По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

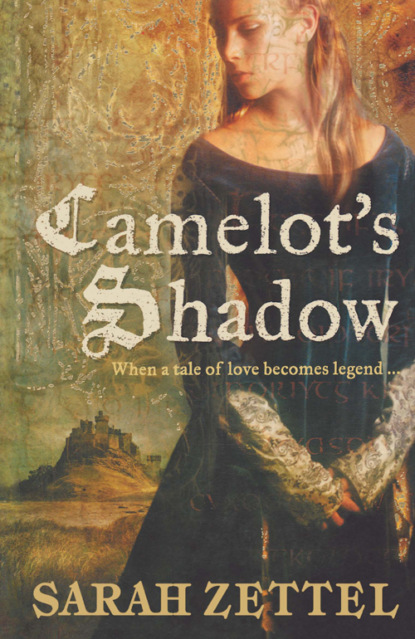

Camelot’s Shadow

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

At first, Kerra tried to block out the dreams. She prayed herself to sleep and made herself a cross to clutch through the night. But gradually, she began to listen to the dream woman. No one else had ever said they could help. The midwives and cunning men mother consulted had done little more than shake their heads. The priests had laid their hands on her head and raised their eyes to Heaven, and nothing had changed. This woman swore she could help, and all she wanted in return was a healer. Her infant son was ill with a fever in his lungs, she said. The sickness had spread to her. She was weak. He was dying. If Kerra helped them, saved their lives as her mother surely would had she but known, then Kerra would be taught to control the power that was within her.

Kerra could not long resist such a promise. It was harvest time. They were staying with a cluster of fishers on the ocean shore who agreed mother’s ‘half-wit’ daughter could stay in the drying shed as long as mother played midwife for the two bearing women and healer for the men who worked with lines and nets.

At the dark of the moon, Kerra crept from her warm, stinking shelter and fled inland to where the woods began. There she found the woman who named herself Morgaine and the infant boy, her son, saved from drowning she said. His lungs were bad, and his fever was high, and his mother had little milk to give him. Kerra built them a shelter of branches such as she and her mother used when they were on the road. She brought them goat’s milk, and fish and mussels she searched out from the tide pools. She brewed them strong teas using her mother’s recipes and herbs she had filched from her mother’s bags or ferreted out from the woods.

Slowly, the babe improved. His cough subsided and his limbs grew round and strong again. When it became clear that he would live, Morgaine began to keep her promise to Kerra.

Kerra, Morgaine said, was not cursed, but blessed. It was only because she was untutored that her natural powers threatened to run wild. She taught Kerra the rites that would summon the voices and the visions, and send them peaceably away. Her fits faded away to memory and all her dreams were of the normal kind. She learned how to call the ravens to her as friends, and how to work with bone and poison to achieve her ends when the healer’s art was of no use. She learned the names of the powers that inhabited land and sea, their natures and which were to be avoided and which might be plied or pressed into service.

In time, she also learned manners, dress and bearing. She learned the ways of men and women and how they might be enhanced with her other arts. To all these studies and many more she applied herself willingly, until the day came when it was she who walked away. Leaving her mother to her roving, Kerra set herself firmly and finally to Morgaine’s campaign against the king in Camelot and his helpmeet and fellow conspirator, Guinevere.

The voices of her companions roused Kerra from her bitter reveries. Their thoughts pushed against hers. They did not like this place. They wanted her to come with them, to fly, and to sport on the winds.

Kerra smiled at the great flock gathered around her.

‘Yes, my friends,’ she said. ‘Yes, we will fly.’

Kerra retrieved her sewing basket. From under the meaningless pieces of fine work, she drew out a great black cloak. The basket itself was far too small to conceal such an object, but it came to her hand nonetheless. She shook it and the sunlight glinted on the rich black feathers borrowed from one thousand living ravens. Kerra settled the cloak over her shoulders, closed the bone clasp, drew the hood up over her hair and steeled herself against the pain.

Kerra’s bones began to shrink. Her legs lengthened and her joints buckled, feet and toes split and splayed. Her body solidified and her neck thickened even as her face lengthened and bone split skin to form a sharp, black beak. Feathers sprouted from every pore and from the tip of each finger as her arms reshaped themselves to become her wings and all around her the ravens voiced their approval.

Then, one bird among many, she took to the air, beating her wings joyfully until she was able to catch the wind and soar with the rest of the flock over the tops of the trees and away out into the countryside.

As Euberacon watched, the ravens one by one left their perches on the roof and in the trees beyond the fortress walls, joining Kerra in her eyrie.

He knew she had her own plans that she kept carefully hidden from him. She thought she was using him, just as she thought it was his carelessness that led Gawain to take Rhian from him. She was wrong, but that did not mean she should not be treated with great caution. Even a barbarian could be dangerous. The pike and the axe could kill as thoroughly as the sword. It was as well to trust her no farther than absolutely necessary, and when he left these shores for Byzantium, it would be wise not to leave her alive.

For now, though, she was most useful. She would lay the traps that would drive Gawain and the girl apart. Her mischiefs would bedevil them and make peace of mind a stranger. It was likely she would fail, but the attempt would have the effect of making them cling more closely to each other, and that closeness would breed the weakness he needed for his own work.

