligent. A real pleasure. He managed to turn the oldest girl's head, promising to marry her and seducing her on the sly. Then he took the cash register and that was the last we saw of him. Gone. The oldest daughter in tears and with a broken heart. The business bust. The disgrace to be seen by the whole of Odessa. Perhaps for this reason, perhaps for another, the family scraped together the last of their money and left for Petrograd. That was the script of providence. At first they lived in a communal flat on Mokhovaya Street, then on the Old Nevsky Prospekt. How they made ends meet is hard to say. The children were grown, the daughters were going to school, the son was working already. The inconsolable girl who'd been «jilted and abandoned» was married off upon arrival. The parents found an unprepossessing Jew, kindhearted, plump and no longer young. He had an amazing instinct for business, a characteristic that is common among the people of the Book. He was the commercial director of a furniture factory and rather well-off for by the standards of those dark times. He was glad to be married. How they made Dora agree I don't know. Perhaps she understood that such a marriage was necessary in order to solve the family's financial problems. She never looked happy. I never saw her smile. But she was a good wife. She was faithful and maintained her family as best she could. The daughter she had was the first granddaughter in a large family and everyone's darling. But with her husband she was strict. This tradition to keep one's husband under the thumb was subsequently passed down to every single woman in Auntie Dora's lineage.

My grandfather was soon arrested by the secret police. They were arresting all the NEP-men and confiscating their gold. And he, the unsuccessful NEP-man, was arrested, too. He, the NEP-man who had had his «business» stolen, together with his money and the honour of his elder daughter. What did that matter to those guys? Give it to us here and now! Not long ago I visited the Solovetsky Islands. I walked around and thought about where my grandfather might have been. Where was he locked up, in which building? My mother abandoned her studies. She made the rounds of the official channels, travelling to Odessa and, for some reason, to Rostov-on-the-Don. She collected many certificates, went to different offices, trying to prove that they had ceased being bourgeois NEP-men long ago and were now honest members of the working class. I don't know whether it was her efforts that did it or whether the screws at that point still hadn't totally lost their mind from the smell of blood. Anyway, my grandfather returned home. Why did they forgive him, why did they leave him alive? Perhaps the screws had made a mistake. I know that many screws of the first wave were shot on the Solovetsky Islands. Perhaps because they sometimes released somebody's grandmothers and – fathers. Without conforming to the important principles of supreme proletarian justice.

However, the good times didn't last long in the old communal flat on Nevsky Prospekt. The problem was that my grandfather had been repeatedly put through the «steam room» when he was on the Solovetsky Islands. Narrow benches were placed into a small room and the prisoners were made to sit astride these benches, very close together, belly to back. Then they'd fill the room with steam. To make the prisoners suffer. To make them realise that they had to surrender what they had unrighteously amassed to the country of the working people. My grandfather returned from the Solovetsky Islands suffering from severe asthma. He died shortly afterwards.

My mother was the next candidate for marriage. We've kept a portrait of hers, drawn in red sangina pencil by an unnamed suitor who had made, as they say, a spectacular career. In the family album there is the portrait of an elegant man with a violin, who apparently had also shown interest in my dear mother before she got married. But for some reason she married my father. He was of very modest means, not very educated, not at all handsome and eight years her senior. Perhaps my mother, wise even in her youth and frightened by the unpredictable turns and harsh reality of the dictatorship of the proletariat, consciously chose a successful and, in those years, fairly influential Soviet riser-through-the-ranks. Or perhaps she had discerned his generous nature, the strength and courage of his character, and his particular masculine type. It's hard for me to tell. The photographs from this time, taken when I wasn't yet born, during my parents' holidays in the Crimea, in the Caucasus, among the snowdrifts of Khibinogorsk where my father was sent on party orders, show an absolutely happy couple. Against the backdrop of glittering snow my father, torso naked, pushes his treasure in a huge wheelbarrow – my mother, clad in a thin crepe-de-chine dress. Life was smiling at them. This was a couple, a family, a union of two complex individuals who faced a very difficult fate. Their relationship, open, kind, selfless and devoted during happy moments as well as life's harsh trials, has been and will remain to me the exemplary, ideal relationship between a man and a woman.

