По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

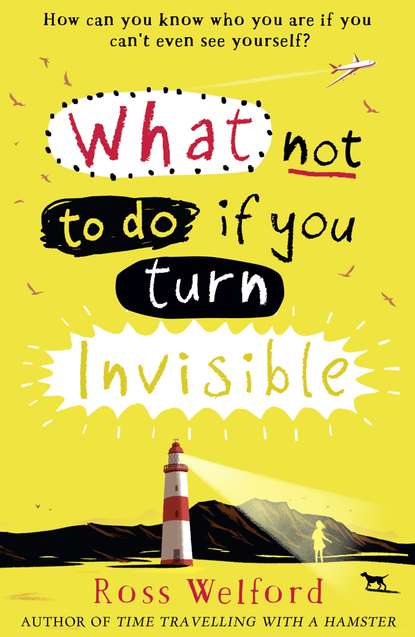

What Not to Do If You Turn Invisible

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

(#ulink_7bbf0b69-a7a6-50b7-9e6e-a1f1fb47e1f6)

That’s when I know she doesn’t believe me.

Why would she? It sounds completely demented. Gram doesn’t believe me because she cannot see me, and if she cannot see that I actually am invisible, then why on earth should she believe me?

It’s crazy. ‘Preposterous’ even, to use one of Gram’s favoured expressions.

I wait. I have told her everything. I have told her the whole truth and nothing but. All I can do is wait to see what she says.

What Gram says is this:

‘Ethel, my pet. It’s hard growing up. You’re at a very tricky crossroads in your life …’

Oo-kaay, I think. Don’t like the sound of where this is going, but go on …

‘I think many of us feel invisible at some point in our lives, Ethel. As though everyone is just ignoring us. I know I did at your age. I did my best to fit in, but sometimes my best was not enough …’

This is getting worse. Can there be anything worse than a sympathetic response that completely and utterly misses the point?

I’m struck dumb, sitting there listening to Gram drone on about ‘feeling like you are invisible’ while I watch my teacup magically rise and fall to my lips.

Then I look down and gasp in horror. There’s the tea that I have just drunk, floating in a little misshapen lump where my stomach is.

My gasp causes Gram to pause.

‘What is it, darling?’

‘My … my t-tea! I can see it!’ No sooner have I said this than I realise how daft it sounds.

‘I beg your pardon, Ethel?’

‘Oh, erm … nothing. Sorry. I, erm, I missed what you were saying.’

‘Listen, I’m sorry you’re feeling this way, but we’ll have to talk about it when I get back this afternoon. It’s the treasurer’s report next and Arthur Tudgey is sick, so I have to deliver it. I have to go back in.’

And I’ve had enough. That’s it.

‘No, Gram. You’re not listening. I really have disappeared. I don’t mean in an imaginary way. I mean really. Really really – not metaphorically. My body is not visible. My face, my hair, my hands, my feet – they are actually invisible. If you could see me, well … you wouldn’t be able to see me.’

Then it hits me.

‘FaceTime! Gram, let’s FaceTime and then you’ll see!’

I’m not even sure Gram can do FaceTime, but I’m sounding hysterical anyway.

I’m trying to put this the best way I can but it’s coming out all wrong, and the tone of her voice has gone from sympathetic and concerned to something a little bit harder, a bit stern.

‘Ethel. I think you have gone far enough with this, darling. We’ll talk later. Goodbye.’

It’s me who hangs up this time.

(#ulink_7d253117-7f4c-5cf9-95cf-6e6ba69d259c)

Think back to the last time you were on your own. How alone were you really?

Was there someone fairly close by? A parent? A teacher? A friend? If you were in trouble, could you have called someone to help?

OK, so I’m not exactly Miss Popularity at school, but it’s not like people actually dislike me. Well, I don’t think so anyway.

‘There is absolutely nothing wrong with being “quiet and reserved”,’ said Gram when she read this on a school report once (and until then I had never thought there was, actually, or that anyone would think there might be).

‘Better to keep your mouth shut and be thought stupid than to open it and remove all doubt,’ she added in a typically Gram kind of way.

Gram has always been – to use a phrase she is fond of herself – ‘very proper’.

She is fond of saying that a civilised, cultured Englishwoman should know how to behave in every situation.

Honestly, she has books on stuff like this. Books with titles like Modern Manners in the Twentieth Century. They’re funny, usually, but most of them seem to have been written when Gram was alive, so they’re not that ancient. They include things like:

What is the correct form of address when meeting a divorced duchess for the first time?

Or:

How much does one leave as a tip for the household staff after staying at a friend’s country house?

If you didn’t know Gram, I daresay it could make her seem buttoned-up and strait-laced – the insistence on writing thank-you letters within three days, for example, or always asking permission before calling an adult by their first name. Actually it’s just about being polite to people and that’s quite sweet – only, Gram takes it further than anyone else I’ve ever met.

She once gave me a lesson in shaking hands.

Yes, shaking hands.

‘Eugh, dead haddock, Ethel, dead haddock!’ That was Gram’s description of a limp handshake. ‘You must grip more. Ow! Not that much! And I’m here, Ethel! Over here: look me in the face when you shake hands. And are you pleased to see me? Well, tell your face. And … what do you say?’

‘Hi?’

‘Hi? Hi? Where on earth do you think you are? California? If one is meeting for the first time, it’s “How do you do?” Now show me: a firm, brief handshake, eye contact, a smile and “How do you do?”’

(I actually tried this when I met Mr Parker for the first time. I could tell he was pleased, but also a bit, well, unnerved, like it was the first time any student had greeted him like that – which it may well have been. Mr Parker has been super-nice to me ever since, which Gram would say is proof that it works, and I think is probably just because Mr Parker quite likes me.)

So Gram is not all that old but she is old-fashioned, at least in her clothes. She’s proud of the fact that she has never owned a pair of jeans, even when she was much younger and good-looking. Her denim aversion is not a protest against the modern world, though. The reason she hates jeans is that she says they are unflattering.

‘Wear them tight and they are indecent; wear them loose and you look like some gangster rapper.’

Believe me: when my gram utters the words ‘gangster rapper’, it’s like she’s practising a foreign language. You can hear the quote marks round it.

Being able to talk to anyone, from any walk of life, is a great skill if you’ve got it, but even if I did, it would be no help to me right now. There is no one I can talk to about this whole invisibility thing.

Gram? Tried that.