Euberacon crossed his beautiful courtyard, returning to his tower and his carefully laid plans.

FIVE (#ulink_1c2d3bd7-e953-5288-a669-c57f5d9b1a39)

The day was clear as crystal and at least as cold. Rhian was glad Sir Gawain kept the pace brisk, for although the wind stung her cheeks, Thetis’s motion helped keep her warm and distracted her somewhat from the lack of food.

And she needed every distraction she could get. They were still in the wooded country, with the great trees gathering close to the road, waving their branches in salute to the morning’s wind. This was not a well-travelled section of the road, and the ruts and holes had become puddles the size of young lakes. Twice they had to dismount and lead the horses through the trees to avoid burgeoning bogs. Sunlight and shadow shifted, spread and scattered like foam on the sea. The world filled with the rush and creak of the trees’ song, a constant accompaniment to the calls of birds and the hundred nameless noises of the newly wakened forest dwellers, all of them seeking shelter somewhere away from the disturbance made by three horses and two human beings. It took all Rhian’s strength to keep from starting at shadows ahead that might be a dark man with heavy-lidded eyes, or from turning constantly to see behind. Were the only hoofbeats she heard truly from the three horses of their party? Or were there others? Their tracks were plain in the mud and the soft earth along many long stretches where the stones the Romans had laid down were broken and gone. Anyone, certainly any of father’s men, would only have to look to know where they had passed. How much more would a sorcerer be able to do?

It did not help at all that the words from one dark ballad had begun to beat their time through her mind again and again and would not be shifted.

‘Light down, light down, Lady Isobel,’ said he,

‘For we are come to the place where you are to die.’

That all ended well enough for the lady in that tale gave her no comfort. Her mind could not reach that far.

For we are come to the place where you are to die.

‘I see my lady favours a bow.’

Rhian nearly jumped out of her skin. Thetis whickered and broke stride. Rhian had to pat the horse’s neck and prod her to continue before she could look up at Gawain, whose face was all casual inquiry.

‘I do, yes,’ she answered, trying to warm to the idea of polite conversation. What was that in the trees? Was it only a bird?

‘Do you hunt?’ he went on.

‘When I can.’ How many sets of hooves drummed on the road? Mud muffled and confused sound, turning steady drumming into wet and uneven plodding. The way ahead rose steeply. They were leaving the lowlands for the hills, with their dells and valleys and deep folds in the land, where anyone might conceal themselves. She could see next to nothing. She could not hear properly.

‘Lady Rhian.’

Again, Rhian jumped. Again Thetis complained of it and had to be soothed. When she was able to look up at Gawain, his fine face was all sympathy.

‘Take heart, Lady Rhian,’ he said. ‘We are alone on this road.’

Rhian dropped her gaze. ‘I know it, Sir,’ she said. ‘It’s just that…if I…if…’

At her stammering, Gawain gave a small smile and Rhian felt a blush blossom across her entire face. ‘Lady Rhian,’ he said again, as gently as he had before. ‘Last night I said you were under my protection. I will not permit any harm to come to you. If an oath is necessary to make you believe this, then I swear it.’

‘Sir, please believe that I do not doubt your word. But if my father…’

‘Your father is the king’s man and needs must obey the king’s word. Until the king himself appears, that word comes from me, and I say you are going to Camelot.’

Rhian looked away, trying not to scan the budding underbrush for movement. ‘Would ‘twer that simple.’

‘It is that simple, Lady Rhian. It is law.’

He spoke the words so plainly. Did he not understand? Churlishness rose in Rhian and would not be dismissed. Before she could guard her tongue she said, ‘You have slain dragons, my lord. The rest of us know rather less of such legendary battles.’

Sir Gawain stared at her blankly for a moment. ‘God in Heaven,’ he said at last. ‘Is that what they say of me now?’

‘Every year at the feast of Christ’s Mass.’ I’ve told it myself, she added in her mind, but decided not say so aloud.

A spasm crossed the knight’s face, as if he was not certain whether he wished to laugh or curse.

Laughter won out. ‘Well then, my lady, if you can believe I have slain dragons, it should be a matter of no moment to believe I can stand up to your father!’

Much to her surprise, an answering laugh bubbled out of Rhian. It felt surprisingly fine, like a spring morning, and Gawain’s smile had returned in truth, turning his face again to that picture of a man’s beauty she had seen so briefly before, even with the dark stubble dusting his chin.

After a moment, his face grew thoughtful again, studying hers. Rhian fixed her gaze on the rising narrow way ahead, on the shifting patterns of light and shadow from the branches waving in the spring wind. Thetis did not like uneven ground and was growing nervy, so that Rhian had to concentrate on keeping her seat and on guiding her mare, which was just as well. She needed to think of something else but Sir Gawain’s eyes studying her so closely.

‘It is good to see you smile, Lady Rhian.’

It is good to believe I will smile again, thought Rhian, but that was hardly a thing she could say to this man. She concentrated instead on keeping the reins loose in her fingers. It would not do to have Thetis betraying her moods.

Perhaps in my next flight into the wilderness I should go on foot.

Gawain was not content to let her keep her peace, however. ‘May I ask your thought?’

‘Oh, it is nothing of importance, Sir.’