The Northern Caucasus

The Soviet regime provided many people with the opportunity to receive a previously inaccessible higher education. Samuil graduated from medical school in the 1920s and left his native Rostov-on-the-Don on an assignment to the Northern Caucasus. He worked in hospitals and sanatoriums in Sernovodsk, Zheleznovodsk, and Piatigorsk. The clan from Rostov dreamt that the boy might finally settle down and marry a nice Jewish girl. Samuil had his own ideas regarding life. Medicine came first. Medicine was his calling. Behind the plain exterior there was a strong, resolute character. He was a good doctor, organised, knowledgeable and capable of holding his own when it came to treating a patient. He had instinct and intuition. And, most importantly, he loved his patients. That's why he could intuit what they felt. That's why he became a good doctor. And an excellent administrator. He was head of several sanatoriums, one after the other. With regard to having a Jewish wife – no, please don't start. I know what these wives are like. They sleep until midday, and around 2pm they utter the first words: «Syoma, everything hurts!» Samuil loved Tonya Fedotova, who came from an educated, well-to-do intelligentsia family. Every conceivable ethnicity was mixed into this family: there were Russian roots, Terek Cossack influence, Georgian blood and possibly a drop of Turkish blood, too. Tonya was the younger of two sisters. She was not as beautiful as the elder sister, Tanya. But my god, what a woman she was. Delicate and feminine. Slim, well-proportioned, with the Madonna's sad face. Just like Vera Kholodnaya. She played the piano and sang in a quiet voice, kept a diary and wrote poetry. Syoma knew exactly what he needed from life. How could he not have fallen in love with Antonina? If there is a young man among the readers of this sketch, listen to your older comrade. If you happen to meet a woman with a quiet voice who is not talkative and modestly averts her pensive eyes, concealed behind long lashes, don't dismiss her, don't walk past this rare stroke of luck. The strongest, most faithful, selfless and fervent female natures are hiding behind such lowly beauty, such quiet charm. It is them who bestow upon their chosen one the most passionate embraces and become his faithful support for life.

Samuil and Tonya got married. Tonya bore two sons, Vova and Misha, two years apart in age. The chief doctor was a well-respected man. His family received a flat with three rooms. Samuil gave one room to a woman without a family, a fellow doctor at his sanatorium. He had decided that two rooms were enough for his family. Antonina was very hospitable. The doors were always half open. The house was furnished with ascetic simplicity: hospital bunks, a wardrobe, table and chairs. No other furniture whatsoever. In their place a piano, a splendid library and many guests. Antonina, slow by nature, would get up at six in the morning, run to the market, then cook. She managed to feed everybody. Anyone could turn to her family and ask for help. Some insolent women came regularly, asking for money. And Antonina would slip them something. When she had no money, she would give them food, milk, eggs, everything she had. She was incapable of turning anybody away. Acquaintances and others who had come to the resort but didn't know her well would stay at the house. Everybody, apart from Samuil's relations. They couldn't forgive his choice of a wife. They still refused to recognise Antonina and her children. The children hardly knew their father's relatives. However, all their life the children entertained a very close relationship with the beautiful Tanya, Auntie Tanya. I'll charge ahead and tell you that Misha told Tanya things he wouldn't have told his own mother.

