По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

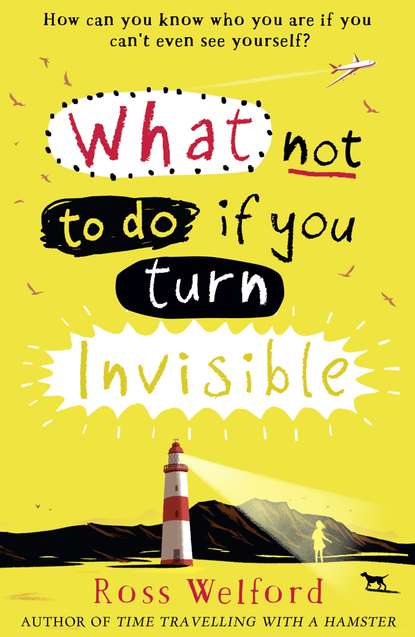

What Not to Do If You Turn Invisible

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

I had no idea what it was all about. None at all. Tiger? Had she said ‘pussycat’? Or something else? Thing is, Great-gran is a hundred and not everything works like it should, but she’s not actually senile.

She turned her head to Gram. Her eyes still hadn’t lost their intensity and, for just a moment, it was like looking at a person half her age.

‘Thirteen,’ she repeated. There was something about all this that I wasn’t getting, but I’d have let it all go if Gram hadn’t suddenly come over all brisk and matter-of-fact.

‘Yes, isn’t she growing up fast, Mum?’ said Gram with a little forced laugh. ‘How quickly it all happens, eh? Goodness, look at the time! We’d better get into the sitting room. People will be waiting.’

AN ADMISSION

So there’s another problem with visiting Great-gran, even on a happy occasion like a birthday. Old people make me sad.

It’s like: I’m starting to grow up, but they finished all that ages ago and they’re growing down. Everything is done for them, to them, and they don’t really get to decide anything, just like little children.

There’s a man who is very old and very deaf, and the staff have to shout to make themselves heard. So much so that everyone else can hear as well, which is sort of funny and sort of not.

‘EEH, STANLEY! I SEE YOU’VE HAD A BOWEL MOVEMENT THIS MORNING!’ bellowed one of the nurses once. ‘THAT’S GOOD! YOU’VE BIN WAITIN’ ALL WEEK FOR THAT, HAVEN’T YOU?’

Poor old Stanley. He smiled at me when I went past his room; the door is always open. (Most of the doors are open in fact, and you can’t help looking in. It’s a bit like being in an overheated zoo.) When he smiled he suddenly looked about seventy years younger, and it made me smile too, but then I felt sad and guilty all over again, because why should it make me happy that he looked young?

What’s wrong with being old?

(#ulink_0cf0eb9b-af32-5142-bee2-e4c2308a07b9)

Great-gran was wheeled out of her room by one of the staff, Gram scuttling behind her, and I was left alone, staring at the sea.

There was something missing. Someone missing.

My mum. She should have been there. Four generations of women in the family and one of them – my mum – was being forgotten.

How much do you remember from when you were very little? Like, before you were, say, four years old?

Gram says she hardly remembers anything.

I think of it like this: your memory is like a big jug that gets gradually fuller and fuller. By the time you’re Gram’s age your memory’s pretty much full, so you have to start getting rid of stuff to create room and the easiest stuff to get rid of is the oldest.

For me, though, the memories I have of when I was tiny are all I have left of my mum. Plus a little collection of mementos, which is really just a cardboard box with a lid.

The main thing in it is a T-shirt. That’s what I always see when I open the box up because it’s the biggest item. A plain black T-shirt. It was Mum’s and smells of her, still.

And when I open the box, which stays in my cupboard most of the time, I take out the T-shirt and hold it to my nose, and I close my eyes. I try to remember Mum, and I try not to be sad.

The smell, like the memory, is really faint now. It’s a mixture of a musky perfume and laundry detergent and sweat, but clean sweat – not the sort of cheesy smell that people say Elliot Boyd has but that I’ve never smelt. It’s just the smell of a person. My person, my mum. It’s strongest under the arms of the T-shirt, which sounds gross but it isn’t. One day, the smell will be gone completely. That scares me a bit.

There’s also a birthday card to me, and I know the rhyme off by heart.

To a darling little person

This card has come to say

That I wish you joy and happiness

On your very first birthday

And in neat, round letters it’s handwritten: To my Boo, happy first birthday from Mummy xoxox

Boo was Mum’s pet name for me. Gram said she didn’t want to use it herself because it was special to me and Mum, and that’s cool. It’s like we have a secret, me and Mum, a thing we share, only us.

The nice thing about the card is that it has picked up the tiniest bit of the T-shirt’s smell, so as well as smelling of paper it, too, smells of Mum.

I was thinking about this, sitting in Great-gran’s room, when Gram interrupted my thoughts.

‘Are you coming, Ethel, or are you going to daydream? And why the long face? It’s a party!’

I’ll skip through it quickly because it was about as exciting as you would expect … apart from another weird thing that happened towards the end.

GREAT-GRAN’S PARTY

Guests:

About twenty people. Apart from me and a care assistant called Chastity, everyone else was properly grown up or ancient.

What I wore:

A lilac dress with flowers on it with a matching Alice band. Gram thought I looked lovely. I didn’t. Girls who look like me should just be allowed to wear jeans and T-shirts until the whole gawky-skinny-spotty thing runs itself out. As it is, I looked like a cartoon version of an ugly girl in a pretty dress.

What I said:

‘Hello, thank you for coming … Yes, I’m nearly thirteen now … No, I haven’t decided my GCSEs yet … No, [shy, fake grin] no boyfriend yet …’ (Can I just say at this point: why do old people think they can quiz you about boyfriends and stuff? Is it some right you acquire as soon as you hit seventy?)

What I did:

I handed round food. Gram had asked me what she should serve, but my suggestion of Jelly Bellys and Doritos had been ignored. Instead there were olives, bits of bacon wrapped round prunes (yuk – whose idea was that?), and teeny-tiny cucumber sandwiches. The chances of me sneaking much of this into my own mouth were slim to zero.

What Great-gran did:

She sat in the centre of the room, smiling a bit vacantly and nodding as people came up to her and congratulated her. I was thinking she was not ‘all there’, not aware of what was going on. As it turned out, I was wrong about that.

The photograph:

A photographer from the Whitley News Guardian took a picture of me and Gram and Great-gran next to a large cake. He had a tiny digital camera instead of a big one with a flash that goes whumph! I was a bit disappointed: like, if you’re going to be in the local newspaper, it should feel dramatic, like a special moment, you know? (Irony alert: as it happens, that photograph is going to turn out to have very dramatic consequences.

(#ulink_bf8d8fd6-168a-53ef-822f-7a98a19daeb0)

Anyway, Mrs Abercrombie was at the party with Geoffrey, her three-legged Yorkshire terrier, who was doing his bad-tempered snarly-gnarly thing – and I have a new theory about this. I think the reason he’s so snappy is because she never lets him run around. She is forever holding him in one arm. I’d be annoyed if I was forever pressed into Mrs Abercrombie’s enormous chest.

Gram looked nice. ‘A veritable picture’, as Revd Henry Robinson said.

She sipped from a glass of fizzy water and smiled gently whenever people spoke to her, which is about as far as Gram’s displays of happiness go. She hardly ever laughs – ‘Ladies do not guffaw, Ethel. It’s bad enough in a man. In a woman it is most unseemly.’