По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

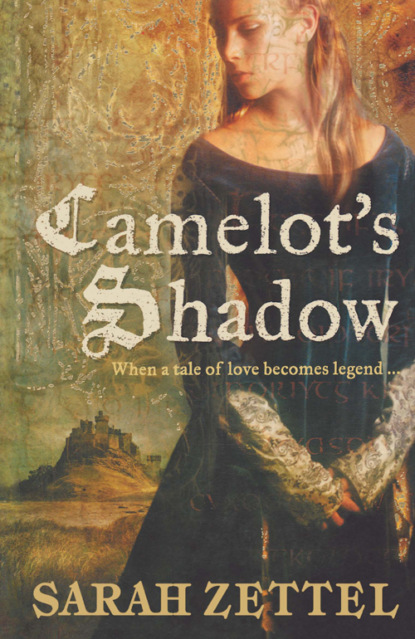

Camelot’s Shadow

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

At this, Gawain reined his palfrey back, bringing himself as close beside Thetis as the broken road permitted so that he could look her directly in the eyes. ‘Lady, you asked this morning that I speak plainly to you. Grant me the courtesy of doing the same for me. We are not, after all, in your father’s hall, nor my uncle’s. Out here, I am only a knight errant and you are the daughter of a liegeman. Shall we then be Gawain and Rhian, you and I?’

Rhian felt her tongue freeze to the roof of her mouth. It was too presumptuous. She was not sure she could do such a thing. Yet, at the same time, she longed to.

Mother Mary, I’m becoming a stuttering fool. ‘I will try.’

‘I can ask for nothing better.’ He was smiling again, that smile that lit and filled the world and suffocated sense and senses. Part of Rhian knew she had better take hold of those same senses, or she was in severe danger of making far worse than a fool out of herself, be this man ever so refined and politic in his manner. Part of her did not care and only wanted to see him smile again. During the few heartbeats she was basking in the light of that smile, she no longer had to be afraid of what followed her, and she felt no nightmares resting on her shoulders. She greatly yearned for that relief.

‘So, Rhian,’ he stressed her name and the smile flickered about his lips as he did so. ‘If you will not tell me your thoughts, what shall we talk about instead?’

Curiosity itched at Rhian’s mind, and she decided to dare his disapproval. ‘Can mmm…’ deeply ingrained habit made her tongue stumble. ‘…you tell me what brought you to the borders of my father’s land?’

Gawain looked at her carefully, weighing and judging some quality Rhian could not guess at, and he made his decision. ‘The Saxons plan to start the wars again,’ he said. ‘I am carrying that warning to the High King.’

His words at once dropped fear into Rhian’s heart, making it beat slow and heavy and filling her with the sharp and sudden longing for the stone walls of her father’s hall. All her life, she had heard tales of the Saxon invaders, of the raids and rapes, sackings and burnings. She had also heard, and told, how High King Arthur had broken the invading forces, sending them scurrying back to Gaul, or leaving them clinging to the eastern coasts muttering to themselves in their dark fortresses behind wicker fences.

That they would come again…that they would be here…In the light of day it was comparatively easy to shake off the immediacy of magic and sorcerers, but the spear, the knife and the torch – those were far more solid things. In an instant, the trees were once again the home of terrors, and Rhian had to swallow hard against her fears.

‘How close are they?’ the words came before she had time to worry about discretion.

‘Two days’ ride.’ Gawain looked to the distance. They had topped the rise and ahead the wood seemed to be thinning, but Rhian was no longer sure of her bearings, though Gawain seemed to be. How much time has been lost already? she could practically hear him thinking.

Rhian bit her lip. ‘Is there any way to get word to my father? He should know.’

Gawain looked genuinely shocked. ‘After what he has done to you, you would care?’

‘Does my mother deserve to suffer for what my father has done?’ snapped Rhian. ‘The men and women of our holding?’

Gawain looked quickly away. ‘Forgive me, that was an unworthy thing that I said.’ The apology was smooth and courtly, as perfect as all his other manners, but there was something more underneath it, a trace of some old wound or faded nightmare of a memory. Whatever it was, Gawain shook it quickly off. ‘It would not do to let the invaders know yet that we have word of their plans. As soon as I have taken counsel with the king, I am certain he will send out messengers to his liegemen to stand in readiness.’

But will that be soon enough? It was all Rhian could do not to look back down the twilit road again.

‘I do not seem to be succeeding in reassuring you, Lady Rhian,’ Gawain said wryly.

It was indeed lighter ahead. She should concentrate on that, see it as a sign, behave properly and forget her curiosity. ‘If I want reassurance, perhaps I should simply stop asking questions.’

‘I think that such silence would ill become you.’ Was he simply being polite once more, or did he truly mean that? His face had softened, particularly around his eyes. ‘It might make the road more smooth.’

That brought him out of reverie into philosophy. ‘And where is the glory in the smooth road?’

I wonder, Sir, if you’ve forgotten who you are speaking with. ‘I have been told glory is not for ladies.’