The boys were taught music and drawing. They were very capable children. Their school grades were excellent, and both had a gift for the exact sciences. The elder, Volodya, played the violin. He was a fine draftsman, able to create with a single stroke, a single line, the image of a person or outline a landscape. The younger brother, Mishka, played the piano. However, the boys weren't mollycoddled or kept indoors. Let's remember the atmosphere of a warm, southern resort town – the atmosphere of perennial feast. A host of holidaymakers, visitors from the large cities. An abundance of fruit. And an abundance of temptations. Just as all other local children, the boys ran wild in the street, made friends with the people from Caucasus, went to the mountains, climbed trees and collected mulberries. They grew up real tomboys. Once they were chasing each other and Vova slammed the door in Misha's face, bam! Now his brother had a huge conk where his nose was meant to be. And so Misha went through life with a broken, squashed nose. Another time Misha was running after Vova, threatening him with a hot iron, and when he caught up with him he pressed the iron against his bottom, and so Vova was left with the imprint of the iron for life. Antonina decided to get an education and enrolled at the Medical Institute. On the very first day of her course her neighbours told her in the evening that they had seen her dear boys walk along the cornice of the fifth floor. There could be no talk of lectures or study. Oh, it seems that Tonya's dreams of a degree, her dreams to raise her boys to become musicians, writers, artists or doctors, were all in vain. These dreams weren't meant to come true. The younger, Misha, turned out particularly sprightly. He was lively, always laughing and very kind, and as a result everybody loved him, his peers as well as the adults. And whether through constant exposure to the sun or by nature, he was not just sun-bronzed, but downright black. Black like some Indians. Mishka-the-Black, his friends would call him. And that nickname stayed with him to the end of his life. Misha loved to play billiard. He reckoned that he had to know how to do all things better than the others. Sometimes, professional billiard players would come to the sanatorium. One of them became the boy's patron and trained him rather well. Before the outbreak of the war the short ten-year old boy was a very decent player already. Whenever someone came who wanted to play for money, some new artist on tour, Misha's billiard mentor would deploy his favourite trick. Not so quick, he would say. Why don't you first play the lad over there. People would quickly gather for their favourite spectacle. The «lad» would clamber onto a chair, as he couldn't reach the balls standing on the floor. And then he would tear the guest artist to shreds, to everyone's amusement. Yes, it didn't look as if Misha would become a pianist or writer. The country was troubled. Sometimes there was trouble in this god-protected house, too. The terrible year 1937 began to ramble and roar and then exploded in claps of thunder. «Oh how I want to fly away, unseen by anyone, fly off after a ray of light and not exist at all», wrote Mandel'shtam. We won't manage to fly away, Osip Emil'evich, we won't manage to hide or turn into an invisible ray. The local NKVD was given an order; they had to uncover and arrest several thousand hidden enemies of the people. A number of them were to be executed, the other part to be sent to the GULAG. Committees of three NKVD-members were formed, arrests prepared. Lists were compiled of Trotskyites, anti-party groups, kulaks, accomplices of the White Army, spies, war specialists involved in subversive acts, saboteurs, other alien elements. Let's have a heart-to-heart with them, they will confirm everything. Sernovodsk is a small town, everybody knew at whose house the black police car would call next during the night. In the chief doctor's house they were expecting visitors, too. The family was saved by the Chechens. They loved Samuil and decided to help. Old men in burkas came and sat down in the sanatorium's courtyard. «Samuil, don't go home. Stay here for a bit. We've told your family. They won't worry. We'll see what happens.» Every child in town knew about the Chechens in the sanatorium. For the NKVD this was an unexpected turn. There could be unforeseen disturbances. They'd get a rap on the knuckles in Moscow for this. To hell with that Samuil. May he live and work for the good of the proletarian state. He's a good doctor, isn't her? Well, let him work then. We'll manage without including him in our report. Perhaps it really happened like that. Perhaps the Chechens simply hid the chief doctor, his wife and children for a while. Whatever happened, the storm passed by Samuil and his family. But for how long? Hard to predict how the events would have unfolded further. A huge, cruel, merciless war appeared at the threshold, a war that jumbled everyone and everything and destroyed all plans to build a «peaceful» life in the land of the Soviets. During the war, a torrent of casualties flooded from the frontline into the North Caucasus. The sanatorium was transformed into a war hospital. Samuil, the sanatorium's chief doctor, became head of the hospital. His non-proletarian origin didn't stand in the way of his appointment.

The Great Fatherland War

I know little about my father's involvement in the Finnish war. Perhaps he fought only for a short time or not at the main stretch of the front. My father didn't talk about it much. He told something about Finnish snipers at the top of the fir trees and about how dexterous the Fins were at throwing knives. All the rest is muddled. By contrast, WWII, the Great Fatherland War, affected us to the full extent. Just before the war my parents received their own living space. As a fairly highly positioned leader, my father was assigned a flat with two rooms on Liteiny Prospekt. My mother was already pregnant with me. My father decided that a certain colleague of his, who already had a child, needed a separate flat more urgently and ceded the flat. For his own family he took a room in a communal flat, also on Liteiny Prospekt. True, there weren't many other people in that communal flat, which also consisted of two rooms. Our room was large, more than thirty square meters. On the third floor, without a lift. With a stove for heating. My parents only spent a very short time there at first. The war had broken out. My father was preparing his factory's evacuation to the Urals. He sent my grandmother's entire extended family (my aunts, their husbands and children, my uncle) to Sverdlovsk – that was the name of Ekaterinburg in Soviet Russia – and then he sent my mother with her baby bump there, too. She delivered me en route. Well, not on the train, naturally. When she went into labour she was swiftly made to disembark in the town of Galich, Kostroma region, where I came into this world in August 1941. Thus I saw the ancient town of Galich only once. In the following my mother made her own way to Sverdlovsk, with a nursing infant. The food was terrible. She would travel in a heated goods carriage. There was no opportunity to wash. The baby – that is, me – was covered in scabs. Instead of a crib I slept in a wooden trough. She was surrounded by men, soldiers, who had been sent down from the front for various reasons. The soldiers, who were occupying the upper levels of the bunks, picked out lice from under their armpits and dropped them. My mother cried. A wounded officer with heart disease, on his way to a home visit, lowered his head from the second bunk and said, «Don't cry, dear mother, when you son grows up he'll be a Hercules.» As if he'd looked into the future. He was almost right – I grew up to become a big, strong man. With time. Back then what was there was there.

When my mother rejoined my grandmother everyday life became easier, it seems. Although the issue of food remained, of course. It was the same for everyone at that time. Soon afterwards my father moved to the Urals with his family. My mother proudly presented him her cachetic, malnourished baby boy, evidently. Women always show their newborn babies to their beloved husbands in this way. And of course my parents' family joy was once again short-lived. My father, who would always give in to my mother in all matters and consider her opinion in literally all matters, became a very decisive man in those critical moments in life. He was vice director of a huge factory of defensive significance, exempt from military service due to his obligations at the factory and, at 38, was entering middle age. And he enlisted as a volunteer. As a rank-and-file soldier. He told my mother only when he was about to leave.

What do I remember from that time? Almost nothing. A dark stairwell. Some logs that had been stacked on the landing for some reason. A white cat playing among them. Looking at me. My future life, the bright bits and the troubled ones all together, were looking at me through that cat's child-like feral eyes. I remember stories. How my mother took up smoking. Makhorka, rough-cut tobacco. There was nothing else. How my grandmother died. How we waited for the rare letters from the front. How we listened to the song «Wait for Me and I Will Return», how we hoped and cried in silence. How the children greedily snapped up food when there was any in the house. How they swallowed quickly and growled, unable to wait for the next spoonful of porridge. The entire country lived like that. Some faded photographs from that time have survived. My mother, haggard and almost unrecognisable. Huge eyes, a prematurely aged face with a tortured expression. And a terrible puny creature, all skin and bones. That is me. In my eyes, the same suffering as in my mother's.

In 1944 we returned to our flat on Liteiny Prospekt. All our things and furniture had been taken away. By our neighbours from upstairs. My mother didn't argue with anyone. She started again, from scratch. Her sisters and brother came to her aid. Then the war was over. The men returned from the front. In the streets there were flowers, songs, accordion tunes. No news of my father. One joyful soldier in a shirt turned to me in the street, smiled at me and waved. I ran towards him, screaming 'Uncle Daddy!' I didn't know my own father after all. Then the news came that the units of the Second Ukrainian Regiment were still in Prague. That's where my father was. There, the war was still going on; people were dying. While here, peaceful life was beginning. Shops opened. One event that has stayed with me is the opening of a bakery on Liteiny Prospekt. I can still remember it. For some reason my strongest childhood impression was a loaf of white bread on the table. Bulka, as they call white bread in Leningrad.