‘I know of at least one lady who would argue that point.’ Gawain’s eyes took on a knowing glint.

Rhian drew her shoulders back and set her face in a fussy imitation of Aeldra. ‘What lady might this be to say such an unladylike thing?’

‘The High Queen, Guinevere,’ replied Gawain matter-of-factly.

Rhian found she was not ready for that answer. She concentrated on keeping seat and hands steady while Thetis picked her careful way down the slope between the stones, gouges and damp drifts of leaves. The day had warmed and clouds of midges swarmed around Thetis’s ears. Perspiration prickled Rhian’s scalp under her veil and the lack of food was beginning to have an effect on her. She wondered if Gawain had any bread in his bags that they might stop and share. The last swallow of watered wine seemed a long time ago.

‘What is she like, Queen Guinevere?’ she asked instead, not wanting to complain or slow their progress. ‘I have never been to court.’

Gawain smiled then, and for a single heartbeat, Rhian thought he looked more like a man thinking of his lady-love than one thinking of his aunt. But as he spoke, she told herself firmly that she was most mistaken.

‘A more loyal and virtuous lady is not to be found. She is wise in her counsel both public and private, and generous to those in need. Her appearance is noble in all aspects, and her grey eyes are justly famous.’

Grey-eyed Guinevere, she

who rode at the king’s left hand

the fairest flower of womanhood

e’er seen in Christom’s vasty lands.

The words rang unbidden through Rhian’s memory. She wondered if Gawain knew that particular poem. He certainly seemed ready to confirm its praises. She should have felt reassured by this. She was certainly in need, and she could think of nothing she had done to deserve what she had come to, but she could not bring herself to take heart.

‘She is learned, as well,’ Gawain was saying, warming to his theme. ‘Schooled in Greek and Latin, and familiar with poets and writings in both languages. She is perfectly matched with her husband in this respect. Arthur seeks to rule with learning and follow the Roman traditions of laws and letters. It is a good way. It is a better way…’ but his words trailed off and all at once, the road ahead seemed to take all his concentration. They had come to level ground again, and the trees here were younger and thinner. Patches of meadow grass sprang up between the gnarled trunks and the bird calls grew softer and at last, they broke the treeline, emerging, blinking into the sunlight of a marshy meadow land dotted with white and yellow flowers and smelling of damp grass and warmth.

Rhian opened her mouth to ask Gawain to continue, but then he reined his palfrey back, causing Gringolet to check his step. Rhian pulled Thetis up as well, and she followed Gawain’s gaze. Ahead, where the trees began again, there rose a thick column of dark smoke, dispersing to a black mist on the faint breeze.

‘What is it?’ she asked, seeing how Gawain’s face had grown suddenly grave.

‘That smoke is too heavy for a camp or a charcoal burner,’ he said. The palfrey danced impatiently under him, and Gawain patted it automatically, but he did not look away from the smoke. ‘There is no village or town in that direction. I do not like it.’

Without another word, Gawain urged the palfrey forward, leaving the road for the muddy meadow and taking his direction from the smoke plume. Gringolet lifted his hooves high and fastidiously to follow. Rhian and Thetis had little choice but to do the same.

The trees soon closed in around them once more, making it impossible to ride, and they both dismounted to lead their horses, pushing aside whip-like branches and directing their paths around decaying logs and pools of standing water. Rhian could not see the smoke now, but she could smell it, strong and acrid, and wrong somehow. It did not smell like a friendly hearthfire, nor did it carry the tang of the forge or the kiln. The birds overhead had all gone silent, and the only noise was the squelch and crackle of their passage.

No. Something else.

Rhian strained her ears, and heard a vague and distant crackling noise that should have been familiar, but that she could not make her mind identify.

They came to a narrow and rutted track, an offshoot of the main road, so little used that the forest plants were already beginning to sprout along its length. Gawain held up his hand, signalling her to halt. The scent of smoke had grown stronger, and the crackling, Rhian realized, must be the sound of the fire that made that smoke.

Gawain peered through the trees across the track. Rhian could see little through the greening branches, only some dark shapes that could have been anything from standing stones to an overgrown Roman fortress.

‘Wait with the horses, lady.’ Gawain did not look back at her as he spoke. He did, however, loosen his sword in its sheath.

With the smell of smoke and the sound of fire in the wind, and the knowledge that the Saxons were planning to begin their wars once again. Rhian did not want to walk forward to find out what was burned in these woods, but neither did she want to stand here alone.

She covered her fear in bravado. ‘You urge me to follow the example of Queen Guinevere. Would she remain behind at such a time?’

He turned to stare at her. She made herself look determined, although inside she was beginning to feel ill.

But her countenance must have been strong enough. ‘Agravain is ever reminding me to guard my tongue more closely,’ Gawain muttered. ‘Did you bring a spare bowstring?’

‘I did.’

‘Then restring your bow, Lady Rhian, and come.’